Group of people sitting together on the floor

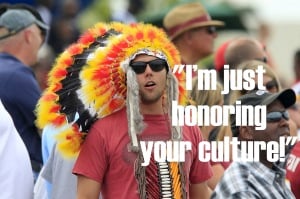

Wouldn’t it be amazing if you could get all the cool stuff that Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) get? Like…

- Richly artistic cultures that have been setting trends in music, dance, art, and fashion for hundreds of years

- Ancient and powerful cultural and spiritual practices passed down through generations

- Seasoned food

Without all the problems like…

- Disproportionate incarceration and extrajudicial murder

- Higher incidence of low self-esteem, depression, and suicide

- Decreased life expectancy

There is a way to get lots of the good stuff and avoid lots (but not all) of the bad stuff!

It’s called being light-skinned or white-passing!

Really though. Don’t get mad, my fellow light-skinned and white-passing BIPOC. I’m not saying that we don’t face many of the same problems as other BIPOC. But it’s ridiculous to deny the fact that our experiences are easier than darker-skinned people’s.

There are too many concrete statistics to the contrary.

To be fair, us light-skinned and white-passing people cannot just snap our fingers and nullify colorism. We cannot return our privilege to the Privilege Store.

But, there are some things we can do to address our privilege, like not automatically assuming that we are entitled to be in all BIPOC spaces all the time.

Are Separate Spaces Based on Race Racist?

Dig, if you will, the picture:

A group of gazelles gathers by the watering hole to strategize about how to avoid being eaten by lions. Also just to kick it and admire each other’s stripes and horns.

A group of lions gathers on the plains to strategize about how to catch and eat gazelles more effectively. Also, just to play a round of golf and talk about wealth management.

Lions find out about gazelles gathering together and get very upset, calling the gazelle’s separatist meeting unfair and reverse speciesist. They demand that lions be able to attend gazelle meetings!

After all, aren’t gazelles allowed to attend lion meetings? It’s just a coincidence that gazelles who attend lion meetings sometimes get mauled and eaten.

You think I’m being funny but I’m not.

See, the way that this society is set up, Black, Indigenous and People of Color — especially those who are Black and Brown with darker skin tones — spend an inordinate amount of time trying to avoid the dangers of racism that are instigated by white people.

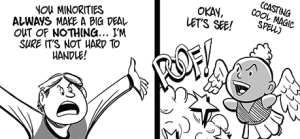

Meanwhile, the reaction of your typical white person to BIPOC expressing the levels of anxiety and terror they must manage while navigating emotionally, economically and physically violent white supremacist spaces is ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Pop Quiz!

In this context ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ means:

- IDGAF

- Hands thrown up incredulously as if to say, “I don’t know understand why you feel that way! I don’t see color!”

- “Why couldn’t Kanye just accept that Taylor was the better artist? What’s the problem?”

- All of the above.

Answer Key

Why, when BIPOC decide to gather for various reasons in the face of a society that systematically seeks to subjugate them, is it such a problem for white people?

Could it be that white people are afraid of what could happen if BIPOC divested from white institutions and ways of being and sought self-determination and independence instead?

BIPOC throughout history have spent much time and energy building our own spaces only to be met with disapproval, petty meddling, violent threats and horrific violence.

In the face of all this, BIPOC have even taken the time to explain to white people and our own people why it is okay and possibly advantageous to have separate spaces.

Yet we still encounter white people who want to know why it’s okay for BIPOC to gather but not okay for white people to form their own separate groups.

Problem is when white people gather separately we end up with groups like the KKK, Stormfront and the Trump White House (please avoid ‘splaining about how the cabinet is not actually completely white).

Bottom line: When life, wellness, and happiness are at stake, Black, Indigenous and People of Color have a right to gather without white people in order to address issues that are important to them.

Or even just to gather socially without the fear or inconvenience of having to worry about whether white people will insult them or act awkward.

Similarly, darker-skinned BIPOC may also desire spaces where they can process and organize around the unique issues they face because of their closer proximities to Black and Indigenous skin tones and facial features and that us lighter-skinned people do not have to worry about.

I’m Stalling

It’s easy to create a funny and provocative headline before you have to actually write it. Then you talk about it with people and realize that everyone has so many feelings. But feelings are okay, even my own, so let’s keep going.

Psst… I’m Not Making This Issue Up

In some areas, separate spaces are simply not possible because of lack of large populations of BIPOC. So this question is a moot point.

However, I have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for the last 11 years, a place considered a mecca for social justice activism and vibrant BIPOC culture. I have been a part of many groups and events organized exclusively for BIPOC.

And every time I have been a part of putting together or attended such a gathering, the issue of whether very light-skinned or white-passing BIPOC should attend has come up.

At the very least, people have expressed annoyance that white-passing people seem to feel entitled to BIPOC spaces and/or get upset if someone questions whether they are BIPOC.

