Two young people looking at a smartphone.

My parents are first-generation immigrants from South Asia who came to the United States in the 1970s. Whenever I ask them if they’ve experienced discrimination in this country, they respond with some iteration of “no, not really” every time.

Now, my parents are brown — they are. So some of you might be surprised that they would respond in this way. Brown and South Asian in America? Like, damn! But Apu from the Simpsons, though! But anyone who’s not white, though! And they’re immigrants?

Okay, my parents are South Asian immigrants, but they’re also fairly light-skinned, Hindu, upper-caste, and Indian. And this is pretty crucial to why they respond in the way they do.

It actually also has a lot to do with United States immigration laws.

In a newer wave of U.S. immigration policy, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. The act based its guidelines for entry on “professional status and family reunification.”

This policy, along with socio-economic divides exaggerated by the caste system, and the expanded education system in India, allowed for the entry of “skilled” Indians to immigrate to the United States in large numbers. In the book Bengali Harlem, Vivek Bald remarks that “while it seemingly put an end to the exclusion era, the 1965 act essentially maintained the exclusion of working-class immigrants.”

As a result, Indian Americans are now three times more educated than the US population and have a higher annual median income than other Asian Americans, as well as the general US population.

Indian Americans also have higher annual median incomes than other South Asian groups in the United States, including Sri Lankans, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis.

What’s my point? Well, that many Indian Americans have a good deal of comparative class privilege.

Why am I making this point? Not because I think that Indian Americans don’t also experience oppression, or that I want to undermine our experiences.

But because putting us all under the label ‘South Asian’ can invisibilize some folks in our communities and prevent us from understanding the significance of the diversity that exists amongst us.

So, what are some of the factors that make us diverse, and complicate the question of the extent to which South Asian Americans are ‘oppressed’?

1. Our family’s socioeconomic status pre- and post- immigration

As I’ve said, socioeconomic status is pretty varied in the South Asian American community.

Of course, socioeconomic status, or class, is a huge determinant of privilege in the United States. And in our countries of origin, systems of social stratification exist too.

The caste system that was prominent in India has played a large role in South Asian social stratification.

And though it’s easier for a lot of people to deny it than to confront the inequalities that it’s created, it has left a scar not only on Hindus in India but on many other South Asian groups as well, with multiple religions and countries of origin.

Upper-caste South Asians have structural advantages that stick with us for generations — when we’re living in South Asia but even when we’re abroad.

Even though I was born in the States, I still grew up with class privilege due to my parents’ upward mobility. And how did they gain that upward mobility?

Partially through the class status that caste afforded them in India, which helped them to become “professional” workers that were appealing to the United States’ immigration policies!

2. Our different immigration processes, and statuses

In Bengali Harlem, Bald claims that the stories of early working-class South Asian migrants have been lost “to history in large part because popular understandings, expectations, and myths about immigration to the United States render them invisible or illegible.”

And, this is highly relevant to the present too, being that our discourse on South Asian experience does not adequately represent stories of people who aren’t perfect model minorities.

Did you know that one out of every seven Asian immigrants to the United States is undocumented?

Most undocumented South Asians come from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka; and many of them are DACA recipients.

So, while many South Asian Americans struggle with the immigration process during and after arriving in the United States, there are also South Asians who are confronting the possibility of deportation with Trump’s plan to end DACA.

Additionally, according to South Asian Americans Leading Together, the South Asian American community also includes “dependents, and temporary workers on various visas, refugees and asylum-seekers, lawful permanent residents, and United States citizens.”

3. Our religion

South Asian Americans aren’t only Hindu — they also practice Islam, Sikhism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity.

Our religions often receive different attitudes by the U.S. public, too. People have both mocked and fetishizingly revered me (all white girls) when I reveal that I was raised Hindu. They sometimes end up going to India to find themselves because they find Hinduism so “life-giving.”

I have also had Sikh friends, though, whose family members have been tormented for wearing a turban, and Muslim friends and partners who face the uncertainty of violence towards themselves and their family members every day.

Plenty of non-Muslim South Asians fear discrimination if they’re ‘perceived to be Muslim.’ And this fear is not unwarranted.

Non-Muslim South Asians, especially Sikhs, have experienced violence and discrimination because of their perceived proximity to Islam.

But, as opposed to (upper-caste, Indian) Hindus, Muslim South Asians experience not only erasure in conversations about South Asian identity, but also the direct violence of antagonistic rhetoric and political surveillance towards them both inside and outside of the United States.

My Hindu grandfather fled from Pakistan during the Partition, and he still holds a lot of internalized Islamophobia to this day.

That’s to say that it’s all of our responsibilities especially as non-Muslim South Asians to commit ourselves to combating Islamophobia in and outside of our families, through donations, personal interventions to derogatory or ignorant speech, or public protest.

4. Our gender

When speaking about both gender and sexuality in South Asian diasporic cultures, it’s impossible to not talk about colonialism.

Prior to colonization, it’s proven through art and history that South Asians demonstrated fluidities in gender and sexuality. Colonialism deeply influenced the ways that South Asians practiced gender and sexuality, with altered ideals for behavior and desirability.

So, when we talk about South Asian femmes in the mainstream, we usually mean cisgender, heterosexual, light-skinned, and submissive women who fulfill fetishized ideals of South Asian feminine beauty.

But lots of South Asian American femmes actually live in resistance to these ideals and there are many South Asian Americans who resist their (gender) stereotypes.

There are also those of us who resist the cultural labels assigned to us all together —South Asians who are are trans, non-binary, and genderqueer.

I am non-binary and gender-expansive. Embracing this identity has been a place for spiritual and emotional growth for me but, for my South Asian family and community members, it’s something worthy of shame and embarrassment.

5. Our skin color

Colorism runs deep in South Asian communities — in South Asia, and in the diaspora. Embedded in the ideal for light skin are also notions of purity, socioeconomic status, and desirability.

And, often, to be desired is also to be loved, valued, and respected.

The South Asian American community is comprised of a range of skin colors and facial features, from the descendants of working-class South Asian men who formed families with Black and Latinx women, to people like me — fairly light skinned Indians with features that fit a number of Eurocentric ideals.

It’s important to recognize that hierarchies based in colorism do exist amongst us, and make for really different life experiences.

***

This diversity amongst South Asian Americans is important to consider for us to be able to interrogate the ways that we are situated within our communities.

We should absolutely share our stories, and advocate for ourselves, but we also can’t pretend that we all share the same experiences, or that we can always center ourselves in conversations about violence against Brown people.

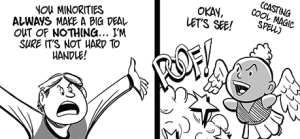

For the more structurally privileged amongst us especially, we really need to stop using our Brownness as a shield to deflect from recognizing our privileges.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Ayesha Sharma is a non-binary South Asian scholar and artist continually negotiating a relationship with themselves and their communities through practices of decolonization. They are most interested in literal and symbolic reclamation as an art practice and investing themselves in community care. Ayesha has written for the Urban Democracy Lab and is published in ANTYAJAA: Indian Journal of Women and Social Change.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more