Source: Huffington Post

Trigger Warning: This article contains detailed descriptions of intimate partner violence, including physical assault, sexual assault, and victim-blaming.

It’s not uncommon for an intimate partner violence (IPV) survivor to be asked, rather pointedly, “why they stayed.” And it isn’t okay.

When video surfaced of Janay Rice being knocked out by her then-fiancée/now-husband, Ray Rice of the Baltimore Ravens, questions swirled about “why she stayed.”

Many people asked, why would someone marry a man, after all, who punched them out in an elevator, then dragged their body out of it?

The graphic footage, which should have elicited sympathy for all that Janay Rice had been through, ended up just causing more humiliation for her as she was put in the spotlight across media channels.

Instead of her abusive husband’s behavior being condemned, hers was.

Her act of staying confounded folks, and even sparked a conversation on Twitter with the hashtag #WhyIStayed.

What that conversation illuminated was how problematic that question is — and why its answers are more complex than most people understand.

Asking a survivor of intimate partner violence “why they stayed” puts the onus on them to prove that their choices were valid and to explain their own abuse.

Leaving and staying aren’t the factors that cause abusive behavior; abusive behavior causes abusive behavior.

Asking why someone stayed in a violent relationship is akin to asking a sexual violence survivor why they let themselves be assaulted; the underlying question there is “If it was so bad, why didn’t you make it stop?”

The answer, when you put it that way, is vividly clear: Because survivors can’t make abusive behavior go away, and it shouldn’t be their responsibility to try to make it stop.

There are a myriad of reasons why IPV survivors stay in their relationships because there are a myriad of ways that a relationship with an abusive partner can look and feel.

No story of abuse is like the other, and there is no “correct answer” for a survivor of abuse to the infamous question of “why they stayed.”

To pretend that ending a relationship with an abusive partner is a matter of packing up and leaving is an act of willful ignorance, and it’s one that we as a culture need to abandon if we ever expect to shift our society toward embracing and supporting survivors instead of shaming them.

These are six reasons why survivors of intimate partner violence might stay in their relationships. They’re obviously not the only ones, but many other factors will fall into these broad categories.

Next time you want to ask someone why they stayed, remember these – and remember that it isn’t that simple.

1. Because the Cycle of Abuse Lets Survivors Hope for Change

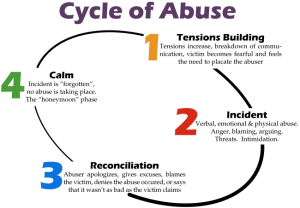

Lenore E. Walker — psychologist, founder of the Domestic Violence Institute, and author of The Battered Woman — created a now commonly used tool for understanding a relationship with an abusive partner called the “cycle of abuse.”

After interviewing 1,500 women who had been in relationships with an abusive partner, she discovered patterns in their experiences and broke them down into four broader stages: Tension Building, Acting Out, Honeymoon, and Calm.

Source: Soul Shepherding

During the Tension Building stage, a relationship between two people becomes stressed. The next phase, Acting Out, is marked by physical and emotional abuse, threats, and other altercations between the abuser and survivor.

In the Honeymoon phase, the abuser will apologize or otherwise make it seem as if the abuse won’t happen again. This leads into the Calm phse, where couples stay until more tension builds.

The Honeymoon and Calm phases eventually get shorter and shorter as abuse becomes more routine, ultimately leaving the survivor trapped in an escalated situation with very little control or a plan for a course of action.

The cycle of abuse can make it difficult for a survivor to recognize abuse as a pattern.

Their interactions with their partner during the Honeymoon and Calm phases may be loving, kind, and affectionate, or at the very least, are not marked by violence.

This can cause survivors to explain their abuse away as a one-time thing, a random occurrence, or a “rough patch.”

A woman with an abusive partner may even rationalize her abuse, blaming herself in order to maintain her mental image of her husband as her protector and lover.

