A person in a grey shirt looks out from a balcony

After leading my students, all high school seniors, on a field trip to a local domestic violence (DV) organization to get a better understanding of intimate partner violence (IPV), I didn’t expect to be the one to leave with an epiphany.

On the bus ride back to school, I messaged my ex who had been with me through many of those thrashing years of high school and college: “Whenever I hear about methods of control in DV situations, I hear echoes of a younger, way-more-insecure me. I am so sorry you had to deal with that me. Sorry also that it has taken this many years to apologize.”

She was “floored.” I responded that I hoped that the floor was clean. My past certainly has not been. What’s more, I spent much of my life never fully understanding how dirty I was.

Long before I joined Everyday Feminism, I joined Facebook and began reconnecting with childhood folks who knew that younger me. One woman, who I had never been particularly nice to in my adolescence, praised an article I wrote on male privilege and asked how I “started to get it.”

Though she didn’t say it like this, the question I heard, knowing my history, was: How did you go from being such an asshole to a writer for Everyday Feminism?

A fair question, one I more than earned.

But it’s a complicated question. First, I’m still a bit of an asshole, though I make a conscious effort to keep any assholery separate from systems of oppression. Second, I have editors telling me this piece is supposed to be an article, not a memoir.

But the article-length answer is that, over the course of my life, I have found numerous frameworks to help me makes sense of my behaviors – and unlearn them, or at least try to.

Let’s start with what I learned from working with DV organizations:

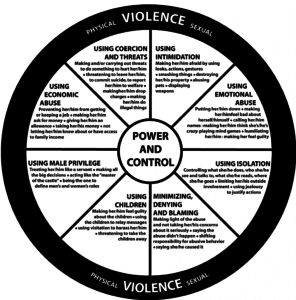

1. The Power and Control Wheel

Because most cis, straight men like myself don’t formally study issues of gender, when we think of intimate partner violence, we usually think of illegal acts – physical and sexual violence. Many DV organizations refute these misconceptions using the Power and Control Wheel.

For example, during the years with my ex, when I was feeling particularly hurt or vulnerable, it was not uncommon to unleash a fury of punching directed at the nearest wall, windshield, or sometimes myself – leaving me with dents in bedroom walls, cracked skin and windshields, headaches – and a very scared partner.

When I discuss the Power and Control Wheel with my students, they confirm that such behaviors are alarmingly common.

A therapist I once worked with – one whom I sought out because of my inability to access my emotions – taught me that those fits were a consequence of masculinity. My emotions would spill out as rage because I, as a cis man, was trained to suppress them until they consumed me.

According to her, I was a victim of masculinity. Liking that narrative, I wrote that interpretation in ink for many years.

I now interpret those fits of rage as a means of control, a textbook case of “Using Intimidation” on the Wheel. If my partner answered a loaded question with the answer that hurt me, she risked a punching storm. It was far safer to tell me what I wanted to hear.

Other behaviors of mine that permeate the Wheel might better be described today as gaslighting, which Shea Emma Fett describes as “an attempt to overwrite another person’s reality.”

I remember on numerous occasions actually blaming my ex when men hit on her – as if I had somehow become the victim. Instead of viewing these unwelcome advances by others as harassment against her, I viewed them as threats against me that could lure away my primary source of validation – my girlfriend.

Even without the Wheel, it’s obvious how problematic these behaviors are, and I cringe rehashing them in writing. But the Wheel gave me a framework to reflect on behaviors I had not thought about in years. It spurred a wave of nostalgia – except that they were shitty memories, not sentimental ones, that rushed back into my consciousness.

2. Toxic Masculinity

Of course, I didn’t develop these behaviors in a vacuum.

I had help – like an entire society training me not just how to gain control over my partner but also that I was entitled to do so.

Poet Tony Hoagland describes some of this training in “The Replacement”:

It is a kind of cooking

the male child undergoes:

to toughen him, he is dipped repeatedly

in insult—peckerwood, shitbag, faggot,

pussy, dicksucker—until spear points

will break against his epidermis,

until his is impossible to disappoint.

I bring up this training not to pass the buck or let me off the hook. After all, I embraced much of it. I chose to enroll in weight training classes for more aesthetic than health reasons. I chose to watch those shows full of gratuitous objectification. I chose to cannonball into the waters of superficiality.

But it’s important to more deeply understand the source of one’s actions.

Harris O’Malley defines toxic masculinity as a “narrow and repressive description of manhood, designating manhood as defined by violence, sex, status, and aggression.”

I was playing out a script of toxic masculinity that I didn’t necessarily author, and realizing this fact helped me find a new script – even if I couldn’t forget many of the lines from the old one.

Toxic masculinity is the mainstream school that too many of us attend to learn abusive behaviors. And while anyone can exhibit abusive behaviors, if we look at IPV, cis straight men are far more likely to be the perpetrators.

