Source: Rec Min

In 2005, after decades of identifying as a lesbian feminist, I came out as transgender and transitioned to male. I am much happier as a man, but I have also come to realize what I’ve lost now that I’m no longer one of the sisterhood.

One of the saddest things about becoming a man was moving from a class of people most likely to be victimized to a class of individuals more likely to victimize someone else.

I am now less likely to be raped or beaten or killed. Of course no one would bemoan the loss of being victimized or of being seen as potential prey for the predators among us.

But there is something very sad about becoming statistically more likely to become such a predator yourself.

I first became aware of the magnitude of that shift when I was standing in line at a grocery store. The woman in front of me had an adorable toddler who was staring at me. She was holding onto her mom’s leg with her back to her mom while her mom was unloading their cart.

I have been the object of children’s stares for much of my life.

Kids have no filters and zero embarrassment, so for years they would ask me “Are you a boy or a girl?” and their mothers would blush and admonish their child for asking such rude questions.

But their naive questions were totally valid. The truth was, for a very long time, I wasn’t exactly sure how to answer that question, even to myself.

Around the time I finally decided I was really a boy, I was involved in a work accident that has left me using a cane whenever I have to stand in a line. Now kids no longer question my gender presentation, but they are fascinated by my cane and want to know what’s wrong with me.

So this little girl staring at me was nothing new. What happened afterward was.

I smiled at the little girl in front of me in line. She just stared back. I waved at her. She stared at me. I made a funny face. Her eyes lit up. She mimicked my face.

Almost any woman in this situation would have been greeted with a smile from the child’s guardian for interacting with the child. That had always been the case for me before that day.

But that’s not what happened this time.

When her mother realized her daughter had let go of her, she looked down. At first she saw her daughter smile, and the corner of her own lips automatically curled upward. But once she followed her daughter’s gaze and looked at me, the smile on her face vanished. She pulled her daughter to her and glared at me.

When the little girl looked at me again, I avoided her eyes. But that wasn’t enough. Instead, the mom pushed her daughter in front of her, literally putting her own body between me and her little girl.

That was like a dagger to my heart. And it wasn’t an isolated situation. It quickly became apparent that I had become stranger danger.

Now that I’m seen as a man, women will cross the street to avoid me, especially at night. Women will nervously look over their shoulders at me; if they think I’m following them, they start walking faster. Women will hesitate a moment before stepping into an elevator where I’m the only passenger.

And nurses will ask my wife if I’m abusing her at home. Not long after I began transitioning, Diane cut herself when a glass broke. I drove her to the hospital. Once there, she was separated from me and nurses asked her a series of questions, “Did your husband do this? Do you feel safe? Is there anyone hurting you at home? Did you hurt yourself to escape a bad situation at home?”

By changing my name and taking testosterone, I had become more likely to abuse children and threaten my wife. I had become the enemy.

An invisible wall has sprung up between myself and women I haven’t met, and I’m not to cross it. It makes me profoundly sad that I’ve lost the opportunity to connect with women and children the way I used to.

I wonder what it does to one’s psyche to be responded to this way. What does being cut off from half of humanity do? What is the impact of growing up being feared by the very people you supposedly want to spend your adult life with? Can being viewed as a predator turn you into one?

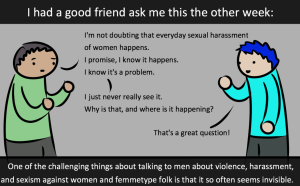

And I wonder why cisgender men aren’t more upset by this. Could it be that they don’t realize that women are guarded around them or even afraid of them? Do they just not know that women fear going out alone at night and that they teach their children to avoid unfamiliar men?

Surely they know that women are raped and beaten by men every day, right? that 1 in 5 American women will survive sexual assault in their lifetime?

Do I only know these things because I used to be a lesbian feminist, because I took Women’s Studies courses, because I was viewed as female for three decades, because I am also a survivor?

One of the things I do know is that, statistically, women and children are more likely to be abused and killed by the men closest to them (family, friends, and neighbors) rather than strangers.

But we — women and men alike — don’t like to talk about that. We’d rather think that such violence only erupts from strangers, especially strangers who are different from us in significant ways.

It’s not surprising that men wouldn’t want to talk about this. Who wants to acknowledge that they are the biggest threat to those they love?

It’s not strange men. It’s you; it’s me. We are the most likely perpetrator of violence against the women and children in our own homes.

I don’t know why violence against women doesn’t make men angrier. Why it doesn’t spur men to action? Why we don’t revolt, why we don’t demand that changes are made so that our wives and daughters are never victimized again? Why don’t more men try to change a culture that often seems to accept or even condone violence against women?