Seeing abuse as a child or surviving a relationship with an abusive partner may also skew a person’s ability to recognize an abusive relationship or leave them with persistent feelings of worthlessness or low self-esteem, making them susceptible to further abuse.

The cycle of abuse also makes it possible for survivors to hope that their relationship will change.

When someone is invested in a relationship, cultural messages, social pressure, and even the opinions of their friends and family may lead them to stay and try to “fix” a relationship with an abusive partner.

Recognizing a pattern of abuse may not happen for a survivor until the cycle has already played itself out over and over again.

By the time a survivor comes to identify as such, or begins to recognize abusive behavior, their abuser may have already cut them off from their loved ones or otherwise isolated them from support systems necessary to leave.

And even if they have those things, when they come to realize they’re in a relationship with an abusive partner that won’t change, other factors can keep them there.

Remember that an abusive partner may not be actively causing pain all of the time, and a survivor – like anyone else invested in a relationship – wants to see the good in their partner.

Knowing that their abusive partner can make them feel good and safe is a powerful magnet that keeps them in the relationship.

They’re often anchored there by the hope that that person they fell in love with – the sweet, gentle, and caring one – will prevail over the person causing them harm.

2. Because a Survivor May Be Dependent on Their Abusive Partner

Leaving an abusive partner can be, in its own way, an act of privilege.

For many survivors, their economic or social well being may be on the line in walking away from their abuser.

For example, an immigrant woman may be abused by her husband, but rely on him for her ultimate standing as an American citizen or to prevent her own deportation.

An abusive woman might be the breadwinner in her home, and her girlfriend might lack job experience, practical skills, an education, or a separate savings account to live off of without her.

A man might abuse his husband, but have high standing in his community, putting his partner at risk for retaliation at work or in their social circle for leaving.

A trans woman may feel isolated in her relationship with an abusive partner because she lives in an area where the available resources – and her community – don’t affirm her identity.

Situations like these, and variations of them, aren’t uncommon in relationships with abusive people, which thrive because of power balances that leave abusers in the position to control and manipulate their partners.

Survivors often believe that they cannot survive or thrive without their abuser, and abusers often repeat this message to them in order to maintain control.

When someone plans to leave an abusive partner, they may have to consider money, their support system, shelter, and the sheer terror of starting over again before they’re ready.

And for some survivors, those factors will hold them back.

3. Because Leaving Can Mean More Violence

Many abusive partners will levy threats of further and more extreme violence against their partners as a way to stop them from reporting violence or leaving a relationship.

In fact, the moment when a victim of IPV leaves is the moment in their relationship when they are most likely to be killed.

For survivors, walking away isn’t always easy; it can be a decision that puts them in extreme danger.

Abusive people – who will almost unilaterally be in the position of power in a relationship economically, socially, and in other ways – keep their partners under their control by manipulating them with threats to keep them hopeless.

Once a survivor begins to stand up for themselves or recognize their relationship as abusive, an abusive partner who fears reproach from the police or simply wishes to maintain their abusive pattern with someone will do all they can to prevent that person from leaving.

For many survivors of intimate partner violence, staying and leaving are equally dangerous options.

4. Because of Their Children

Survivors of abuse who have children have to take them into account when they plan a course of action, and their children may ultimately be the reason they stay.

This could be because they think leaving will leave their child worse off or, in some cases, because they could lose those children completely.

Some abusive partners will harm or threaten to harm their partner’s children – even if those children are also their own – if a survivor reports their abuser to the authorities or confesses their experiences to someone they trust.

Survivors might also believe that it’s better for their children to have a father or mother in their life than to be raised by a single parent, and might stay to create a façade of stability for their kids.

For some, leaving an abusive partner could also mean a heated custody battle for their children.

Survivors in queer relationships may have gained legal custody over their children during a relationship, but not be their biological parent, and thus might fear losing contact with them in the event of a divorce.

