In recent years, the tech industry’s gender imbalance has become a frequent topic of discussion in the media, and people are starting to see how skewed the ratio really is.

About 19% of software engineers at 230 companies included in a crowd-sourced spreadsheet maintained by Pinterest software engineer Tracy Chou are women. According to another source, LinkedIn profiles, only 16% of software engineers and 9% of hardware engineers are women.

When you look at these numbers, you may be tempted to assume that women are less interested in or capable of working in technical roles. But those who jump to this conclusion usually haven’t experienced the hostility and discouragement that women in STEM fields face.

When we look at all of the cultural obstacles, biological explanations no longer seem necessary, and it becomes clear that those who explain away lack of diversity in tech with biology are part of the problem.

Rather, many studies have shown that work environment, company culture, and coworkers’ biases play huge roles in making women feel unwelcome. Girls also get the message that they’re not cut out for STEM fields before they even enter the workforce, starting with gendered toys and activities during childhood and spanning throughout their education.

In addition to research, I have personal experience with the unintentional ways tech companies leave women out.

I spent a year in Silicon Valley doing marketing for a tech startup and attending events involving other companies, and while I met many great people who are still my friends today, it also became obvious that most of these companies were created and run by white men with their own interests in mind, and the culture of Silicon Valley reflects this leadership (that HBO show isn’t too far off).

While no woman should feel pressure to work in tech just to balance out the ratio – I ultimately went down another career path based on my personal interests and feel good about it – a problem occurs when people who are interested don’t feel that the option is viable because of gender, race, sexuality, or any other facet of their identity.

From meet-ups for women in technology to coding programs for girls, a number of organizations are striving to rectify the tech industry’s gender imbalance. But what is causing this problem in the first place?

Here are some microaggressions that I, other women who have worked in tech, and research on gender discrimination have found keep women out of the tech industry.

1. Using Gendered Language When It Doesn’t Apply

In conversations and even in job descriptions, sometimes the pronoun “he” is used to describe engineers or managers by default. For example, this kind of conversation is common at networking events:

“I’ve heard of that company; my company’s CEO actually used to work there.”

“Oh, what’s his name?”

The assumption that an employee in a technical or executive role is male fails to acknowledge everything women have accomplished in the industry despite the obstacles. Though most CEOs and engineers are currently men, many are women as well.

In addition, companies can shoot themselves in the foot by using the pronoun “he” in job descriptions.

In one survey on what deters women from male-dominated professions, one popular answer was the wording on job postings, with one woman citing “his” and “him” as words that dissuaded her from applying.

2. Only Carrying Company Merchandise in Men’s Sizes

When I first joined my company, I got to choose a company T-shirt and sweatshirt from a selection of women’s sizes. I soon learned that this is a rare experience.

In fact, one of my female coworkers told me that the company only gave out men’s-sized shirts until a few of them put their foot down and demanded clothes that fit.

When I went to conferences, many participating companies handed out shirts, and they were all men’s sizes. I didn’t mind wearing them, but that’s probably because I’m used to it.

Imagine if, on the other hand, men were only offered shirts cut in women’s styles. There would be nothing wrong with wearing them, but it would make a lot of people uncomfortable.

3. Engaging in Locker Room Talk at Company Events

One night, during dinner with several coworkers, one male sales representative advised an intern that the best way to pick up women was to go to gay bars at the very end of the night, when the women there are “starved for male attention,” and “clean up.”

This conversation made me pretty uncomfortable.

While there’s nothing wrong with pursuing dates or sex at public venues like bars, my coworker’s suggestion that men accomplish this by exploiting women in gay bars’ supposedly low self-esteem didn’t sit well with me.

Actually, it sounded a bit like the pickup artist tactic of negging – making a woman feel bad about herself so that she’ll turn to you for validation.

While not everyone at my company was like this, the “brogrammer” – a nerdier variation of the stereotypical frat boy – is alive and well in Silicon Valley.

One male engineer at another company told me that his manager once encouraged him to hit on female colleagues at a diversity-oriented company event.

When we create an environment where it’s okay to objectify women, we detract from the work women are doing and teach them that their contributions are not as valuable as their male coworkers’.

