Samsung just filed for a patent that would put a body fat sensor in their phones…

…and I am done.

Done with FitBit.

Done with Nike+.

Done with FitDay and FitSecret and CalorieCount.

I am done with the fact that Apple won’t let me delete the health app from my phone.

I am done. Because it’s annoyingly – and exhaustingly – apparent that we live in a world that worships at the altar of health.

Our authorities are not the great political leaders (they’re far too human and fallible, except for the ones who start the Paleo diet and lose weight, amirite?), but they who have the most defined abs. We celebrate health as a crowning achievement, with many in the health and fitness communities bragging about everything from their cholesterol numbers to their body fat percentage.

And how do they know about those cholesterol numbers or body fat percentage? Well, while health tracking used to be something your doctor did for you once or twice a year, we now have a million apps and devices to give us real-time progress logs and status updates on pretty much every metric related to our bodies.

And I call bullshit on it. I call bullshit on it all.

Why?

Because I believe that tracking your numbers, or self-quantification (as I’ll refer to this phenomenon for the purposes of this article), is a bigger problem than we realize.

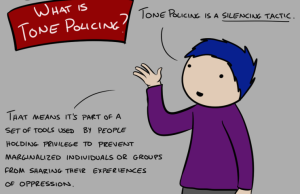

A problem disguised as the secret to health. A problem that’s causing us to consent to policing our own bodies – and giving others the right to police us – without understanding the consequences of what that consent means.

And I hope you understand that I’m not just sitting here with a tinfoil hat, worrying that the government is going to do something with the cholesterol numbers they’ve intercepted from my Wellness FX report or manipulate my genetics once they read my raw data from 23andMe.

I’m talking about the psychological toll of body policing and its connection to body shame, dieting, and disordered eating, and I think we need to take a look at three important ways that self-quantification may actually be doing us more harm than good.

1. Self-Quantification Reduces the Concept of ‘Health’ to Weight Loss

I know the trolls are going to come out of the woodwork as soon as they read the following words, but they have to be said: Weight loss is not the same thing as health.

Shall we say it together?

“Weight loss is not the same thing as health.”

That wasn’t so hard, was it?

Or maybe it was. And if you’re one of the millions of people contributing to our $61 billion weight-loss industry, then you’re (sadly) not alone.

We use self-quantification tools because we’re obsessed with weight loss and weight control, cleverly hidden beneath the seemingly innocuous term “health.” Because we don’t engage with calorie tracking apps or strap-on step counters because we actually have a benign curiosity about how many steps we’ve taken during the day.

We track because we want to prove that we’re making progress with our quest for immortality through “effortless” leanness. (Although I have some arguments about how “effortless” the process of logging all of your daily calories and tracking your blood sugar every three hours really is.)

But for many, the draconian rules that govern our culturally accepted ideas around body size actually create a situation in which our health actually declines when we lose weight.

For example:

Following a low-calorie, low-fat diet (aided by calorie counting apps and macronutrient-optimizing calculators) may result in weight loss, but that weight loss may also lead to disruptions in thyroid and sex hormones that lead to infertility, depression, and other unhealthy outcomes.

Overexercising to beat your own (or your friends’) best “scores” for calorie expenditure (steps walked, floors climbed, miles run, workouts “PR’ed”) can lead to exercise dependence, female athlete triad, and other unhealthy outcomes.

Supplementing to improve athletic performance, lose weight fast, or “biohack” your way to a “better” body size can throw off the balance of essential nutrients or even, in extreme cases, lead to death, which is most definitely an unhealthy outcome.

Obsessively trying to lose weight and restrict fat intake to lower blood cholesterol (and testing and tweaking and testing again) can actually be bad for your health, which, again, is an unhealthy outcome.

And none of this really touches on the mental health issues that can arise from the obsession and self-imposed oppression of self-quantification.

The problem is that we live in a society that is obsessed with body size and tries tirelessly to govern body size under the guise of health.

