Person doing makeup while looking in the mirror

I want to start this by noting that I am by no means an expert on the study of trauma. I am, however, an expert of my own lived experiences. I am taking this opportunity to shed light on a topic that is rarely highlighted.

I don’t believe there is a “right” or “wrong” answer when it comes to trauma. There are power dynamics that are complex; fitting things neatly into a binary never serves us. This dialogue between trauma and our gender and sexuality is unique for every individual, relationship, and cultural context.

Here’s What We Know

Here’s what we know about trauma: It almost always changes us.

As all of our experiences mold us into who we are, so does trauma. Some people live with the psychological impacts of this trauma through PTSD, for example. Most people deal with their trauma in ways that can’t be categorized. I witness this within my family, as people who emerged from American imperialism and civil war in Vietnam.

Through trauma, our relationship to the world changes.

Much of the trauma that I experienced as a feminine child assigned male at birth led me to build a guardedness and vigilance when it came to my surroundings.

Just as that trauma shaped who I was on a fundamental level, it shaped the parts of me that are relational to my world.

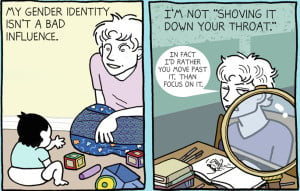

My gender identity and expression is in flux as it relates to my history, my culture, the language I have available to me, and the worlds I live in. But this idea isn’t represented in most understandings of gender that are presented in mass media.

Lady Gaga has made the phrase “born this way” famous; it has led to the idea that all LGBTQIA+ people experience their identities the same, despite the fact that gender and sexuality are two related, but completely different things. Most trans people are represented as being in the “wrong” body, as being born with a discrepancy. This narrative is certainly true for many trans people, but it is not the only narrative. The way it has become the dominant narrative has led to the idea that all people were born into their gender identity.

I am an advocate for people owning their story, but I have questions.

How is one born into an identity that they can’t articulate? How can one be born into an identity without knowing what exactly they’re identifying with?

What I’m getting at is that people like to simplify trans narratives to the point where they feel disingenuous and even dangerous. It reduces us to more tropes that nourish feel-good liberals.

The Problem with Singular Narratives

I surely was not born trans. I was born into a world that punished me for acting the way I acted.

I moved through the labels – straight, then gay, then trans – because I was figuring shit out. It took me almost two decades to begin to understand and resolve my feelings with a world that wanted to attack me constantly.

I wasn’t born with gender dysphoria. But I certainly developed it over the years as I reconciled my body with white-washed, traditional ideas of femininity. And on top of that, I had to cling to what could provide even the smallest amount of safety as a trans girl.

There were a lot of traumas – from sexual violence and from enacting masculinity for years – that took me down to road to trans womanhood. It was not a cut-and-dry process. It was not a M-to-F 60 Minutes special.

Saying that I always knew who I was would be dishonest, but I think sometimes we have to be strategically dishonest to get what we need – just as when trans people have had to prove that they have dysphoria to a cis doctor by spitting out a story of suffering that was delicious and easy to consume.

I think the move to say that our transness comes natural to us, something outside of our control, is strategic for some. The state of trans people’s lives is no joke. We are attacked in health care, education, and the workplace. We are under attack by law enforcement, civilians, politicians, and those who are meant to nurture us.

It’s a wonder how trans people trust anyone.

It’s logical that so many trans people attempt to take our lives. This is especially true for transfeminine people and even more so for Black transfeminine folks.

Jamie Lee Wounded Arrow, 28. Mesha Caldwell, 41. JoJo Striker, 23. Jaquarrius Holland, 18. Tiara Richmond, 24. Chyna Doll Dupree, 31. Ciara McElveen, 26. Alphonza Watson, 38. Chay Reed, 28. Brenda Bostick, 59. Sherrell Faulkner, 46. Kenne McFadden, 27. Kendra Marie Adams, 28. Ava Le’Ray Barrin, 17.

Take a moment to read these names. They were people who had dreams, aspirations, families, loved ones, fears, and hopes. If you search up the cause of death, most of them were murdered by gunshot or stab wounds. The viciousness of trans deaths symbolizes exactly how deliberate and malicious these killings are.

And these are just the reported murders. There are possible unreported deaths due to the body not being identified or the body being reported with the wrong name and gender. I am certain some trans deaths simply go unnoticed.

With the level of danger that many trans people endure every day, coupled with the seductive “American Dream” that so many marginalized groups desire, the “born this way” narrative could be about safety.

The logic goes: If we talk about ourselves in a way that makes us easier to understand – ultimately less human – maybe people will be comfortable enough to give us the dignity we should have had in the first place. If we neatly package ourselves in ways that don’t leave any room for scrutiny, we can be the perfect models of oppressed peoples.

So when people pull out the trauma from the formation of identity that people go through, it’s so that there’s little room for pathology.

Prior to the passing of Obamacare, health care providers could refuse services to trans people because they considered transness a pre-existing condition.

There’s a relationship between trans people and trauma that makes sense – denying it is strategic because trans people are pathologized simply for being trans in the first place.

What We Should Strive For

I wish we lived in a world where all trans people’s narratives held equal weight. But the reality is that some trans narratives are simply more appealing – even among trans people.

There is so much trauma among trans people that ignoring it is not just dangerous, it’s also self-defeating.

Dissociating ourselves from pathology may be strategic in the short-term, but it only reinforces ableism – the idea that only certain bodies are worth respect and dignity. Trans justice should be unconditional, and should be tied with all liberatory movements, including the fight against ableism.

Just as so many trans people live with trauma, many trans people live with mental illness. Trauma and mental illness need to be included in trans narratives. We shouldn’t be striving to be

respectable. We should be striving to be as honestly human as possible. The “crazy” trans person is just as important to me as the cookie-cutter Barbie doll trans person.

Trans people are allowed to be more than just trans.

Trans people are also racialized people who experience trauma from slavery, colonialism, and other forms of state terrorism. Trans people are also low-income people who navigate alternative economies. They’re also parents and artists and athletes and all the things that people don’t imagine trans people doing.

We are not just what people see on TV or magazines.

The reason I’m compelled to argue for our right to claim our traumas is because dissociating our traumas from our identities can be a way to dehumanize us in a world that needs no help doing so.

I learned so much about other people when I gave myself permission to be all versions of myself at all times.

What I hope for, what I’m willing to fight for, is a world that honors all bodies, and all stories. Including those of trans people who are supposedly hard to love because they dare to be human. I love us.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

xoài phạm is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. They are a Vietnamese femme. They are tender and dangerous. They love mangos. They have places to be and people to scare. Read their articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more