Source: CDC

It’s important that when talking about Indigenous justice, we talk in specifics because of how colonization has impacted different Indigenous people in varied ways.

This article will focus on the context of colonization in what we now refer to as the United States, and it is informed by the activism and expertise of one Dakota person, Waziyatawin, Ph.D.

Thus, while there are surely ways that this article can inform activism outside of this context, it should be understood to be limited in this way.

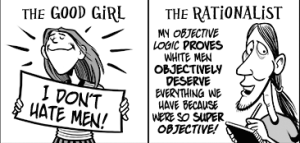

In their seminal work linking Critical Race Theory to education entitled Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education, Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings and Dr. William F. Tate, IV explain how the United States is founded fundamentally on property rights rather than human rights.

If human rights were central to the constitution (rather than property rights), it would have been far more difficult for European colonists to continually legally justify slavery, genocide, and the theft of virtually every acre of land in North America.

Thus, the mark of success in the US constitutional system is ownership of property. Whether we’re talking abstract “assets” like stock, the ownership of people, or ownership of land, the longest-running “smart investment” for those legally and financially able to access it, property, drives wealth and prosperity in the US and most Western, capitalist societies.

As a result, any conversation about Indigenous justice threatens the positionality of all settlers — non-Indigenous people — because, in the words of Dr. Wazayatawin, “[W]ithin Indigenous worldviews, land is life. Colonization, in its fundamental sense, involved disconnecting [Indigenous people] from our homelands (so our homelands could be occupied by settlers instead).”

And in my experience, any time we start talking about land return or reparations, White folks (those settlers like myself for whom this property-based system was built) collectively freak out.

If we’re going to talk about what justice actually can and must look like, we have to start talking about the decentering of settler identities and people and about the recentering of Indigenous people and struggle — no matter how uncomfortable that may make us.

So Who Are Settlers?

If we’re going to have a conversation about what justice can actually look like, though, we need to be precise with our language.

One of the countless things I appreciate about Dr. Waziyatawin in her scholarship and activism is that she reminds us of an important distinction within very language.

Indigenous people are notably different from other oppressed people in the United States in that they are simultaneously colonized and oppressed.

As Dr. Waziyatawin puts it, “Colonization is always a form of oppression, but oppression is not always colonization… a population must have a land-base before it can be colonized.”

And that distinction is vital.

It’s not to take anything away from the distinct oppressions of settlers of Color, and surely those stolen from their lands and sold into slavery come from colonized lands and have lost their land-base in that process. But this distinction makes one thing clear: The system of colonization in which we live was built for White people, and White people are privileged above all and benefit form that system.

To understand positionality, though, is to understand, in Dr. Waziyatawin’s words, that “there are certainly varying degrees of culpability and poor, landless, oppressed people of Color have not benefitted to the same extent that White, wealthy landowners have. And, those who have come as slaves, through sex-trafficking, etc. cannot be held responsible for their presence on Indigenous lands. But free populations, even oppressed ones, are settlers on someone else’s land.”

Thus, if we are ever going to realize true anti-colonial racial and class justice, we have to understand our positionality and collaborate accountably across difference toward Indigenous liberation.

What Can White Settlers Do to Help Realize Indigenous Justice?

Notably, as the author of this piece, I am a White settler. It is not, nor should it be, my position to tell Indigenous people or settlers of Color how to engage in work for justice.

Thus, while that conversation can and should take place in coalitions of people of Color, from here forward, I will be offering suggestions, as informed by Dr. Waziyatawin, for how White settlers can work for justice.

For those of us who consider ourselves progressive, it’s not enough to, as Andrea Smith puts it in Conquest, “bemoan the genocide of Native peoples” while “implicitly [sanctioning] it by refusing to question the legitimacy of the settler nation responsible for this genocide.”

We have to act — and in doing so, we have to risk something.

1. Listen To and Call Other White Settlers to Listen to Indigenous Truth Telling

In her book What Does Justice Look Like? The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland, Dr. Waziyatawin devotes an entire chapter to the importance of Indigenous truth telling, noting “for those of us who believe in the transformative potential of education, our hope derives from the expectation that once people understand the truth, they will be compelled to act more justly.”