The Health at Every Size movement is constantly attacked by “well meaning” concern trolls who honestly believe that health can only be expressed in “optimal leanness” – and that anyone who hasn’t yet achieved that goal had better be constantly working toward it, and proving that they’re doing the work.

Even if you don’t think it’s a problem for you, and you are someone who uses these devices or apps, you are still complicit in this idea that health has a number or a goal weight, and that you must have proof that you’re working toward it.

To be clear, this is different from people who have to monitor their numbers for actual health reasons, like diabetics monitoring their blood sugar – because that kind of monitoring is literally a matter of life and death. Yet we act like the numbers spit back to us by Nike+ and our Bluetooth-enabled scales are just as critical.

But they’re not.

2. Self-Quantification Codifies Weight Loss as Morality

There is nothing new or interesting about self-quantification. We’ve been obsessed with the idea of controlling our weight and body size since—well—history. We’ve just never had so many ways to be myopically preoccupied until now.

And I’m not going to go into the whole sordid 2500+ years that we’ve been body shaming ourselves. You can go grab a copy of Louise Foxcroft’s Calories and Corsets and educate yourself. But suffice it to say that if Sophocles could have worn a FitBit, he would have.

Human beings are strange creatures. I’m going to generalize by saying we don’t like chaos.

The reason why we organize societies and give people labels and try to categorize the world so that no gray areas exist is because we need order. And order often comes from people agreeing to follow a certain code of acceptable behaviors.

And okay. Fair enough.

The problem, though, is that that code becomes morality, and those who don’t comply are a threat to society. So that we can maintain order, we must discipline those who break that code.

Now, the actual definition of “discipline” is “the practice of training people to obey rules or a code of behavior, using punishment to correct disobedience.”

But discipline is hard to scale, especially when the cultural code applies not just to your tribe, but across an entire political system. That’s where self-discipline comes in.

Codes of morality can be upheld when members of a society believe that it’s not just their duty to discipline others for breaking the code, but to discipline themselves.

In the Western, Judeo-Christian world, we have an unhealthily masochistic relationship to the concept of self-discipline. Flogging ourselves to prove our morality in the context of religio-political obedience is nothing new, but the human body is now a very visibly religio-political entity, and it’s increasingly easy to police due to the advent of self-quantification.

Here’s what I mean by this is: Body fat and ill health (while not the same thing) are viewed as threats to the health of our “civilized” society. Ask any thin, fitness-minded person about the obesity epidemic, and you’ll be treated to a rant about the burden on our health system and the disappearance of our tax dollars toward the treating of disease.

So, in an effort to be better biocitizens, we dutifully don our FitBits, hook up our Bluetooth-enabled scales, track our body fat percentages, and log our calories.

We monitor our bodies so that they either don’t get fat, or, if they are “too fat” to be considered morally and politically healthy, we monitor our progress to keep ourselves accountable, prove to others that we’re working toward becoming the allowed and allowable ideal, and punish ourselves for perceived discretions.

3. Self- Quantification Actually Reduces Our Quality of Life

How do you know if you need to be disciplined?

Well, you need a goal and a baseline – a weight, a certain cholesterol number, a calorie or macronutrient intake, a step count, a certain amount of REM sleep – in order to make that judgment.

We’ve got plenty of goals, in the form of generalizations and averages that were invented years ago and often faulty.

And what better way to establish a baseline and then find out if you’re progressing than self-quantification?

How many times have you looked at your wrist in the evening and, realizing you hadn’t reached your movement goal for the day, gone for a walk to hit your number even though you were tired? Or checked your ketones to discover with dismay that you must have “overdone” your carbs the day before and now “must” double down on your efforts to get into ketosis (and lose weight, of course).

Because you don’t just quantify because you’re curious; you quantify because you want to change a behavior, whether it’s eating too much, eating too poorly, not moving enough, or not getting the “right” kind of movement.

