Person in hijab standing in front of building.

When I was in 9th grade, I asked my mother to be homeschooled. It was about five years after 9/11 and I still wasn’t used to people’s stares on the streets.

There was that one time when a man chased my mother down a store aisle, yelling at her to leave the country.

My mother said yes to homeschooling and, during that time, I used to watch Glenn Beck’s show and CNN religiously. I memorized every possible way that one could label someone an Islamic terrorist or a Muslim extremist.

I wrote emails to Glenn Beck’s shows, to Anderson Cooper’s blog posts, and anywhere that had a comment section — I felt that I needed to explain myself and my existence.

The world seemed like a dark place to be a Muslim, so I mostly avoided the public.

I rarely went out shopping with my mother or wanted to be seen outside at all — the world was as big and as hateful as the comment sections of the internet. After countless attempts at changing people’s minds, they remained hateful.

I continued responding to Glenn Beck and many other pundits who spewed how oppressed Muslim women are. But, no matter how much I tried to explain my 9th-grade humanity to the world, I was always reminded that this was not a place for me.

I remember responding to multiple comments at a time, trying to explain to them that I was not oppressed — that I was allowed to go to school and could make choices, even as young as a young teen.

Whether or not I fully comprehended the sweeping generalizations I attempted to convince others with, I was desperate to believe that, somewhere, outside my home, there was a place for me to belong.

Looking back now, I can’t help but feel incredibly sorry for that child who lived as a contradiction every day; to be simultaneously pitied but seen as a threat is not an easy dilemma.

This continued on as I studied more of the Western world’s oppression towards people of color and Muslims throughout my college years. This obvious contradiction was startling for me and one that I could not grasp.

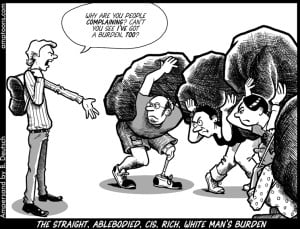

As a Muslim woman, how could I be meek, oppressed, and weak but also the symbol of the largest threat to the Western public?

I was a bundle of both these worlds, but many were unaware of the internal struggle it took to respond to both of these accusations.

Especially the notion that we needed to be saved from the men in our lives — these men, who are also victims of FBI surveillance, imprisonment, and torture — the terrorists who terrorize us and the rest of the world.

A few years back I wrote a poem about the impact of the occupation of Iraq’s impact on Iraqi women, specifically the story of a young Iraqi girl raped by U.S. soldiers, and I ended it with a line that reads:

I wonder if they ever talk about her in their conferences / clanking forks and knives over stories of how to save women from men who are already dead.

The idea of saving Muslim women comes hand in hand with implementing a system of violence against Muslim men.

France’s ban on the headscarf or the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan — following Laura Bush’s call to save the Afghan women — became prime examples of this contradiction, of the world where we are both the threat and the victim.

When I say we are labeled as the largest threat to the Western public, I don’t specifically mean as opposed to Muslim men. I meant that ‘Islamic terrorism’ in general is a threat — men AND women represent that. But men don’t also have to struggle with an oppressed image.

Two weeks into the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan Laura Bush spoke out, stating:

“Civilized people throughout the world are speaking out in horror — not only because our hearts break for the women and children in Afghanistan, but also because in Afghanistan, we see the world the terrorists would like to impose on the rest of us.”

When we are the frontline receivers of the attacks but also of the world’s militant sympathy, it becomes a contradiction. How are we the ones that need saving but are always the ones attacked?

This is a consistent theme that took a long while for me to grasp. My headscarf was a symbol of my oppression and weakness but I also felt unsafe and tense anytime I was around people who firmly believed in my oppression.

If the headscarf is the symbol of the oppression of women who need to be saved, how is it that women with headscarves are rejected from jobs or not allowed to continue their education?

If spaces that are meant to help women progress then why are they the institutions that are, often, at the forefront of denying women their basic human rights?

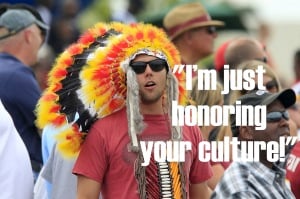

In 2010, in France, a parliamentary report was published that described “the full-body veil as a symbol of the inferiorization of women,” “the first chain link to enslavement,” and concluded that a ban would “liberate women” thus reaffirming “France’s support to persecuted women all over the world.”

