Top view close up of hands touching computer keyboard

As feminists, we know that words have power. So many of the microaggressions we deal with relate to how words are used towards us and to describe us. Intersectional feminism requires that we pay close attention to our words and how they may reinforce racism, sexism, and other oppressions.

How we talk about people, things, and ideas has a huge material impact. Subtle choices between phrases can reinforce certain world views and messaging is crucial to the advancement of political movements.

For example, if someone is writing a seemingly “objective” article about abortion, whether they call people who think abortion should be illegal “pro-life” or “anti-choice” (or pro-abortion, anti-abortion, etc.) frames the debate.

Most articles that you read on the internet pass through an editor, who generally use style guides to help guide their decision making. Before I became a writer, I thought style guides were about fashion, so don’t feel bad if this is an unfamiliar concept to you.

If you went to college, you may have familiar with style guides from the American Psychological Association (APA) or the Modern Language Association (MLA). Style guides lay out what a particular outlet prefers and allows when it comes to language, usage and grammar.

For example, whether or not an outlet allows the use of the singular “they” is a style guide issue, but also relates to a broader political movement for rights and recognition for trans and non-binary people.

As of April 2017 even mainstream sources like the Washington Post, the AP, and The New York Times allow a singular “they” if that is how a subject identifies. If you are still opposed to this change, you are on the wrong side of history.

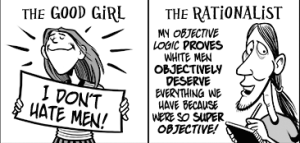

These seemingly small choices have a much broader reverberation throughout the culture and can help to subtly reinforce cultural norms, for good and for bad. Word choice helps prove that objectivity is a myth, as decisions must be made.

A news source that calls Brown people terrorists, but white people “disturbed individuals” is making a choice to frame the world in a certain way. Certain principals unite the style choices that feminist editors make.

I asked editors at three different online feminist publications about their style guides and how they make decisions around language and identity. Here are some of the concepts that came up the most:

1. Make the right distinctions around identity

One outlet that I contribute to, The Body is Not An Apology, capitalizes the “B” in “Black” when referring to identity. I asked mai’a medicine , an editor there, about this policy, as it seems to be rather unique.

This is likely because both the founder of the site—Sonya Renee Taylor—and mai’a are both Black women. They have the expertise that can only come from lived experience. She explained that “in standard written English (we) capitalize all ethnicities, (such as) Indian-American, Asian-American, Latinx, etc, except for ‘Black’. even though ‘Black’ is an ethnic identity clearly.”

Mai’a also noted that “we capitalize African-American, but not Black American even though the two words are describing the same people.” She also argued that “keeping Black lowercase is stating that to identify as Black, is not on par with other folks ethnic and cultural identities. That it is lesser somehow. That it is less important.”

2. Make sure to include context

Like other editorial decisions, mai’a explained that there is a historical element to this discussion.

“There has been a fight to capitalize our people’s name,” mai’a said. “For instance, W.E.B. Du Bois was arguing that we should capitalize the word ‘Negro’ and the New York Times finally did so in the 1940s…as a way to honor the culturally significant contributions of ‘Negros’.”

Historical context is also relevant to understanding how and when to make a change. Erika Smith, an editor at BUST, wrote that she made changes when she came into her role at BUST two and a half years ago.

In the past sex workers were referred to by more derogatory terms (not specifically by BUST, but generally). After she started, Smith added an entry about how “writers should use ‘sex worker’ instead of other terms,” but clarified that if she “was editing a piece by a sex worker who preferred another term, I’d most likely defer to their preference.”

3. Consider Standard Style Guides a Starting Point

In particular, many feminist editors often look outside typical style guides to help ensure their site or publication uses respectful language.

Amanda Chan, the managing editor at Bustle, explains that their style guide is “based on the AP also consulting simultaneously with different groups and stakeholders to make sure our guidelines are as up to date and inclusive as possible—even if that means breaking with AP style.”

Like many other feminist-leaning publications, many of Bustle’s writers are from marginalized groups. For this reason, Chan believes that editors should create space for writers’ lived experiences and identities when deciding whether or not to break with AP style.

After all, AP and other traditional style guides might work for some publications, but feminist editors often face unique challenges that AP may not have contemplated when creating its guidelines.

Such is the case at BUST magazine. Smith explains that the publication is “based on AP style with a few tweaks. Some of those (tweaks) come down to the subjects we cover—we have an entry that says riot grrrl should always be spelled with three Rs—and some of that is just what our editorial team prefers.”

4. Listen to Readers and Writers

Chan sees developing a style guide as a “constant and collaborative process,” and says they often look to writers who have lived experience as arbiters of what language is and is not appropriate. Having writers with diverse identities is crucial if editors want to stay ahead of language as it evolves.

The prioritization of respectful language over strict adherence to a style is typical of the feminist editors I spoke with.

“A lot of (making changes to the style guide) is (about) listening to writers, listening to reader responses, and listening to larger conversations about language and inclusivity,” Smith says. “I defer to writers’ preferences whenever possible, particularly when someone is writing about their own identity or a group they’re a part of.”

5. Seek out Identity-Based Style Guides

Some advocacy groups put out their own style guides in an attempt to help editors and writers respectfully represent and report on specific identity groups.

Such style guides include GLAAD’s media guidelines, the Radical Copyeditor, National Center on Disability and Journalism, a Conscious Style Guide, a Progressive Style Guide, and a Race Reporting Guide from Race Forward.

***

How we talk and write about people is crucial when it comes to respecting identities and furthering social justice as a whole. We need to be thoughtful and critical about the decisions that are made and demand that writers, editors and publications use language in a way that is responsible and non-oppressive.

As readers and feminists, it is up to us to hold media accountable, but first, we need to understand the significance of seemingly small and unrelated rules like what identities are capitalized and how those guidelines work to further white supremacy, misogyny, and other oppressions.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Katie Tastrom is an activist, writer, and lawyer. She writes about living with chronic illnesses, disability justice, fatness, parenting, queerness, bodies, and other stuff. She lives in Syracuse, NY with her four kids and amazing partner. She also watches a lot of TV. You can find more at katietastrom.com or follow her on Twitter at @katietastrom.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more