Source: eHarmony

Have you ever criticized a woman for the way she looks? wished you could look like the models that you see in fashion magazines? gone on a diet? shaved off any of your body hair?

If you’re a woman (or even if you’re not!), you’ve probably done at least one — if not all — of these things at some point in your life.

But have you ever done any of these things after finding feminism? even when you knew that you were practicing sexism or giving in to the pressures of our patriarchal society?

My guess is that your answer is still yes.

How do I know? Because I’ve done all of these things after proclaiming myself to be a feminist.

We all can be complicit in our own oppression. It’s not always other people or other genders that are responsible for sexism. Sometimes, it’s actually you.

Hear me out.

How Internalized Misogyny Happens

Internalized misogyny is the “involuntary internalization by women of the sexist messages that are present in their societies and culture.”

Basically, that means that we hold misogynistic ideas ourselves, even though we are women. It’s involuntary because the sexism that is present in our culture is taught to us through socialization (the process of learning culture through social interaction), a process we don’t have much say in.

We aren’t born sexist.

It’s not like you pop out of the womb already thinking that women are inferior beings. It’s through observing, learning, and understanding society that you come to hold common attitudes and beliefs, including misogynistic ones.

Socialization is part of personality formation, meaning that it shapes the ways in which you think about yourself and others, relate to the world around you, form attitudes, and behave. That’s why people of certain identities and people from the same culture will often exuberate similar personality traits and engage in similar behaviors.

This is because of how the socialization process works – because its purpose is to shape one’s personality to fit that of the others in their identity group and culture.

The larger goal of socialization is uniformity.

For example, think about the ways in which men and women sit differently in Western society. Just take a look around you and observe on a train, in a doctor’s office, or even a restaurant, if you can’t think of any differences.

You’ll probably notice that men tend to sit widely, with their legs open, and women tend to sit with their legs crossed or together.

Why is this? Obviously women aren’t born with the instinct to sit with their legs together, nor are men born with the instinct to sit with their legs apart. It’s socialization.

The ways in which we sit are gendered (like pretty much everything else that we do) and is something we learn through observation, or perhaps even direct education. Have you ever had someone tell you to “sit like a lady?” That’s socialization.

When you hear your mom talk about how fat she is or your uncle make a sexist joke; when you see diet pill commercials on television or listen to your babysitter call someone a slut – these instances don’t just go over your head, as many people like to believe. In reality, you’re taking in these messages.

And although one of these moments might not seem like it can make much of an impact, thousands of them will — and do.

These messages will not only become a part of how you think and perceive the world, but how you think and perceive yourself.

That is, in short, how internalized misogyny becomes an involuntary part of your thinking.

Until we liberate our society from the sickness of sexism, internalized misogyny isn’t going anywhere.

Understanding Choice Feminism

Now that the concept of internalized misogyny has been wired into your brain, next comes the ways in which this ties into feminism.

There’s always a lot of talk about how feminism means choice. The argument is that even if a woman is participating in what is deemed to be a patriarchal or oppressive behavior, they are making their own choice — therefore, that choice is a feminist act.

Let’s say that you’re getting married and you decide to take the last name of your spouse-to-be. If you were to ask people if this choice is “feminist,“ you would probably hear someone say something like, “Well, you’re choosing to do it by your own free will, so that’s a feminist thing to do.”

Now, a woman taking the last name of her husband is based in the tradition of women being the property of men. Since she became literally an extension of him, she had the same last name.

But those days are over, right? Changing one’s last name is no longer mandatory! It’s optional, so you can choose to do it.

Not so fast.

Here’s something else to consider: Are things like this really a choice?

Or are they, in fact, often a consequence of oppression?

Sure, I can choose to not shave my legs. There is no law requiring me to do so, and I am able to make the decision not to without facing legal consequences for it.

But I will face social consequences.

I’ll probably be stared at. I might receive disapproving glances from strangers. I might have potential dating prospects choose not to approach me. People may make rude comments. I could be turned down for jobs or friendships. I might even be harassed.