4. Dismissing People Who Try to Call Out Sexism

On this same night, when I pointed out that my coworker’s pickup tactic sounded kind of manipulative, I got a collective “Come on, Suzannah” from both the men in the conversation and even one woman. I felt like a party pooper.

Afterward, when those two men went to a bar and invited the rest of us along, I declined to join them. I didn’t feel they’d welcome the company of someone trying to stifle their fun.

A few days later, I brought the incident up with a manager who was particularly interested in workplace diversity. He was bothered by the pickup artistry, but even more bothered by the dismissal I received when I called it out.

Because my coworkers made me feel like I’d done something wrong, I was now extremely hesitant to bring up diversity issues again.

I shouldn’t have needed a man to tell me I’d been gaslighted, but his response – rather than “come on” – exemplifies how people should react to employees who call out sexism and other forms of discrimination.

5. Devaluing Woman-Dominated Job Positions

During orientation on my first day of work, the HR manager warned me that a lot of my coworkers were super smart and reassured me that it I didn’t have to feel intimidated. Similarly, at a happy hour with another company, their HR manager asked me how I deal with all the “geniuses” I worked with.

In both situations, I wanted to say that I’m not intimidated by smart people because I’m one of them.

I wanted to point out that convincingly ghostwriting articles on behalf of executives who have built complex software and sounding like an expert on the topic can require just as much intelligence as building the technology.

I let it go because I knew their hearts were in the right place and didn’t want to cause conflict, but maybe I should have said something. HR employees play an important role in shaping employees’ views of one another – a role that is also overlooked because it is non-technical.

These colleagues (both women) assumed that I wouldn’t consider my intelligence on par with those in technical roles, not because I was a woman per say, but because I was on the marketing team.

However, this team consisted entirely of women, while the company’s C-level executives were all male and the engineers were three-quarters male. This is a common breakdown at tech companies, which is why marketing has been called a “pink-collar” profession.

No doubt, many of the men I worked with were brilliant, but so was the female product marketing manager who drew diagrams to illustrate everything from big data analytics to startup funding rounds, and so was the PR agent who crafted pitches that drew in writers from major business journals.

By neglecting the intelligence required for roles like marketing, PR, sales, and HR, we end up underestimating women’s intelligence as well.

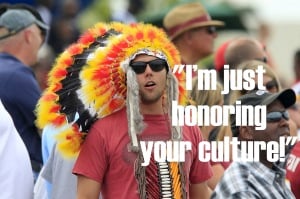

6. Failing to Compensate for Implicit Biases

Studies have shown that, even when coworkers have no intention of discriminating, gender often affects hiring decisions and treatment in the workplace.

For example, one part of a resume known to sway hiring managers is the name. One study found that scientists were more likely to hire someone for a lab manager position when the name on the application was “John” than when the exact same resume had “Jennifer” at the top. In addition, they said they’d pay Jennifer $4,000 less per year than John.

This bias is hard to rectify by sheer will because it’s subconscious, so perhaps companies should actively compensate for it by removing names from resumes during initial screenings.

The gender of the candidate is revealed during the interview, however, so some companies address this issue by interviewing a set number of women for every position and making sure women are giving at least some of the interviews.

***

As these microaggressions demonstrate, making women feel welcome in the tech industry and other fields where they’re marginalized is about more than just not being sexist.

Most leaders of tech companies want to use all the talent available to them regardless of gender, for selfish reasons if nothing else.

But it’s not enough to want more women at your company. People need to be aware of how women will perceive actions they may not normally think about.

The good news is that recruiting a more diverse team can give women greater influence over a company’s culture, instigating a self-perpetuating cycle. But companies that were founded by cis, straight, white men have an uphill battle ahead of them.

So, if you’re thinking of creating a startup, it’s best to start off with a diverse founding team from the get-go.

If that’s not possible, make sure to solicit the input of people who are targets of discrimination in the industry – because some of the most insidious obstacles aren’t obvious to those they don’t directly affect.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Suzannah Weiss is a New York-based writer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Salon, Seventeen, Buzzfeed, The Huffington Post, Bustle, and more. She holds degrees in Gender and Sexuality Studies, Modern Culture and Media, and Cognitive Neuroscience from Brown University. You can follow her on Twitter @suzannahweiss.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more