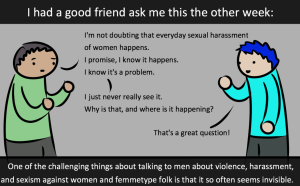

Sadly, though, both research and the lived experience of many marginalized and oppressed people tells us this is not quite the way things work.

In our interview, Dr. Waziyatawin even noted how her views on the role of truth telling have evolved. Particularly when people are vehemently opposed to learning a truth, truth telling can simply leave oppressed people open, vulnerable, and hurting while those of us with privilege can walk away, more resolved in our ignorance.

But that does not mean that truth telling has no place in working for justice.

For those of us striving for an accountable solidarity as settlers, acknowledging, reflecting upon, and then acting from the truths of Indigenous people are vital first steps in working for justice.

As Dr. Waziyatawin puts it, “There is righteousness and strength to be found in truth telling, as well as guidance and direction.”

2. Support and Donate Money or Land to Indigenous Land Return Efforts

There’s no way around it. Indigenous justice means land return.

Of course, it means more than that, and there are complex and nuanced views among different Indigenous people about what land return can look like, but if we are ever going to realize justice, land return must be central to that justice.

Does that mean you have to immediately donate your home to the nearest Native tribe? No, not unless that’s what you feel called to do.

But land return can look all kinds of ways.

Returning public land, like state and national parks, is a fantastic place to start and has been called for by many Indigenous groups for many years. It was even called for by the United Nations as recently as 2012.

This does not require individual settlers to give up their personal property in order to take steps toward justice. Further, the United States government, as the nation responsible for genocide, has a responsibility to pay reparations in the form of land return.

While not all Indigenous people call for or want immediate national park land return, a simple thing we, as White settlers, can do is to support those who do.

However, it’s also important that we give of our own assets to contribute to Indigenous land return because we literally profit from our “possessive investment” in colonial Whiteness.

Dr. Waziyatawin says, “When settlers contribute to land buy-back for Indigenous populations, they are participating in an act of personal reparative justice. Their actions demonstrate that they both recognize the gross injustices perpetrated against Indigenous people and that they are willing to actually sacrifice something to attempt to right colonial wrongs.”

It is also important that we be willing to give more than what is comfortable to decolonization efforts like these.

To give what is comfortable doesn’t challenge us, so it isn’t, in fact, a sacrifice. To give an amount that stretches us, though, can be transformative. So when we give, we should be giving an amount that makes us pause and ask, “Is this something I can really afford?”

If you don’t have much in the way of money yourself or you want to maximize your efforts, consider hosting a fundraiser with friends or family!

It’s important, though, that it be settler money that is used to buy back land, for it only reifies colonization when “Indigenous lands are stolen and commodified and then sold back piecemeal to the colonized — at least to the few who have maneuvered through the capitalist system enough to muster the cash to restore a few acres,” said Dr. Waziyatawin.

Want to donate right now to land return? Do it!

You can donate right now to the Makoce Ikikcupi (Land Recovery) project through the nonprofit Oyate Nipi Kte (The People Shall Live), an organization founded by Waziyatawin, Harlan LaFontaine, and Janice Bad Moccasin! Please do! You can also donate to Oyate Nipi Kte’s other decolonization efforts, including culture and language preservation, through their site.

3. Abdicate Time and Space to Indigenous People and Issues in Your Intersectional Social Justice Work

Knowing that we live and work all in the context of Indigenous genocide and land theft, one of the simplest things we can do is to center Indigenous people and issues in our work for justice.

A simple place to start is to acknowledge that we are doing this work on occupied Indigenous land.

Having a gathering or conference not explicitly focused on Indigenous issues? Start the conference by acknowledging this fact. If you have relationships with Indigenous tribes in the area, invite a local elder to speak.

More than in any other “progressive” work, I feel like this is important for White-dominated environmental movements.

First, Indigenous people have been leading environmental justice movements since White settlers first set foot in North America, yet their work often gets devalued because it doesn’t look the way that White environmentalists want it to look.

Second, modern society is fundamentally unsustainable and when we acknowledge that, we must look for alternatives. When the land, air, and water are central to Indigenous justice, Indigenous leadership offers powerful solutions.