So shaving my legs is not entirely something I choose to do by my own accord or because making micro cuts into my leg sounds like my idea of a fun Thursday night.

I shave my legs because of body policing.

I shave because not doing so means I’ll be shunned and doing so means I can go out into the world and increase the likelihood that I will be accepted by society.

But it’s not just the misogyny of society at work in this decision. It’s also my own internalized misogyny.

I shave my legs because I like how they look and feel when they are shaved. When I look at the hair on my legs, it makes me feel gross and dirty. I feel more feminine when my legs are hairless.

This is an example of my own internalized misogyny at work.

The same applies for changing my last name if I get married; women are no longer required to do this. It’s just an option.

But not changing my last name if I get married also has social consequences. I would probably be bombarded with questions from friends and relatives as to why I wouldn’t want to share a last name with my spouse, I would likely be viewed as being a bad partner for not doing so, and would have to deal with every side-eye I receive when I don’t respond to “Mrs. _____.”

But I would also probably view myself as not being a good wife, too. There’s that internalized misogyny, again!

So no, simply making a choice is not a feminist act. But more importantly, in reality, these weren’t even real, honest choices to begin with.

Beyond Logic

This is why being a feminist doesn’t mean that we magically completely free ourselves from the bondage of the patriarchy.

Even when we understand why we do things that are rooted in sexism, or are angry with ourselves for doing these things to begin with, our internalized misogyny and our culture’s misogyny force us back into the very ideas we reject.

Women don’t actually have a lot of choices that don’t come with social consequences.

This is why the argument of choice feminism crumbles: because it often doesn’t actually involve choices.

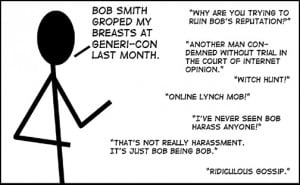

Feminism Doesn’t Do Away With Anti-Feminism

Since not all choices are feminist, and not all “choices” are actually choices, being a feminist doesn’t stop you from doing things that are anti-feminist.

There’s this idea that if you’re a feminist, suddenly everything you do becomes a marker of feminism.

And that’s simply not true.

Feminism isn’t a magic potion that causes you to not do anything that goes against it. The fact is, people are complex and multi-faceted, and feminism doesn’t constitute someone’s entire identity or sense of self. Being a feminist doesn’t mean that you’re “on” or perfect 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Feminists do anti-feminists things all the time.

But the point is: That’s okay.

It’s okay not to be “perfect” or live up to society’s (or the movement’s, for that matter) idea of what a feminist is supposed to be like.

It doesn’t make you a bad person – or a bad feminist.

Why? Because we live in an anti-feminist world, for one, that rarely gives us agency to live feminist-ly. As was earlier discussed, we don’t really have choices about a lot of things that society might try to tell us are choices.

Also, because feminism is out to destroy this idea that women need to be perfect or live up to an ideal womanhood.

Because forcing women to be a specific kind of woman is exactly why feminism began in the first place.

So yes, you’re probably going to do anti-feminist things. But that doesn’t have anything to do with you’re worth as a person, or a feminist.

***

The society we live in doesn’t give us many alternatives.

So the next time that you ask yourself if what you’re doing is really feminist, remind yourself that even if it’s not, it’s okay.

You don’t have to channel bell hooks all the time to be a “good” feminist or drive yourself mad trying to make sure you’re not doing anything to support the patriarchy.

The fact is that we live in an anti-feminist world, so naturally, our day-to-day lives aren’t filled with options that are always in-line with our ideals. “Giving in” does not make you a bad person.

Society is who’s at fault, not you.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Want to discuss this further? Visit our online forum and start a post!

Erin McKelle is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s an e-activist, video blogger, student, and non-profit advocate who has launched several projects, including Fearless Feminism and Consent is Sexy. In her spare time, Erin enjoys reading, writing bad poetry, drawing, politics and reality TV. You can visit her site here find her blogging at Fearless Feminism, Facts About Feminism, and Period Positive. Follow her on Twitter @ErinMckelle and read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more