I never imagined that I would get to this empowering place, especially not so soon in my life. In fact, it wasn’t until the last two or three years that I realized that such a place existed.

Where is this magical place?

It’s a place of self-love – a place where I have learned (and am still learning) to be at peace with my body, with my Self.

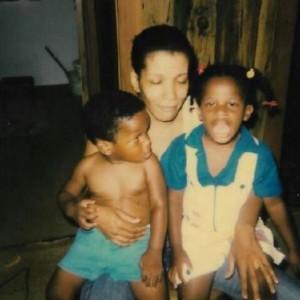

This was me at about four years old.

This was me at about four years old.

The little girl in that picture is an energetic, lovable, talented, beautifully brown-skinned pre-school aged child with something powerful to say.

I’ve always been that powerful, beautiful, talented, lovable person, but it’s not always how I have seen myself.

It’s still not how society sees me.

You see, I’m a 28-year-old, brown-skinned, fat, Black woman with unconventional looks (a wide nose, small eyes, short kinky-curly hair, and teeth with lots of gaps – they grew in that way, it’s hereditary).

And unfortunately, in our society, not only is this unacceptable, it’s considered worthy of ridicule, invisibility, and shaming.

And for years, I bought into that.

I coveted whiteness (light skin, but still brown enough that you could tell I was Black), I thought less of myself and my accomplishments because of my size, and I often imagined that I’d never find love because who – other than Belle – could love a beast?

I was bullied for my looks and size, on some level, for a significant portion of my life.

I’ve been called ugly by strangers on the street – in English and in Spanish. I’ve been told that my breasts aren’t “real” because it’s just “excess fat.”

And while I was well-liked by the overwhelming majority of my peers throughout my public school education, I was sometimes made fun of by a few people – behind my back, no less – for my size, looks, and nerdiness.

The fact that I managed to survive after being burdened with so many toxic messages for so many years is a complete miracle to me.

The fact that I’ve managed to shed many of them is even more amazing because there is a fundamental difference between surviving and thriving.

When you’re surviving, you’re still carrying the burden, although it doesn’t prevent you from moving. When you’re thriving, that burden has been lifted from you; you’re free to fly.

Three things have led me to where I am now: art, Health at Every Size, and sexuality. Without them, I can guarantee you that my thoughts about myself and my worth would have stayed stagnant.

The Art of Loving Blackness

In November 2013, I wrote about how seeing Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station changed my life.

The film follows the last 24 hours of Oscar Grant, a 22-year old Black man from the Oakland, California area who was shot and killed by a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) police officer on New Year’s Day, 2009.

I reluctantly developed a crush on the lead actor, Michael B. Jordan, and found myself having to deal with the reality of internalized racism, how pervasive it has been throughout my life, and how terribly it damaged my self-image.

Why was I so afraid to like him?

The question continued to gnaw at me.

After a lot of self-reflection and painful memories, I recognized the truth: I’d been so brainwashed into believing that whiteness (or as close to it as possible) was the only thing worth finding attractive that the thought of rebelling against what I’d learned was terrifying.

It was, in a large way, unknown territory to me.

While it continues to be a struggle, because I still live in a society that favors whiteness, I have grown so much in the 18 months since I saw that film.

That film – a film written and directed by a Black man, about a Black man whose life was snuffed out too early by a system that oppresses us – enveloped me in a warm, Black love.

Viewing that film initiated a journey towards self-love and self-reflection that I continued by surrounding myself with art that loves Blackness.

I began blasting songs like India.Arie’s “Brown Skin” and Jill Scott’s “Golden” like my life depended on it – because it does.

I spent more time in virtual Black spaces, such as Son of Baldwin’s Facebook page (follow him!).

And I affirmed myself in my worth by remembering my ancestors (biological and historical), our history, and – as dismal at it often seems as of late, our present – Black Lives Matter gives me life the way I imagine “Black Power” and “Black Is Beautiful” did for our forerunners.

I saturated my mind and my spirit in language, spaces, and people that valued who I was – from head to toe, inside and out – which helped me to value my physical and spiritual self in ways I never could before.

As a bisexual person and a woman, I have learned the value of safe spaces. They are a shield and a sword against a world that would rather I die than live – literally and/or figuratively.

Being Black, being fat, and having unconventional looks simply multiply that experience.

However, as a Black person, I was so indoctrinated into a world of whiteness that I didn’t know where to retreat; I didn’t know that I needed to retreat.

Sure, I had the Black church (for the record, a toxic place for a queer person like me), my family, and even the predominantly Black communities where I grew up.

But while there are many “Black spaces,” they are not always spaces that love Blackness. Black spaces that don’t love Blackness can be just as toxic as living in a white world.

“Loving blackness” is a term coined by Black feminist writer bell hooks. It is, simply, to love oneself not in spite of your Blackness, but because of it.

It looks like patronizing Black businesses, advocating for issues that affect our communities, and teaching our children the value of Blackness and all of our history.

It looks like valuing physical features that do not conform to the Eurocentric, Hollywood standard of beauty (without objectifying or exoticizing them) and making art that reflects these values in some way and tells our stories our way, like Fruitvale Station.