For someone with little financial or social resources, they may be seen as an unfit parent by a court and lose their children to their abuser or Social Services.

Some people may also stay because they worry that leaving will further traumatize their children by making them witnesses to a messy divorce or even the imprisonment of their other parent.

5. Because Survivors of Violence Often Lack Support

We don’t live in a culture that believes survivors.

In the media, in our justice system, and in our social culture, people who come forward to say that they were abused or victimized by someone else face scrutiny, retaliation, stigma, and isolation.

Survivors might not be supported by their friends and family, their local police, or a judge or jury when they attempt to seek justice and out their abuser.

Intimate partner violence proceedings and legal systems meant to protect survivors of abuse fail them regularly.

Emotional abuse may not be taken seriously in court, and police officers who intervene in domestic disputes often ask survivors in front of their partners whether or not they’re being abused (a faulty strategy, considering the risks we just went over).

Some people who report violence to the police have also been abused when the officers came to investigate, further traumatizing them and leaving them with no real recourse.

And in our society, abusers who claim that their partners somehow “deserved” or otherwise warranted violence can find judges, trusted community figures, and police officers who will agree with them.

Survivors also face stigma when they come forward.

For intimate partner violence survivors of certain classes or social statuses, reporting abuse may be unseemly; for some, speaking up about abuse means speaking out against someone popular and loved in their community, and thus it means facing stigma and criticism.

(A harsh reminder is how our society has treated the women coming forward about being drugged and raped by Bill Cosby: ignored, criticized and made fun of, and ultimately shamed for daring to tell the truth about a beloved cultural icon.)

Abusers also might isolate their partners from their social support networks, leaving survivors on their own should they choose to leave.

Social pressures from friends and family to maintain a “happy marriage” or “work for a relationship” could similarly stop survivors from taking action against their abusers.

Until we create a culture where survivors are supported and believed when they come forward, the option could seem hopeless for survivors wondering how to get justice.

6. Because They Love Their Abusive Partners

Intimate partner violence is unique because it occurs in a relationship, and relationships themselves are complex beasts.

Fighting with your partner is not necessarily unusual or unhealthy, and neither are heated disagreements or arguments with someone you love.

For many survivors of violent relationships, abuse begins after trust – and love – has been established,

Entire years can go by in a relationship before an abuser shows their true colors and begins acting out.

Love is an intense emotion to detach from, and we may fall in love with abusive people.

Leaving someone you love, even when they’re treating you badly, is not easy. Leaving someone you love, even when being with them hurts, can seem harder than simply suffering through abuse.

Many people are still in love with their abusive people when they leave, and some stay because they believe only they can help their abuser transform.

For a survivor who loves and trusts their partner, abuse can seem like a “problem we should work through,” rather than a problematic behavior that needs to stop immediately.

In love, many things are far from “simple,” and many couples go through things together that don’t seem clear-cut or “black and white.”

Abuse can be, and frequently is, one of those things.

***

Empowering survivors of intimate partner violence is not something we can do by asking them why they stayed.

Being there for a survivor of relationship violence – be it by listening, asking if they need help, or letting them trust you with their stories – shows them that they are supported.

It can also help them break free from the shame and stigma of their experience rather than making them feel as if they’ve failed to do enough to “deserve” to be believed or empathized with.

Asking someone “why they stayed” sends a message to them that we know better. But, as these six reasons alone show us, often we don’t know the full story at all.

You can find resources at www.thehotline.org or by calling 1-800-799-7233 if you or someone you know is in a relationship with an abusive partner.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Carmen Rios is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She splits her time disparately between feminist rabble-rousing, writing, public speaking, and flower-picking. A professional feminist by day and overemotional writer by night, Carmen is currently Communications Coordinator at the Feminist Majority Foundation and the Feminism and Community Editor at Autostraddle. You can follow her on Twitter @carmenriosss and Tumblr to learn more about her feelings. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more