Dr. Waziyatawin says, “The best alternatives will be those that have already been tried and tested over thousands of years — those of Indigenous Peoples who have a demonstrated history of sustainability on this continent.”

Thus, if we call our movements intersectional, but do not center Indigenous struggle (which necessitates decentering Whiteness), then we need to do better.

4. Stop Treating Indigenous Genocide and Settler Violence as Things of the Past

One of the most destructive patterns that avidly racist and well-meaning White settlers both commit is the modern erasure of Native people and struggles. So often, we treat Native people and the injustices they face as “noble” relics of the past.

Ain’t nothing quite like a White person derailing a conversation about justice with “Well, it’s not like I or my parents killed any Indians! Yet you want me to sacrifice?”

In our interview together, Waziyatawin described this as the single thing she most wishes people would take away from this article, noting, “While some policies and practices were institutionalized centuries ago, Indigenous people are still experiencing oppression from them.”

The very fact that so few Indigenous people live on their ancestral lands and have access to holy sites is violence, but we needn’t stop there.

The Indigenous unemployment rate off of reservations is twice that of White settlers, and on reservations, it can near 50%. Economic justice is Indigenous justice.

Indigenous children are stolen from their families and placed in (often White) foster care at epidemic levels. Reproductive and family justice is Indigenous justice.

Indigenous people have some of the worst access to quality health care and worst health care outcomes of anyone in what we refer to as the United States. Health justice is Indigenous justice.

In all of the talk about police violence in our society today, Indigenous people are those most likely to be killed by police of any racial group. Police accountability and incarceration justice is Indigenous justice.

Sadly, I could do this all day, but the point is simple: When we speak of Indigenous people and their struggles for justice as relics of the past, we erase oppression.

So we need to act.

To close with words from Dr. Waziyatawin, Indigenous justice “may, at first glance, seem too large an issue to try to tackle, but I would encourage people not to become immobilized. Instead, seek concrete ways that injustices can be addressed. Please, no more symbolic gestures.”

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Waziyatawin is a Dakota writer, teacher, and activist from the Pezihutazizi Otunwe (Yellow Medicine Village) in southwestern Minnesota. She is committed to the pursuit of Indigenous liberation and the protection and reclamation of Indigenous homelands and ways of being. She earned her PhD in American history from Cornell University and has held tenured positions at Arizona State University and the University of Victoria where she also held the Indigenous Peoples Research Chair in the Indigenous Governance Program. In 2008 Waziyatawin founded the nonprofit Oyate Nipi Kte (The People Shall Live) and continues to work with their Makoce Ikikcupi (Land Recovery) project. She is the author or co/editor of six volumes, including the recently co-edited volume with Michael Yellow Bird entitled For Indigenous Minds Only: A Decolonization Handbook (SAR Press, 2012). She lives in her home community in the beautiful Minnesota River Valley.

Waziyatawin is a Dakota writer, teacher, and activist from the Pezihutazizi Otunwe (Yellow Medicine Village) in southwestern Minnesota. She is committed to the pursuit of Indigenous liberation and the protection and reclamation of Indigenous homelands and ways of being. She earned her PhD in American history from Cornell University and has held tenured positions at Arizona State University and the University of Victoria where she also held the Indigenous Peoples Research Chair in the Indigenous Governance Program. In 2008 Waziyatawin founded the nonprofit Oyate Nipi Kte (The People Shall Live) and continues to work with their Makoce Ikikcupi (Land Recovery) project. She is the author or co/editor of six volumes, including the recently co-edited volume with Michael Yellow Bird entitled For Indigenous Minds Only: A Decolonization Handbook (SAR Press, 2012). She lives in her home community in the beautiful Minnesota River Valley.

Much of this article is based on an interview conducted by the author with Wazayatawin in September and October 2014.

Jamie Utt is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is the Founder and Director of Education at CivilSchools, a comprehensive bullying prevention program, a diversity and inclusion consultant, and sexual violence prevention educator based in Tucson, AZ. He is currently working toward his PhD in Teaching, Learning, and Sociocultural Studies at the University of Arizona with research interests in the role that White teacher’s racial identity plays in their teaching practice. Learn more about his work at his website here and follow him on Twitter @utt_jamie. Read his articles here and book him for speaking engagements.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more