This then translated to outright banning said ‘oppressed’ women from accessing employment and education — but aren’t these necessary ways to liberation?

The idea is that the West cannot fathom the idea that covering is a choice and only ever a reality through coercion of a male family member is reflective of the West’s own views on Muslim women: that we ARE weak and that we ARE unable to make our own choices.

This is tied to a Western desire to deny women access to public life — it boils down to an inability to see us as enough or even capable.

It is not out of a desire to liberate as much as it is to use an argument to further exacerbate what has been present in many centuries of racism and xenophobia against people of color in much of the West.

It is easier to get away with using liberal jargon and words like ‘liberate’ and ‘free’ when it only further creates racial and ethnic segregation in communities and societies that are pure ‘Western’ spaces.

This contradiction was seen with Laura Bush, who was the vocal leader in supporting the military invasion of Afghanistan after September 11 by utilizing the plight of Afghan women and their need to be ‘saved’ by the ‘civilized’ world.

The icon of this oppression was seen as the Afghan ‘burqa’ that many women wore.

After the invasion, Laura Bush stated:

Because of our recent military gains in much of Afghanistan, women are no longer imprisoned in their homes, they can listen to music and teach their daughters without fear of punishment.

The ‘liberation of the weak woman’ was a narrative that was pushed throughout the few years of the invasion.

This is what Indian feminist theorist, Gayatri Spivak, stated when she wrote her essay ‘Can the Subaltern speak?’ when she wrote that, “White men are saving brown women from brown men.”

Now that women do not have to wear burqa in Afghanistan — even though there was not a drastic decrease 16 years after the invasion — are Afghan women less oppressed?

What is liberation if, 16 years later, thousands of Afghan women have lost their lives to this war and are living in incredibly dangerous realities due to the constant violence and cycle of threats they endure?

Growing up, I did not know what to make of these contradictions. For a long time, I attempted to prove that I was capable of juggling both identities: the strong girl who was not weak but also the soft one who was not a threat.

After 9th grade, I decided to end my homeschooling experience. During the one year I spent at home, I experienced an isolation that forced me to delve deeper into asking questions and reading as many books as I could.

During this year, I was introduced to books that have shaped the person I am today, books that I still keep close and revisit often.

Although I grew that year, and credit my parents instilling in me the values of pride and courage, this decision is not one that I would hope my children would take.

Being a post-9/11 Muslim, Brown American girl is unique in that this paradigm was unique to the time we were living, something my parents or anyone else could help me understand.

Having experienced the crisis of representing multiple contradictions or identities, I hope to equip my children with necessary conversations to be able to be comfortable in their skin and more aware of the rhetoric around them without being consumed by it.

The complexities of these conversations and my journey reaffirm that I want my children to experience the world as it is, fully aware of it, and understanding their place in it. But also celebrating that space and making sure that they are aware of the power they hold.

After years of questions, insecurities, and an inability to fully grasp my circumstances, it dawned on me that no matter how much I tried to be either/or I was never enough.

If it was not my headscarf, it was my name; if it was not my name, it was my faith or my ethnicity. There will always be a need to save me from something that, in turn, will oppress me again.

I want to end this with a great quote from an amazing essay by Lila Abu-Lughod titled, ‘Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?’ where she speaks about the war on terror in relation to saving Muslim women.

This essay was incredible in tying together the vilification of Muslim women and the relation to U.S. foreign imperialism.

It was crucial at a time when U.S. violence in the Muslim world could be linked to ‘saving’ the Muslim women and remains crucial for anyone interested in Western feminism and its link to Western imperialism.

Abu-Lughod states:

We do not stand outside the world, looking out over this sea of poor benighted people, living under the shadow—or veil—of oppressive cultures; we are part of that world, Islamic movements themselves have arisen in a world shaped by the intense engagements of Western powers in Middle Eastern lives.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Hadiya Abdelrahman is an Everyday Feminism Reporting Fellow. Hadiya graduated from Rutgers University with a double major in Women and Gender studies and Middle Eastern Studies. Hadiya currently works with refugees and asylees in NYC. When she’s not at work, Hadiya writes angry rants and poetry. She enjoys writing about topics that focus on refugees, intersectional feminism, and state violence against people of color.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more