While some might argue that such comments are petty or inconsequential, I think it’s worth taking a pause to consider any issues that darker-skinned BIPOC bring up regarding colorism.

Besides, these tensions make sense since they arise out of the reality that colorism has been present since the first times Black and Indigenous women were raped by white men during colonization and slavery and then gave birth to mixed-race children.

To this day, light-skinned and white-passing BIPOC still receive economic and social advantages over their darker brethren despite all the writing, scholarship and discussion around colorism that is out there.

It must be very frustrating to know that someone of the same race as you can enjoy benefits that you cannot access and to know that they never have to worry about things that you worry about every day simply because of the lightness of their skin and facial features that are considered “finer” — AKA more European.

It might also feel startling to walk into a space that was advertised as BIPOC-only and see blond-haired, blue-eyed people who look whiter than the marshmallows in an Ambrosia salad.

Rather than being defensive or complaining about how we are being excluded from spaces, light-skinned and white-passing people might take a moment to think about what the impact of our presence is in the spaces that we inhabit.

Because let’s face it, us light-skinned and white-passing BIPOC — especially those with white parent/s — still get pretty defensive sometimes when BIPOC vent about the racism or poke fun at the cultural habits of white people.

Other BIPOC don’t really deserve to have to deal with our growing pains of sensitivity, defensiveness, and fragility when they were hoping to be in spaces that are safe from racist or colorist microaggressions.

Appearance Vs. Identification

Because identity is considered deeply personal, we are discouraged from questioning another person’s identity.

Being able to determine whether someone appears to be Black, Indigenous or a Person of Color is complicated and contested, and often depends on many different factors and contexts. For example, some BIPOC may only be seen as such when they are with other BIPOC.

But the examples of former NAACP leader Rachel Dolezal and respected Indigenous Studies scholar Andrea Smith, people who were enriched through claiming BIPOC identities even though they may not have any BIPOC ancestry, have highlighted that there might be a problem with uncritically accepting self-identification.

However, we know that one’s race and skin tone determines material factors such as health, income, and life expectancy, so to pretend that how one is perceived by the world at large has no correlation to how one might choose to identify doesn’t make sense either.

If a person has a BIPOC parent or grandparent and looks white, is treated as a white person, and was raised culturally white for most of their life with little exposure to other BIPOC, where does one draw the line?

Part of the problem may be that in the US we tend to talk as if race, ethnicity, and culture are equivalent, rather than related.

For example, a person can have mostly white European ancestry but due to their family immigrating to a Latin American country, may have been raised Latinx and strongly identify with Latinx culture.

Generally, Latinx people in the US are considered BIPOC. So a person with mostly European ancestry could be BIPOC in this instance and may show up to the next Black and Brown kick back wearing hoop earrings and a huipil blouse.

Does this section make you feel uncomfortable? It makes me feel uncomfortable! Maybe that means we are getting somewhere.

Or maybe it just means that this is a fraught subject. No one wants to go around policing membership into BIPOC-ness when it was white supremacy that created these imaginary categories in the first place.

These Final Thoughts Will Probably Not Feel Very Satisfying But They Are Important

Should you exclude yourself from people of color spaces as a light-skinned or white-passing person?

I can’t answer that for you. There may be no answer.

However, problems arise when us light-skinned and white-passing BIPOC fail to ask ourselves this question or freak out when others ask it.

Next time, before entering a BIPOC space, I would like to encourage light-skinned and white-passing people to read this helpful article by transpinay philosopher b. binaohan and consider the following questions:

Why do I want to be a part of these spaces?

Is it solely to be accepted, to be reassured by other BIPOC that I belong?

Is it to build community with the loved ones and inner circles of people who constitute the spaces in which we might have the most impact in our work to change the world?

Is it to hold space and compassion for the anger and resentment that darker-skinned Black and Indigenous people might have as a result of bearing the brunt of white supremacy’s abuses?

Is it to build solidarity with BIPOC communities so that we can fight injustice together?

Is it to move back by not dominating discussions and not rushing to take on leadership roles that could be filled by darker-skinned people?

Is it to humbly ask what we can contribute to the struggle?

Is to strategize around how we can use our perceived proximity to whiteness in order to destabilize white Supremacy?

***

I think you know where I’m going with all this, right? Humility, compassion, and patience are traits all people to strive toward, but it may just be a prerequisite for those of us with more power seeking connection, support, and solidarity from our communities.

Feeling entitled to space and the emotional labor of reassurance or favorable treatment is what often gives us light-skinned and white-passing BIPOC a bad name.

So keep this in mind — it may just be the reason why your people give you side-eye when you walk into a room.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Nico Dacumos is an Everyday Feminism Reporting Fellow. Nico is a lower-middle class and college-educated child of a Manila-born Ilocano and a Central California Chicana. He currently writes, teaches high school, runs a decolonial food pop-up, builds spiritual community, loves, co-parents, and instigates non-binary transgender faggotry in Oakland, CA.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32