I did not get nearly enough of that in the Black spaces I grew up in, so I had no sword and shield to fend off the toxic messages that told me that my brown skin, wide nose, and full lips made me ugly.

I’m Fat, and I’m Okay With That

I’ve been Black all my life, and I’ve been fat for the overwhelming majority of it, too.

While the process of shedding oppressive messages about fat people started earlier than my journey to loving Blackness, it took longer for me to truly feel free from the idea that not only was I not good enough as a Black person, but I wasn’t good enough as a fat person either.

It was a double whammy that I lived with for pretty much my entire life, in addition to the effect of lookism – a triple threat of oppression based on appearance, if you will.

Unlike dismantling my internalized racism, the exact point at which I began to critique sizeist societal assumptions and come into my own as a fat woman is a lot less clear.

However, I began to scrutinize the oppressive messaging of “dieting,” and it was through this that I discovered Health at Every Size.

It has, in a few words, changed my life, just as Fruitvale Station did.

In the words of fat activist and all around awesome person Ragen Chastain:

HAES does not say that everyone can be healthy at any size – it says that body size and health are two different things and that people of all sizes get to choose how highly to prioritize their health and the path they want to travel to get there, and that the resources we need to support those choices should be available and accessible. With HAES the focus is on choosing behaviors [instead of focusing on weight], and allowing our bodies to settle at whatever weight they settle.

Like any movement (say, even feminism, for example), Health at Every Size has internal conflict and disagreements. It’s seen by some people as ableist (because of the term “health”) or creating a “good fatty” vs. “bad fatty” dynamic.

As someone with multiple disabilities, I think we all get to define “health” the way it best makes sense for our individual situations. There are many in the movement, such as myself, who assert that, ultimately, it’s about autonomy.

Does health matter to you? If so, what does that look like for your body? Day to day? Over time? If it doesn’t, what does matter to you?

It’s really an empowering idea when you think about it. It has certainly been empowering for me.

As someone who, due to growing up in a fatphobic and diet- and weight loss-obsessed culture, had a very dysfunctional relationship with food (and my body), HAES has been freeing in a way that is almost unimaginable.

I eat to sustain myself so that I can write these words, get to my babysitting gigs, and enjoy the company of others (or myself).

I move because the endorphins help with my depression, because I love rocking out to an eclectic set of music while I jog, and because it feels good.

I am no longer haunted by numbers on a scale (in fact, I seldom agree to be weighed in medical settings), and I no longer scare myself into not eating because of calories or the time of day.

I eat what makes me feel good, which might be scrambled eggs, buttered toast, and a bowl of strawberries in the morning; pizza in the afternoon; fish, brown rice, and mixed veggies for dinner; and rum raisin ice cream at midnight.

I am healthy as I’ve ever been, and that includes my mental health – I no longer feel trapped by a world that insists I shrink myself to fit in.

I am no longer a slave to the multi-billion dollar diet industry (which makes so much money because approximately 90% of people who lose weight gain it back, and then some – yay capitalism!).

While HAES, fat acceptance, and the body positivity movement are overwhelmingly white, I know that I can find solace in spaces for fat people of color.

Allowing Myself Some Healing – Sexual Healing, That Is

Finally, becoming more in tune with my sexuality has also opened up the door for an increase in body positivity for me.

While I know that being sexual isn’t necessarily for everyone, I’ve found that embracing my sexuality has allowed me to embrace my entire body in a way that I’ve never been able to before.

From masturbation to owning my sexual desires and choices, I’ve become more in tune with how awesome my body is for what it can do, how it makes me feel, and what it needs.

While before, when pleasuring myself, there were certain parts of me that I pretended didn’t exist as they are (my large belly, for example), masturbation became a way to recognize myself – the Self that was emerging because of my newfound love of Blackness and my size.

I challenged myself to touch my belly the same way I touched my breasts, like it was an important part of my sexual experience.

I challenged myself to touch my genitals in ways that I had been afraid to before because of an almost fear of the unknown.

I grabbed my ass the way I imagined I wanted someone to grab it for me, and suddenly, my body not only didn’t seem so bad, but instead it became pretty fucking awesome. (Plus it felt good, even if I didn’t always have an orgasm!)

I believe that my growth through loving Blackness and Health at Every Size was necessary for this last experience to happen, as coming to terms with my body as a whole allowed me the space to come to terms with (and love) my parts.

Of course, this is just my journey; many people come to this point at different intersections of their lives.

But, for me, it has been an amazing journey. I can look in the mirror and be happy with what I see most of the time.

I say “most of the time” because there are always battles, but I can proudly say that I’ve won the war.

I hope that this encourages you to fight for your Self, too. Take care of yourselves.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Denarii Monroe is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a poor, fat, bisexual African-American cisgender woman with multiple disabilities in her late 20s. Denarii is a syndicated writer for BlogHer.com and an aspiring screenwriter with a passion for youth and young adults. Check her out on Twitter @writersdelite.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more