Source: Unsplash

Cisgender. Transgender. Genderqueer. Non-binary. Agender. Genderfluid. Demigender.

It seems like every day there is a new term to describe the countless different ways that people experience (or don’t experience) gender. This is because society is more and more being forced to deal with the reality that gender is more complicated than many of us were conditioned to believe.

This is a great development. There aren’t only men and women and gender can’t always be determined at birth.

Our expanding language is proof that people are also trying to expand their minds and accept more folks for who they are.

This doesn’t change the fact that it’s hard to keep up with all there is to be understood about gender. A lot of us have lived for decades thinking of gender a certain way, and have had much less time to fully understand all of the experiences lived outside of that way and what they mean.

This is a difficulty for even those of us who are not cisgender or who are familiar with contemporary queer a/gender terms — and can sometimes cause the way we interact with one another to be harmful.

Most of us, non-binary or not, grow up learning that men develop certain features. Many will grow facial hair. Their voices will deepen. They have a specific set of genitalia.

All of those things apply to me.

Yet the male gender doesn’t fit me for a variety of reasons, the least of which being that I don’t feel as if I share any particular set of experiences (or, more specifically, any particular interpretation of those experiences) with all men. I’m a Black non-binary person who was assigned male at birth.

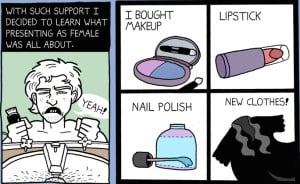

While I know that I am not a man, I don’t go out of my way to present in any particular way other than what makes me feel best in the moment.

I like the way nail polish, eyeliner, certain lip shades, and many clothes from the “women’s section” look on me, but if the average person weren’t to know any better they’d probably assume I was a man who enjoys wearing female attire and cosmetics, at most.

Because of this and my ability to seemingly easily remove that attire and cosmetics (dressing the part for work and other heteronormative activities is always more of a draining experience than others might think), I get all of the benefits of being able to “pass” as a cisgender man.

Those benefits are very real, and need to be acknowledged, but they do not change reality.

Even with all of those benefits, it’s still hard to feel as though I must constantly correct people about who I am or they won’t acknowledge my existence.

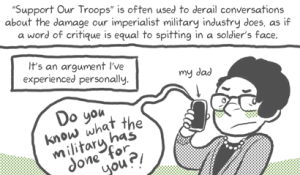

I still feel pressures not to express myself the way I need to express myself for fear of retribution because people expect certain things from me based on the gender they perceive me to be.

As many non-binary people know, the gender binary (the idea that there are just men and women) can feel like a cage. That cage does not disappear just because I “pass” more often than another non-binary person, and yet there are many people who understand that there is more than just the binary who are willing to deny the existence of non-binary people who can “pass” or who aren’t always bending gender enough for their standards.

A lot of this comes from a good place. People who can “pass” don’t experience the same types of violence that non-binary people who can’t might experience. But it’s important to realize that we can acknowledge this while still affirming people for whom they are.

Here are four reasons why.

1. How We Determine What Gender “Looks” Like is Often Arbitrary

What “look” makes a man a man? His facial hair? What about Hanaam Kour, the female model who proudly sports a beard that would make any beard lover (such as myself) swoon?

Is it a specific type of muscular physique? How do you account for female body builders who put most of the guys who go to my gym to shame?

Breasts and sexual organs? If you are conscious of transgender or intersex identities, or acknowledge medically necessary surgeries, you know this not to be the case.

Hormones, chromosomes, genitalia, bodily history and psychology can interact in endless ways to create so many different gender expressions, sometimes with one of those things having more influence than the others. Those things can correspond to a certain look, but they can just as easily not.

Yet, for non-binary people, we often don’t give the same room for their existence to defy that gender has a certain “look” that we may to others.

The truth is the way gender “looks,” just like gender, is on a spectrum, and the cut offs we apply are often arbitrary.

Yes, we can take a bunch of different physical attributes together and make an educated guess, but even those of us with a very minimal understand of gender would think to apologize to a cisgender person for mistaking their gender based on appearance. Non-binary people deserve the same respect.

