Recently, I had what felt like an awesome idea.

I had gone to bed at night, feeling really overwhelmed about how full I felt, about how bloated I was. And that, very quickly, translated in my eating disordered mind into “I ate too much.”

Whatever that means.

So as I lay there in my discomfort, trying to quiet the thoughts enough to fall asleep, I remembered something that soothed me: A few times, I’ve seen Tumblr posts that address this issue exactly – in the form of three-paneled pictures of women from side view angles showing how different their stomachs look upon waking, after lunch, and then after dinner.

The entire point of those posts is to normalize how our bellies grow and expand to hold food, to remind us that our bodies are wonderfully adaptive and take care of us.

And remembering that did, indeed, help me sleep.

And when I woke up in the morning, I thought it might be a good idea to do one of these memes, too. After all, sometimes when I’m feeling body-negative, the best thing I can do for myself is to be present in my body. And besides, maybe some other folks needed the reminder, too.

So I took the first picture, and then I posted on my social media that if anyone else wanted to join in, they were more than welcome to. I envisioned a magical influx of body positivity taking over my timelines, dashboards, and newsfeeds by nightfall.

And then I walked over to my (aptly named) vanity to do my makeup.

But while I was blending a blush called Fearless on my cheeks and smearing a lipstick called Anarchy on my lips (both, by the way, also aptly named), I had a sudden thought:

Wait a minute. What does a meme like this say about fat people? For one thing, they probably don’t have the visual experience of “food babies.” And for another, this meme can be interpreted as reassuring thin people that they’re not fat – just “normal.”

I put the lipstick down.

Fuck, I thought. That’s fatphobic as all hell.

And so I rushed to my computer to delete what I had written on social media – not to erase the mistake so much as to avoid spreading false body positivity – and there, I had already been approached by two women who I respect deeply, Cathy and Ivy, about whether or not this was a campaign that makes sense for fat women.

And, honestly, it doesn’t.

And if your attempt at eating disorder recovery advocacy isn’t empowering for fat people, then it’s not good enough.

And that isn’t to say that your activism isn’t necessary, isn’t appreciated, isn’t important. Anyone who does anything to push for eating disorder recovery is someone who we need in our collective community.

But as far as I can tell (and, trust me, I’m pretty involved in the movement), eating disorder recovery advocacy almost always excludes fat people from the conversation – and that’s a problem!

And since I’m always thinking of ways that we can improve the discourse around body positivity to be—well—more body-positive, I think it’s high time we make some simple, yet powerful changes to our body image activism so that we can work toward dismantling fat oppression within it.

So as you move forward championing for an eating disorder-free life (and congratulations, by the way, if you’ve chosen the path to recovery!), here are four questions to ask yourself to gauge whether or not your activism is fat-inclusive.

1. Are You Privileging Thinness?

Stop.

Wait a second.

Before you reblog yet another eating disorder recovery meme on Tumblr, ask yourself: What percentage of the pictures on my blog depict thin women?

Because I’m willing to bet that it’s, um, a lot. And that matters.

I’ll be honest: As a person with an eating disordered history, I don’t always actively think of myself as a thin person – because I don’t always feel that way. But in reality, I am.

And the way that that intersects with my eating disorder matters.

It matters because when I see Lifetime movies about eating disorders on TV, I frequently can identify with the body that I see represented there. It matters because when I watch pro-recovery mantras scroll across my Tumblr dashboard, they’re often overlaid against pictures of people who look like me. It matters because when I tell people I’ve had an eating disorder, they don’t scoff in disbelief.

My eating disorder is taken seriously, and my eating disorder is constantly validated by representations of what eating disorders look like.

That’s thin privilege.

And what, exactly, is thin privilege?

Well, luckily, I write about it all the time, so there are already resources on Everyday Feminism to help you address this.

But here’s a basic rundown: Thin people are privileged in our society because our cultural norms cater to thin bodies. Therefore, our lives are made somewhat easier because we hold power in this regard.

And if you, too, are thin, it’s important to notice that eating disorder awareness campaigns, as well as recovery advocacy, generally privilege you and your experience.

Now, it’s important to note here that not all people with eating disorders have thin privilege. Eating disorders can exist in any body, and body types are not hints toward diagnoses.

But for those of us who do exist at that intersection, it’s necessary to keep in mind that even though we’re marginalized by way of dealing with a mental health issue, those of us who are eating disordered and thin still experience thin privilege.

And one of the biggest mistakes that people with privilege make is not even realizing that their privilege exists, thereby exacerbating the related oppression.

Because having privilege means never having to think about your privilege.

But if you’re doing eating disorder recovery advocacy, it’s important that you think about it and actively work to overturn it.

So before you share on Facebook a video by yet another thin woman discussing eating disorders, ask yourself: “Am I privileging thinness? Am I also posting an equal amount of eating disorder stories from fat women, or body-positive images that depict fat bodies?”

And if not, start.

2. Does Your Activism Actively Deconstruct Fatphobia Alongside Eating Disorders?

Eating disorders are complicated.

They’re biopsychosocial in nature, which means that their onset is caused by some combination of our bodies, our brains, and our environments.

We have no control over our brain chemistry making us susceptible to an eating disorder, but the environment that we’re in can have a hugely profound effect on whether or not we actually develop one.

That is: While our brain chemistry may be predisposed to obsession/compulsion, our environment plays a role in what our brains obsess over or compulsively engage in.

And if we didn’t live in a culture so fixated on thinness and on diet control, maybe not so many people would find themselves with obsessions/compulsions fixated on food and weight – also known as eating disorders.