Why don’t more men see rape as their issue? Who do we think are raping those women?

How can we look ourselves in collective mirrors and acknowledge that rapists look far more like our own reflection than we might want?

Although female perpetrators certainly exist, men are still far more likely to be the perpetrators. If 1 in 5 American women will be sexually assaulted in their lifetime, it means someone you know, one of your friends or family members or coworkers (or even yourself) will sexually assault a woman in your lifetime.

Doesn’t that bother you? What are you willing to do to prevent it from happening?

Why don’t men do more to police other men rather than policing women? Why does a woman being raped still result in murmurs that she shouldn’t have been wearing such a skimpy outfit or shouldn’t have been walking alone after dark?

Many authors have previously discussed the fact that violence against minorities serves as a warning to the entire community that certain behaviors are not allowed, certain boundaries should not be crossed.

Many hate crimes are attempts to put minorities back “in their place” with the “place” often being more metaphorical than literal.

Violence against women has certainly served this purpose, reiterating that certain spaces “belong” to men and women enter them at their own peril.

Even as more and more women enter previously male-dominated spheres, most women will avoid venturing alone into city streets after dark (and those that do are often chastised for putting themselves at risk).

Violence against women — especially violence perpetrated by rapists, serial killers, and other misogynists — are hate crimes. The men who commit these acts often do hate women and they target women as a class, hating not a specific woman, but any and every woman.

So what can men do to about the violence against women?

In her June 2014 article, “35 Practical Steps Men Can Take To Support Feminism,” Pamela Clark suggests steps like giving women space (especially at night or while alone) and interjecting yourself into situations where a woman appears in distress while in the company of men.

Here are some other suggestions along the same lines.

- We can make sure women aren’t left alone in vulnerable situations.

- We can corral our friends if they seem to be heading toward victimizing someone.

- We can cut short any conversation that suggests committing violence against women.

- We can tell our friends how violence against women impacts all of us.

- We can support urban development that creates safe, lighted, and visible pathways with periodic emergency call boxes.

- We can support free public transportation so all women have a chance to get home without walking.

- We can support living wages, so that women are less likely to be forced into dangerous situations.

- Domestic violence is often linked to financial troubles within the home, perhaps because many men’s sense of self revolves around being good providers We can help working class men — disproportionately impacted by the economic downturn — gain full employment.

- But we can also work to help all men find reasons to feel good about ourselves that aren’t tied to our paychecks.

- And we need to cut short all of these arguments that currently suggest men are “losing” (status, wealth, position, power) and that women are to blame.

These are where we can start, but to really reduce violence, we must do more.

Because so many women are subjected to violence by their own partners, we must become self-policing.

- We must become aware of our own triggers and find ways to prevent arguments or bad days at work from resulting in our lashing out physically or emotionally.

- We must reduce our alcohol intake and substance abuse because imbibing in those substances reduces our self-control.

- We must evaluate our own thought processes and conversations and take steps to reduce our own misogynist thoughts and comments.

- We must become better at expressing our emotions, so that they aren’t bottled up inside of us to fester until we explode.

- We can avoid using statements that characterize women as “whores,” “bitches,” “sluts,” or “cunts.”

When Diane and I served as foster parents for adjudicated youth, we parented teenage boys, nearly all of whom had been arrested for perpetrating sexual violence. (Not surprisingly, many had also been victims of sexual violence.)

In the intensive 24/7 program that our boys were in, they learned to see women not as objects or people foreign to themselves but as thinking, feeling individuals with their own interests and emotions.

The boys were taught empathy and how to recognize and avoid their own triggers — including porn. Many of these youth offenders had consumed hours and hours of ultra-violent porn, which had led some of them to believe that women liked to be treated in those ways.

Based on what we learned in that program, here are a few other things that men can do to prevent violence against women.

- We can shut down misogynistic comments from our friends and acquaintances, knowing that violence against women often stems from hatred.

- Especially in all-male venues, we can stand up for feminism and ask other men to stop belittling women and slut shaming.

- We can support sports programs and other activities that channel the energies of young men into positive outlets.

- We can prevent underage viewers from accessing porn, especially those involving violent and rape scenarios.

- We can support mental health providers and work to eliminate the stigma against seeking psychological counseling. We shouldn’t always just “man up.” Sometimes we should seek the help of trained professionals.

***

All of these suggestions are just starting points. Eliminating violence against women is not easy, but it is necessary.

And it is a fight we can’t afford to lose.

Our very humanity may be at risk.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

With his wife Diane, Jacob Anderson-Minshall is the co-author of Queerly Beloved: A Love Story Across Genders the story of their 23-year relationship surviving the transition from lesbian couple to man and wife.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more