If you’d asked me this question a year ago, I would’ve had a completely different answer – which means that this video is going to be a doozy.

Self-objectification. What a weighty topic. But before we can get into whether or not it’s possible for a woman to objectify herself, first we need to be on the same page about what objectification is.

In the social sciences, the word objectification is used to describe the act of treating a person as an object, thing, or possession. It’s harmful because it involves, among other degrading qualities, a denial of autonomy and subjectivity.

Objectification turns a person from a living, breathing, feeling being into—well—about as living, breathing, and feeling as a crumpled up piece of paper.

Now, you can do whatever the hell you want to a crumpled up piece of paper because it doesn’t have any rights, needs, or emotions. Right?

You can kick it, throw it into the trash, hang it up on your wall like it’s art, or whatever else will serve a need for you. And when we look at a person as an object to whom we “can do whatever the hell we want,” that’s a problem.

In the case of feminism, often, when we talk about objectification, we’re speaking about the ways in which women are seen as objects of the male gaze.

The term male gaze was coined by Laura Mulvey, a film critic, in 1975. Specifically, Mulvey was talking about the ways in which movies and other media are centered around the assumption of a male viewer. That is, women are depicted through the lenses of men and in relation to the experiences of men.

In media, we see this happen in three main ways: 1) the person behind the camera or in charge of the media is a man (on screen text: 97% of clout positions in media are held by men); 2) the audience is assumed to be made up of men, and 3) the women characters are represented as furthering the stories of men. All of which takes womanhood and guts it: Women are given no voices, no stories, no humanity – and therefore, no respect.

The male gaze objectifies women because it reduces us to our bodies and appearances, and it silences us. For example, in advertisements, sometimes you literally see women represented as objects – like a chair or a rug. Or sometimes you see objects represented as women – like bottles or cars. The idea is: You could switch out a real live, breathing, feeling woman with an object, and it would make no real difference.

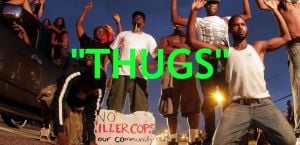

Objectification in and of itself is dehumanizing. Dehumanizing means, after all, to deprive of human qualities. But objectification is also a symptom of a larger patriarchal rape culture – patriarchy meaning a society that devalues women and femininity, and rape culture meaning a society that excuses and normalizes sexual violence.

Take masturbation, for example. You can masturbate with any inanimate object that you want – although, uh, some are safer than others – but because inanimate objects don’t have rights, needs, or feelings. But with a person, you have to take their rights, needs, and feelings into consideration before being sexual with or toward them. When you don’t, you’re committing an act of sexual harassment or violence. So when we live in a world where women are routinely objectified, we also live in a world where violence committed against them is frequent – and isn’t taken seriously.

And I think that’s why people automatically bristle at the notion of self-objectification. Because it comes off as saying that it’s possible for women to invite objectification – and therefore, potentially, violence – onto themselves. And that’s fucked up. No one can make you objectify them. As an acquaintance of mine who used to work at Playboy once put it: “Objectification is something the audience brings to the party.” It’s something that someone (or society) does to you, not something you create yourself. And no one can ever, ever be blamed for other people objectifying them.

But what happens when the audience, itself, is you? Here’s where things get a little sticky.

Objectification theory is a framework that explores how womanhood is experienced in a social context that sexually objectifies women and associates their worth with their appearance and sexuality. And according to objectification theory, objectification can happen in two ways: externally or internally.

Some of you may be familiar with the term internalized misogyny. When feminists talk about internalized misogyny, what we’re talking about is how society’s hatred of women and femininity becomes so engrained in us that it’s to the point that we act it out ourselves. If you’ve ever heard a woman call another woman a slut, for example, that’s internalized misogyny. When you consider the ways in which many women hate their bodies, that’s another example of internalized misogyny. It’s when we take the sexist messages all around us and we start to believe them, therefore applying sexism to ourselves and each other.

Internal objectification would, basically, be, then, when we, ourselves, reduce our bodies to objects and stop taking into consideration that we have rights, needs, and feelings. So, is that possible? Sure. I guess it’s within the realm of possibility to internalize misogyny, the male gaze, and objectification to the point that we, ourselves, believe ourselves to be worthless, without autonomy, and without subjectivity.

But it sure as hell isn’t common.

Generally, when we talk about women self-objectifying themselves, we’re actually referring to women who are celebrating their whole selves – bodies included. Acknowledging, appreciating, and glorifying the fact that you have a body is not objectification. Acknowledging, appreciating, and glorifying your appearance is not objectification. And acknowledging, appreciating, and glorifying that you’re a sexual being isn’t objectification either. That’s just noting the ways in which you are whole. Which is the exact opposite of objectification.

So, is it possible for women to self-objectify themselves? Meh, maybe. But I think we should be a lot more worried about the ways that society routinely devalues women and femininity, including through objectification. Because that’s the real problem – not that babe on your Instagram feed in her skivvies.

Until next time… (blows kiss)

This video was made in collaboration with Everyday Feminism, a website dedicated to helping you break down and stand up to everyday oppression.

***

References

Fredrickson, B.L. & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402-1997.tb00108.x

Langton, R. (2009). Sexual solipsism: Philosophical essays on pornography and objectification. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6-18. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

Nussbaum, M. (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24(4), 249–291. doi:10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x

Leavy, P. & Trier-Bieniek, A. (2014). Introduction to gender & pop culture. In P. Leavy & A. Trier-Bieniek (Eds.), Gender & pop culture: A text-reader (1-26). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.