Cisgender women who can “pass” for cisgender men also retain the benefits of passing in this way, but that doesn’t make them any less of a woman or make the refusal to acknowledge who they are any less damaging.

“Passing” is not as simple as being just a privilege because it is also an erasure of oneself.

Believing that gender has a “look” that is anything more than an educated guess is not only harmful for non-binary people, but for all people.

2. Limiting Gender to What it “Looks Like” is a Part of the Oppressive Function of the Gender Binary

As non-binary folks and people who understand the limitation of the gender binary, we already have an understanding that limiting gender to physical things, usually genitalia, is oppressive to people outside the binary.

To say that someone who was assigned a gender at birth because of how they look can only ever be that gender denies so many people the chance to actualize themselves. All the same, a lot of us are content to limit gender to other physical things even less central to one’s being, like clothes or hair.

Often this is because we rightly understand that gender is also a performance, not just an identity.

However, we need to be open to the fact that gender can be performed in different ways by different people in different scenarios, or we are no better than those who say gender is constricted to what you are designated at birth.

I am not always aligned so obviously with the normative presentation of maleness as I am at work. Without the pressures to maintain some type of living free of harassment and/or the fear of being let go, the “look” of my gender usually becomes more fluid.

But I always feel that fluidity, even when I am forced not to translate that feeling into an obvious look.

Who is to say that this feeling which never goes away is less valid than how others might perceive me on a given work day?

Thinking according to the gender binary means believing people who have certain physical features must be a certain gender, which is exactly what is done when we expect non-binary people to “look” a certain way. Gender is so much more than physical features, and performances can also be speech, movement, and other responses to the world.

We owe it to ourselves to allow gender its full possibilities, even if we know that some possibilities allow different types of violence than others.

3. Gender “Looks” Different Across Race, and Especially Outside of Whiteness

One of the most important things to remember about gender is that much of our current western perception of it is rooted in ideas stemming from European colonization. Many pre-colonial cultures and even modern-day non-white communities understand what we call gender outside of the male-female binary, and especially outside of what it “looks” like.

This means that what works for white people and gender may not apply to other folks, and is why I am a proponent of always mentioning race with gender.

A very obvious example is clothing that might look like a dress in our eyes or actions such as painting one’s lips not being designated to women only in places around the world. Those cultural practices have informed how non-white communities interact with gender even to this day, proving that the limited way in which we believe a man or woman “looks” a certain way is very much a product of white supremacy.

Further, this concept of gender was not meant for the benefit of non-white people, especially Black folks, so to force it onto us based on looks alone is often an act of racism.

I like to tell the story of the white person who told me I was taking up space by claiming my place outside of the binary while that person still perceived me to be a man. It’s interesting how this was framed in terms of “space,” seeing as this space for gender was taken, named, and shaped for white people.

I intend to take as much of it back as possible, and in doing so, reject ideas about what gender looks like that are rooted in whiteness.

***

While it’s critically important to recognize and understand that looking the part within this gendered society will make certain aspects of life much easier (getting and retaining a job, for instance), if we are to reject the gender binary as a ruling construct we have to add nuance to everything that seems to make gender easy (is it healthy for non-binary people to force themselves into heteronormative roles every day?).

Gender is not easy. It’s complicated, and that means the way people move within or outside of it can always be more complicated than it looks.

Non-binary people who “look” a certain way can achieve certain things that those who don’t look that way can’t, but that doesn’t make them any less non-binary.

It makes the world that is doing the looking mistaken. We all need to ask ourselves: am I a part of that world?

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Hari Ziyad is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a Brooklyn-based storyteller. They are the Editor in Chief of RaceBaitR, a space dedicated to imagining and working toward a world outside of the white supremacist cisheteropatriarchal capitalistic gaze, and their work has been featured on Gawker, The Guardian, Out, Ebony, Mic, Colorlines, Paste Magazine, Black Girl Dangerous, Young Colored and Angry, The Feminist Wire, and The Each Other Project. They are also an assistant editor for Vinyl Poetry & Prose. You can find them (mostly) ignoring racists on Twitter @RaceBaitR and Facebook.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more