In response to an underreported shooting, Melissa Jeltsen writes:

According to PolitiFact, there have been 71 deaths due to extremist attacks on US soil from 2005 to 2015. Compare that to the drumbeat of women killed by their intimate partners, which number three daily. In California alone, there were 118 domestic violence-related homicides in 2015. On average, there are nearly 11 murder-suicides nationally each week. Most involve a man killing his wife or girlfriend using a gun. But they get little sustained media attention.

Recent years have been banner years for toxic masculinity, as The Representation Project recently highlighted in a three-minute video.

But the ‘70s and ‘80s contained enough toxic masculinity to require that the rest of my life be spent unlearning and deprogramming.

3. True vs. False Self

Understanding the concepts of the true and false self accelerated the deprogramming.

In my message to my ex, I mentioned that my youth had been marked by extreme insecurity. I was a skinny White kid whose only remarkable quality was how thoroughly unremarkable I was. I lived directly atop of the bell curve.

Having my love returned by a remarkable person was validating. But also problematic, as I found self-worth not from myself, which is where you’d expect to find self worth, but from my relationship.

Mary Pipher – author of Reviving Ophelia, the classic (White) feminist text from the ‘90s – frames this type of validation as symptomatic of the “false self,” which is socially scripted, most often by unhealthy sources like the market-driven media.

Pipher writes, “With the false self in charge, all validation came from outside the person. If the false self failed to gain approval, the person was devastated.”

She wrote this with adolescent girls in mind, but other a/genders can also find the framing useful. After all, we can all relate – at some level – to the pain involved when we can’t own all of our “emotions and thoughts that are not socially acceptable.”

In contrast, people honoring their “true selves” accept themselves, rather than waiting for others to accept them. Not having fully accepted myself, I drew an unhealthy amount of value from my relationship.

And if my ex had power over my self worth, I consciously and unconsciously did what I could to get control over her. And toxic masculinity normalized my behaviors so I could act without self-examination.

Exploring my true self, however, led to some really heavy questions – like who the fuck am I, really?

What truly feeds and nurtures me? The answers to those questions, for me and most folks, don’t include hurting the ones we care about. In fact, I wonder how many abusive people are abusive because they have denied themselves their true selves.

In the end, we all lose when we play out someone else’s script.

4. Good/Bad Binary

We also lose using the good/bad binary.

In my experience, the good/bad binary is a counterproductive mindset more commonly applied to racism. If we believe that only bad people can be racist, then we’re far less likely to explore and own our racism.

But such a binary ignores the complexity of our world. In a racist world, as a White American, I can internalize racist thoughts even as I try to be a good person.

The same is true with gender discrimination, as Maisha Z. Johnson argues thoroughly here. The good/bad binary is a set-up to ensure problematic behaviors go unchecked.

Yes, I was a good kid – a good student, a good employee, and a good athlete. But that all of that goodness didn’t mean I was a good boyfriend. My resume of goodness didn’t negate all of the damage I’ve caused.

It didn’t negate the time I shouted at my girlfriend so loudly during an argument that a neighbor called the cops. It didn’t negate all the times I policed the clothing choices of my partners. And it doesn’t negate that I continue to struggle to find better outlets for my anger than yelling.

And just like I need to face my privilege and racist thoughts, I need to face these behaviors. I need to own that damage, not avoid it.

Understanding the set-up of the good/bad binary has helped me do so.

***

So how did go from that embarrassing mess of a young person to a less messy 44-year-old who spends so many of his waking hours challenging systems of oppression?

The non-memoir answer is intersectional feminism – the framework of all frameworks.

Maybe it was anti-racist work that led me to feminism, but feminism deepened my understanding of these powerful systems that cause so much pain, systems of which I no longer wanted to be part.

And feminism led me closer to my true self and it brought me to that DV organization, which was created by feminism. And while I wish I had learned these insights sooner, I’m forever grateful to feminism.

As an anonymous Everyday Feminism contributor writes:

I am forever thankful to have stumbled upon this brilliant ideology that names my realities and shows me how the culture is to blame, for giving me a framework to understand why what’s happened to me has happened to me, and why the world is so painful to so many.

But don’t get me wrong: I’m not done learning. And this piece is by no means an exhaustive list of the shit – present and past – that I need to own.

And I didn’t write this so I can pat myself on the back.

I wrote this so that more cis men can better understand their toxic behaviors.

And then they can free themselves of them so that they are not messaging apologies twenty years too late.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Jon Greenberg is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is an award-winning public high school teacher in Seattle who has gained broader recognition for standing up for racial dialogue in the classroom — with widespread support from community — while a school district attempted to stifle it. To learn more about Jon Greenberg and the Race Curriculum Controversy, visit his website. You can also follow him on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter @citizenshipsj. Read his articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32