Person looking off into the distance with their face resting in their hand.

In my lifetime, I’ve constantly been asked probably hundreds of dehumanizing and frustrating questions that have left me exhausted.

Here are just a few:

“I take pictures of cute Asian girls for my website. Can I take your picture?”

“What are you? Indonesian? Japanese? Korean? You can tell me what you are, right?”

“I’ve always wanted to have sex with an Asian girl. Good thing I found you.”

“Do Asian girls really have sideways pussies? Can I see?”

“You think you’re better than me, don’t you? All of you Asian bitches are the same.”

“I am so excited for you to have Asian babies with my son!”

When I talk about my experiences with white friends, they express disgust and shock as I tell my story or stories. They are sympathetic and listen intently to what I have to say.

They are appalled and dismayed by how I have to play into the stereotype of the polite, domestic, hospitable Asian woman so that my harassers will leave me alone so that I can escape.

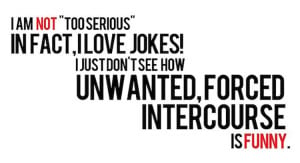

Then, they say: “How could they do this to you? How could they say this to you?” and these are questions that have complicated answers. The relationship of Asian fetishization to white supremacy is rarely explored or explained but is present in every corner of the space it creates.

It is a relationship built on a foundation of war, colonization, dominance and control. It is systematically abusive, it is a force of erasure, and it is a way of maintaining an unequal balance that benefits only the oppressor.

The confusion of my white friends shows me just how much white supremacy, and whiteness in general, blinds white people to oppressive experiences and their consequences.

I am a Japanese Greek American, and I cannot speak for everyone, their experience, or how their experience is influenced by their identity. But I can share several defining characteristics and histories that speak to a larger, collective truth of our experiences and identities.

Here are some of the ways that white supremacy manifests in Asian fetishization:

1. Asian fetishization erases oppression of non-East Asians.

Non-East Asians should absolutely not be fetishized. They are subjected to this as well, but the conversation around their experiences is not given nearly the same amount of representation or attention.

Asian fetishization is a phenomenon that fixates itself on a false image of East Asians, who are stereotyped as skinny, fair-skinned, able-bodied and submissive. It ignores the suffering of Filipino sex trafficking victims (also, Filipino people are often excluded from representation and discourse around Asians, in general).

It ignores the suffering of South Asian women who are subjected to labour trafficking, exploitation, and abuse.The entitlement of these workers to the bodies of their victims is largely informed by Western imperialism, and its manifestations feed directly into white supremacy.

In short, endless histories, issues and dialogues are ignored by those who fetishize a small fraction of Asian identities. “All Asians are the same.” We are not.

The history of colonization between Korea and Japan, and the abuse of Korean and Chinese “comfort women” by Japanese soldiers during WWII is an example of this.

“All Asians are the same” ignores the Uighurs, who are both Central Asians and Turkic. Their current living conditions— if they can even be called that—in China are abhorrent, and I have never heard my friends talk about it.

The visibility of these issues is lacking because of the absence of representation of non-East Asian histories, countries, and dialogues.

Countries such as the Philippines, Nepal, India and Thailand have been systematically destabilized by colonial forces, and become feeding grounds for Western aid workers who target children and women for low-consequence rape, sexual assault, and cheap sex work. Asian fetishization acts as a blinder to the oppression of those who do not fit its limited gaze.

2. Asian fetishization doesn’t make Asian people more white.

There are many white supremacists who include Asian people in their rhetoric and ideology as “secondary whites.” Japanese settlers in the Pacific Northwest were regarded as outstanding members of their communities—”proof” that assimilation worked.

However, when WWII came, their census information was used against them to send them to internment camps.

As much as they were led to believe that they were “real” Americans, wartime revealed the truth: Asians are not, and will never be, white.

The model minority model, as applied to East Asians, emboldens white supremacists. Asians are often seen as a testament to the success of assimilation into the American way of life.

By giving a false sense of inclusion, white supremacists give false power to the Asians they win over, and dispose of them when they are no longer useful. However, every time these white supremacists proceed to define whiteness, Asians are explicitly excluded.

3. There is a history behind “Asian girls love white boys”—it is not one of love.

White men often talk about how Asian women “love” them on dating apps, or how Asian women have a preference for white men. This is an assumption based on entitlement and a story of domination and control.

