Young person, enjoying a cup of coffee at the cafe.

The biggest challenge for me in finding social justice and feminism was how inaccessible a lot of the work was. At the time, I was an undergrad in college and my early introductions were through Women and Gender Studies and LGBTQ Studies courses.

I absolutely loved those classes. During classroom discussions and while my professors were talking, I was totally immersed and engaged but I was lost during the assigned readings.

Back in my dorm room, I was Googling things like, “the difference between charity and social justice” to try and understand what I’d read in books like “Power, Resistance and Science: A Call for a Revitalized Feminist Psychology” by Naomi Weisstein.

I’ve always struggled with highly dense, academic texts. I’m autistic, and I process information and communicate differently. It helps a lot if I can talk out a concept with another person who understands it better, or if I can have it explained to me in the context of a real-life example.

While I’m not the first in my family to go to a four-year college, I was raised in a low-income neighborhood and my parents weren’t scholars or academics. They were a cab driver and a medical technician.

The moment it all changed for me was when I read an essay that talked about community change. It was written in the way the author would speak to a friend.

It helped me understand the importance of including community members in community activism work. Before that moment, I didn’t know that it was possible to advocate for justice through writing with a non-academic approach.

As a writer and activist, I’m always asking how I can make sure my work is accessible to as many people as possible, because I don’t want burgeoning feminists to face the same challenges I did.

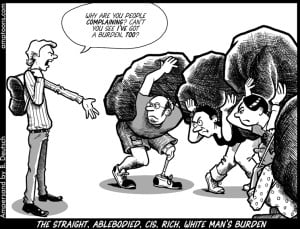

If we’re not doing this work for everyone — for people who are poor and low-income, who are housing insecure and homeless, who don’t have access to higher education, who have cognitive and learning disabilities, whose first language is not English, who need audio transcripts or image descriptions — then why are we doing it in the first place?

I researched best practices from the National Center on Disability and Journalism, and I spoke to accessibility experts and people who need different forms of accessibility to understand: What makes content accessible, and how can we put those efforts into our own practices?

1. Write in plain language.

If you want your work to be accessible, it should be written and presented in plain language. It’s a good idea to use short sections and short sentences, and omit excessive or complicated words. Follow general guidelines and best practices, including this list that’s specific to online content.

If you’re using potentially unfamiliar concepts, define and explain those concepts. It’s helpful if you can offer examples that help illustrate them in multiple different ways.

When I’m reading, I always like a real-life example. It could be from the person’s life, a hypothetical situation, or a news story that’s easy to follow.

Don’t make assumptions that your audience knows words or the details of something that happened, if it was commonly covered by the media at the time. You can’t always explain everything in your own work, but you can link to resources that give readers more information about facts, statistics, and news or current events.

2. Offer multiple ways for people to interact with and learn from your content.

Most of us have a primary mode we prefer to work in, whether that’s written content, audio, workshops and trainings, in-person meetings, video, or another format. It’s worth exploring how you can make your work accessible to people who aren’t comfortable with that method, particularly if you’re part of a larger organization or publisher.

If you’re educating about how people can take anti-racist actions in their communities, for example, and the primary method you’ve been using is a video content series, you might want to consider also writing (or sharing links to) articles and longer works on the topic.

You could have a workshop, online or in-person, for people to attend where they can get deeper into the subject with an educator.

People work and learn differently, so it’s important to have as many options as you can if you’re looking to educate an entire group or community, or offer widespread (local, national, or global) education on a subject.

3. Offer your content for free or with low-cost options.

Cost is everything for many people. I grew up with free learning. Because I was low-income, my parents could rarely afford classes, tutors, or extracurriculars that had an ongoing cost attached.

Paywalls are common with online content, especially since your media site may rely on memberships, subscriptions, or other pay-per-view models to survive financially.

But it’s important to look for ways that your content can be free or low-cost. By putting a price tag on it, you’re already excluding some of the people who need activism and justice work the most.

If you’re not a nonprofit and you don’t already have a budget for free or low-cost offerings, is it possible for you to partner with a nonprofit or social justice organization? Could you partner with groups in the community that might help you, for example, host a space for an educational workshop for free?

When I organized a panel on how to build a career in publishing aimed at Greater Boston area teens, I worked with the Boston Public Library and the Children’s Book Council to find a free space for the event. We were able to offer it at no cost, because everyone who was part of the workshop was a volunteer and we didn’t need to pay for event costs.

If you absolutely can’t offer your content for free or at low-cost to anyone, you could consider offering scholarships, for which community members would apply. It would cover the cost to subscribe to your activism magazine, join in on your online or in-person workshops, take one of your classes, or be a member of your online discussion forum.

4. Make your content accessible to people who are visually, sensory, or hearing impaired.

Anything that’s online needs to be fully accessible.

Make sure you’re captioning and transcribing audio/video content, offering image descriptions, using descriptive link text (“find out more about how to decolonize your nonprofit here,” instead of simply “here”), and avoiding flashing animations among other accessibility practices.

Even outside of your main website, you need to think about accessibility. I’ve been asked a few times in the last couple of months why I offer image descriptions for every link I share on Facebook, as well as for personal photos.

I’m doing it because I know I absolutely have blind, visually impaired, and sensory impaired friends on Facebook who have asked me to provide image captions so they can participate in social media fully.

But it’s something everyone should do—especially writers, activists, educators, organizations, and public figures—because that’s how we make accessibility mainstream.

5. Make your content easy to find and navigate for a wide range of people.

We don’t have a ton of control over Google or social media algorithms, but you can do your best to make your content as easy to find and navigate as possible. If it’s a print magazine, where are you distributing it?

If someone wants a copy, how easy was it for them to order it? What methods of payment do you accept, if there’s a cost? If you’re hosting a workshop, how and where are you advertising it? Are you putting up flyers and doing community marketing in addition to online marketing? How are you going to reach the people who need access to your content?

It’s important to remember here that while technology has made many things much more accessible (e-books are fantastic for many people with visual impairments, for example), it’s not always the case.

Technology is still cost-prohibitive, and you can’t assume everyone in your intended audience has a smartphone, a laptop, or access to WiFi. Tech can also be hard to use, particularly if you’re older, if you have a disability, or if the technology was created in a language that isn’t your native one.

I was recently at the mall and noticed they replaced all their old maps with newer, touch screen maps that will help you plan your walking route to the store you’re looking for. Sounds useful, right?

All I could think about when I saw it was how much it would frustrate my dad and complicate his day, because he really struggles to use touch-screen tech and it almost always gives him trouble. If you’re offering a tech component of your content, like an app, make sure that it’s supplementary to other ways people can access the information.

***

When it comes to activism and social justice work, it’s so important that the content we’re creating is accessible to everyone. If it’s unaffordable, people can’t meaningfully access and engage with it, or people are regularly getting frustrated and giving up on learning or participating, then we’re not reaching everyone we need to reach.

All too often, accessibility is an afterthought. It’s what comes up after a class has already been planned (and costs $599 per month or has a long flight of stairs to get into it), or a book has already been published. It needs to become one of our first thoughts, as central to our thinking and planning process as the content, education, and activism itself.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Alaina Leary is an editor, book publicist, and activist from Boston, Massachusetts. She’s a social media editor for the nonprofit We Need Diverse Books, and has an MA in publishing from Emerson College. Her work has been published in The New York Times, The Boston Globe Magazine, Teen Vogue, The Washington Post, Vice, Cosmopolitan, The Rumpus, and more. Twitter/Instagram: @alainaskeys.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more