And you don’t just want to track whether or not you enact that behavior – you want to correct that behavior. And how do we often correct behaviors? Through punishment.

Trust me, I don’t know too many people who look at their calorie counters on a “bad food day” (note: there’s no such thing; I’m just using the language that others might use around their eating behaviors) and say, “Hm, how interesting. I’ll choose to eat differently tomorrow.”

Even if you’re not a disordered eater, when you have a “bad food day,” you feel like you have to “repent.” So you reduce your calories or do a juice cleanse or work out for an extra hour. And you make sure to log it all to prove to yourself that you’ve truly repented.

So I’m going to say something controversial here, but I don’t care: I believe that self-quantification, which is meant to contribute to and increase your health, is actually taking away from your quality of life.

The faulty morality of a prescribed body size is distracting us from the fact that we’re being encouraged and trained to punish ourselves. And having our tools so readily available makes it an easy distraction to which to succumb.

And it’s getting worse: More than just being able to track our runs or write down our meals, the makers of our tools have pretty much “gamified” everything from walking to the mailbox to eating “clean” – so we’re constantly engaged in the pursuit of reaching goals, breaking records, and publicly announcing our “wins” while “beating” our friends and family (and strangers on the social media leaderboard).

I’ve seen Internet memes with phrases like “I forgot to post on Facebook I was going to the gym. Now this whole workout was a waste of time.” And the sad part is that for many of the 223 million people using their health tracking devices – many non-eating disordered or exercise-addicted people – that sentiment isn’t a joke.

In a recent survey of FitBit users, 79% of women actually said that they felt pressure to hit their daily targets, while nearly 60% felt like their daily routines were controlled by their FitBit. 43% felt like they’d wasted their efforts if they had forgotten to wear their FitBit while doing an activity.

Feeling controlled by your device and crestfallen when it’s not actively recording your every move shouldn’t be considered a normal state of being, and yet large percentages of people who don’t have eating disorders or exercise addictions walk around tied to their devices and desperate to make their numbers.

The same goes for calorie counters. While documenting your calories for a week or two may help you gather a baseline idea of your current diet and food intake, over the long term, it can contribute to obsessive behavior and devalue the quality and enjoyment of your meals.

Moreover, the self-quantification movement keeps us aware of our bodies in a rather negative light. A recent international study actually found that telling overweight subjects that they were overweight made them more prone to overeating and weight gain than if they hadn’t raised the subject in the first place.

That’s kind of a big deal – because it sheds a lot of a light on what happens when we start to fixate and obsess about fixing ourselves: We become so attuned to the need for self-punishment that we feel like failures when we “mess up” or don’t reach some unattainable goal in the first place or fast enough.

Now, I’m not going to get into the politics of why fat is not actually a disease, because that’s a whole article (or masters thesis or twelve) in itself, but for the sake of getting through this argument, let’s just go with the idea that we don’t, on the whole, need to be self-disciplining ourselves around the size, weight, and shape of our bodies.

***

Most of us – if we just trusted ourselves a little more, dieted a little less, and added some form of joyous movement into our lives – would be able to live relatively healthily without too much drama, despite the fact that our bodies might not look the way we think they’re supposed to.

So each time you start using your tracking device or app of choice, think about what it is you’re measuring.

Ask yourself why you’re measuring, and what you intend to do with the numbers.

And even if you think you’re just playing a game, you have a duty to examine your behaviors and how they’re actually contributing to or removing from your quality of life.

Because perfect health and a “perfect body” is not a moral imperative – and if it’s ruining your quality of life or the quality of life for those around you, then it’s not actually healthy at all.

And that’s a fact you can count on.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kaila Prins is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a health coach who works with women who are ready to stop “recovering” from disordered eating and start “discovering” their true identities. Kaila’s health coaching services, as well as her blog, can be found at In My Skinny Genes, and she hosts a weekly podcast called Finding Our Hunger. She also counts characters and not calories on Twitter @performingwoman.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more