To begin with World War II, culture-shocked Japanese war brides who married American GIs were often subjected to abuse upon arriving in their new homes. Their identities were still vilified as threats by their in-laws, and even by their supposedly loving husbands.

Many of them were despised both by their families back in Japan, and by the communities they were now unwanted members of.

They were forced to change their names to generic American ones, and transform their identities so as to not pose a threat to American ideals. They were belittled into domesticity. They were trapped in a new, painful life that they barely knew, with no presentable way out.

The entitlement and abuse of their husbands was an ugly truth behind the controversial new face of mixed-race “love.” However, this trope has been so reinforced that dating and marrying white men is projected onto the Asian woman’s experience, and how our experiences are seen in movies, books, art, and other forms of media.

These stories often feature the Hollywood version of the colonization and military presence in Japan and other Asian countries after World War II. A recent example of this can be found in Netflix’s “The Outsider.”

As frustrating as this stereotype is, a lot of humor can come out of it, too. Comedienne Ali Wong explained in her Netflix special that “You feel very picturesque when you’re with a white dude, you know. You feel like you’re in a Wes Anderson movie or something.”

Wong draws on more whimsical notions of whiteness to simultaneously push back, and make us laugh as she does it. Additionally, Kristina Wong hilariously explores Asian fetishization and its implications in her essay “I Give Up On Trying To Explain Why The Fetishization Of Asian Women is Bad.”

Women being transported to meet Western desires is not new. Mail order bride services offer clients the opportunity to specifically select women based on body type, ethnicity, personality and appearance (warning, this link is vomit-inducing).

These sites also include tips on how to connect with your new Asian wife, including a guide to her cultural attitudes, how her behavior is influenced by them, and how you can use them to make sure she will be a “good wife.”

The history of interracial relationships between Asian women and Western men is tainted by domination, war, and surrender. This not a story of love, it is one of power and control.

That is the legacy of “Asian girls love white boys.”

4. “Empowered” Asian women in Western media are still dominated and controlled by whiteness.

The limited pool of Asian actresses in Western media limits the power and agency of the characters they depict, and how they are represented. In short, it sucks. One of the biggest stereotypes of Asian women in Western media is the dragon lady. Characters such as Kill Bill’s O-ren Ishii (Lucy Liu), Dr. Cristina Yang (Sandra Oh) of Grey’s Anatomy, Alex Munday (Lucy Liu) from the Charlie’s Angels series, and Knives Chau of Scott Pilgrim Versus the World are all examples of this archetype.

However, the strength of the stoic, ruthless Asian woman is prone to being controlled or extinguished at any moment by a Western character. That is not power.

For dimensional female characters of balanced humanity, begin with Japanese folklore. The stories of our hannya and yūrei are equally frightening, empowering, and sobering.

5. Asian stereotypes are largely informed by American propaganda.

The “Yellow Peril” narrative defined Asian people as threats and the consequences of that bigotry still affects Asians today.

America has a long-standing history of creating propaganda to define an enemy. Cartoons, comic strips, posters, and movies were included in campaigns against the Japanese during WWII.

Because of all this, it is no surprise that similar sentiments are still echoed by top-ranking government officials and in American popular culture. These ideas are still being created today, and they still hold power in how Asian people are seen and treated.

The damage is constantly thrown back at us. The formation of stereotypes, expectations, and entitlement are deeply entrenched in white supremacy, and so are their consequences.

The work of enforcing self-love while reconciling with oppression is hard, but it is being done. It is being built by hand, from the ground up, with intention, heart, and purpose.

Collectives such as Sad Asian Girls (which disbanded in 2017, but the expanse of their body of work cannot be ignored), the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective and Angry Asian Girls mark the power and presence of Asian women today.

To the unwelcome white boys and men: Just leave us alone.

To everyone else: see us for who we are. You do not know us. Do not assign stereotypes and lies to our humanity. Listen to us. Learn. Do not demand our time and labor to explain our experiences, only to dismiss and belittle our pain.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Sophia Stephens is a Contributing Reporter at Everyday Feminism, an Editorial Intern at The Stranger, contributing writer at Youth Radio, and blogger with Kids & Race. Sophia’s primary focus includes social justice, politics, and popular culture. She also speaks at events for organizations such as The Seattle Erotic Arts Festival, the University of Washington’s Viva la Joteria conference, and more. Her/their work has also appeared in The Huffington Post, Rookie Magazine, and The Washington Post.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more