And what is diet culture rooted in, really?

Fatphobia.

There is an undeniable connection between living in a fatphobic society and the rise of eating disorders.

And if you want to fight against one, you really have no choice but to fight against the other, too. Because they have the same root cause – and that’s exactly what we need to attack.

That means that while talking (and constantly – please do talk about this constantly!) about eating disorder recovery is really important, your advocacy isn’t really complete if you’re not talking about fatphobia, too.

You need to address both.

You need to be fighting for the right for fat people to live their lives without shame, to be treated with dignity and respect, to be released from the diet industry stronghold.

You need to help people understand that most of what we think we know about obesity is wrong. You need to help people understand that it’s okay to be fat. You need to help people understand that this “But what about your health?” bullshit is nonsense.

And you really, really, really need to avoid spreading recovery memes that are inherently fat-shaming.

So, before you post, ask yourself: “Does this suggest that fatness is undesirable? Does this play along with society’s assertion that fat is bad and should be eliminated?”

And if so, scratch that.

Post something about fat acceptance instead.

3. Are You Focusing More on Body Issues or Food Issues?

In the world of mainstream body positivity – and by extension, eating disorder recovery advocacy – there are two main avenues to undoing the social scripts that we’ve learned: positive messages around food and positive messages around bodies.

Most of what we find, though, leans toward the latter a la problematic mantras like “Love Your Body” (umm, can I get an instruction manual?), “All Bodies Are Beautiful” (why are we still focused on beauty, again?), and “Real Women Have _____” (stop) – which do next-to-nothing to improve our relationships with our bodies.

And while some amazing people are actually putting work into helping us work through our complicated relationships with our bodies (check out Virgie Tovar’s Babecamp, Beauty Redefined’s program, and the upcoming documentary Fattitude), mostly, people are force feeding us one-size-fits-all body positivity that leaves us craving something more substantial.

And some of these messages are actually extremely detrimental in how clearly they privilege thinness – and therefore demonize fatness.

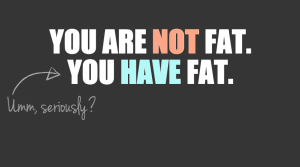

For example, one popularly shared concept is that of the “You’re Not Fat – You Have Fat” variety, which is often followed up with something along the lines of “You also have fingernails, but you are not ‘fingernail.’”

On the surface, this appears body positive in that it’s attempting to teach people – and in particular, women – not to talk engage in negative self-talk. But that, in turn, defines fat as negative and leaves anyone who actually is fat out of the conversation.

Similarly, the tongue-in-cheek assertion that “If you want to be skinny, just point to your skin and say, ‘I’m so skinny’” positions thinness as something toward which to strive.

And yet, I see posts like these posted in eating disorder recovery spaces constantly.

We either have attempts at body-positive messaging that are too broad to feel meaningful or too narrow to be inclusive.

So, instead, focus more on positive messaging around food.

Because not everyone who’s in eating disorder recovery looks the same, so not everyone can identify with these kinds of messages around bodies. But everyone who is in eating disorder recovery definitely can identify with food struggles.

That’s literally our only foolproof connection to one another: We all struggle with food to some degree.

Therefore, messages around making peace with food – so long as they make room for whatever that means for folks individually – can be more helpful.

And it’s important to note that common memes that deal with food issues – like “You need to eat,” “Starving doesn’t make you stronger,” and “Eat whatever you want” – often place restrictive eating disorders as the most common. And not only is this not true, but it also reinforces the eating disorder hierarchy, which we all know is dangerous.

So, simply, ask yourself: “Is this pushing an idea around bodies that might not apply to everyone’s journey? Or is it a message around creating a happier relationship with food?”

And try to post more of the latter.

4. And When in Doubt: Is This Relevant to Fat Folks?

This is the question that you should always come back to.

Before you reblog that artsy black-and-white photo of a thin white woman holding a piece of paper that reads “Start a revolution – stop hating your body…”

Before you post that video of yourself in a standard size bathing suit, letting people know that “If you want a bikini body, just put a bikini on your body…”

Before you decide to take part in a meme that normalizes thin women’s experiences with food babies…

Simply ask yourself “Would this be relevant to fat folks?”

And if not, then rethink it.

And this isn’t to say that we shouldn’t have safe spaces to talk about our own issues and unique struggles with our bodies. We should.

I think it’s fair for people with thin privilege to still be able to talk about their eating disordered experiences because I think that telling our stories is part of the road to healing.

And I also think it’s absolutely necessary for people without thin privilege to carve out opportunities to discuss their unique struggles at the intersection of fatphobia and mental health stigma.

But we – as a broader community – need to spend more time consciously thinking through who our messaging has the possibility to help.

And if we’re systemically leaving people out of our messaging, then we’re not only leaving them out of our support and compassion, but we’re also potentially leaving them out of recovery.

And while all eating disorder recovery advocacy is necessary, the fatphobic kind is not what we should be here for.

***

Special thanks to Louise Green, Joni Edelman, Amanda Trusty, Jen Mclellan, and Lindsey Averill for working with me on this piece. Your advice, your work, and your friendship mean everything to me.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Melissa A. Fabello, Co-Managing Editor of Everyday Feminism, is a sexuality educator, eating disorder and body image activist, and media literacy vlogger based out of Philadelphia. She enjoys rainy days, Jurassic Park, and the occasional Taylor Swift song and can be found on YouTube and Tumblr. She holds a B.S. in English Education from Boston University and an M.Ed. in Human Sexuality from Widener University. She is currently working on her PhD. She can be reached on Twitter @fyeahmfabello.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more