Three people in the background appear to be whispering about another person in the foreground.

(This article has been translated here in Spanish.)

What does liberation mean to you?

When I was younger, I was well aware of the fact that some people were treated differently based on how they looked and acted. Those who were treated the poorest were often those who were the poorest, and those people generally looked like me.

Black people, especially Black women and gender non-conforming people, could not go anywhere publicly without at least the threat of some sort of violence against them. Many non-Black people of color lived through similar violent realities.

Meanwhile, white people, especially white cisgender men, did not have to worry about being followed around in stores, being constantly mistaken for criminals and treated as one as well, or never being given the benefit of the doubt, all things I had learned to become so accustomed to.

I envied this. I thought freedom was to be able to move through the world like them. I thought being free was to walk without the cares and burdens I was forced to carry.

Liberation became synonymous with whiteness.

This thinking was exemplified in ways that were obvious examples of internalized anti-Blackness, and as well as many that were less obvious.

It was in disdainful rants against those whom I considered “ghetto” (as a kid from the ghetto myself, no less). And in feeling as though the only way for me to succeed was by getting as far away from Cleveland as possible, even when I didn’t know or admit that it was Blackness I was running from.

As any thorough analysis of respectability politics will expose, Black people can never fully escape our Blackness. With the aim of “respectability,” sometimes we think we can earn humane treatment by dressing, acting, or talking a certain way.

But we are treated inhumanely in suits and in hoodies, with degree in hand or while holding forties instead.

I came to better understand that respectability wasn’t a solution for me not too long after arriving in NYC, but it took a little longer to comprehend the full implications of this truth.

My desire to find freedom in the ways white people are “free” was not only impossible, but harmful to myself and other Black people.

Do you desire this kind of freedom?

White people never being seen as suspicious, despite warranting suspicion, means white people getting away with violence. To always be given the benefit of the doubt means always giving the detriment of it to someone else.

Within whiteness, being “free” means taking up space with no regard for whom you are taking it from.

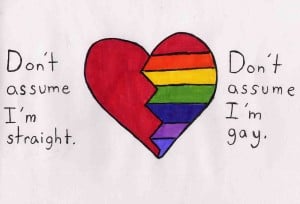

It later became clear to me that the conflation of freedom with “how white straight cis men move about the world” shows up in our activism all the time. In obvious ways – like prioritizing gay marriage over queer youth homeless – but also in less clear ways, like fighting for gun control bills with racist implications.

This kind of ideal of freedom is always ultimately anti-Black, and Black people always end up losing as others obtain it.

Queer youth homelessness is disproportionately a Black problem. Gun control has historically been a weapon used against Black communities, and there is no reason to assume it would be anything different today.

Usually, these ultimately anti-Black fights disguise themselves as great intersectional activist causes, and it can be hard to distinguish between work that seems intersectional and that which ultimately harms Black folks.

That means anti-Blackness might be showing up in some of the ways you think you’re practicing intersectionality.

But you can recognize this happening and make a change by looking out for a few red flags I’ve come to discover over the years:

1. You Emphasize Similarities to Gloss Over Differences

“At the end of the day, we are all the same!”

You’ve probably heard or said some iteration of this in your activism.

It feels like a great way to build forces is to find connection with other people who might not immediately recognize their alignment with you. This is part of the reason why we attach ourselves to umbrella terms like LGBTQIIA+ and talk so much about “solidarity.”

While finding commonalities is important, it does not negate the truth that people actually are different. And many of those differences are by design.

“Rather than emerging from a scientific perspective, the notion, ‘race,’ is informed by historical, social, cultural, and political values,” writes Teresa J. Guess in The Social Construction of Whiteness: Racism by Intent, Racism by Consequence, “thus… the concept ‘race’ is based on socially constructed, but socially, and certainly scientifically, outmoded beliefs about the inherent superiority and inferiority of groups based on racial distinctions.”

Blackness especially is always different from those in power under white supremacy.

This is why the same thing that can be celebrated when a white person or even another people of color does it (i.e. rap) can be demonized when Black people do it.

When we ignore for the sake of “community” that people move through the world differently, what we are also doing is ignoring the needs of those who are most different for the sake of those who are least.

This benefits people of color who are closest to white concepts of humanity and does nothing for everyone else. Under whiteness, “everyone else” is usually Black, poor and working class women, trans, non-binary, disabled, and queer people.

Differences are only the problem when homogeneity is the goal. Think about it: Why should everyone have to be the same to be treated with dignity?

It’s how we treat those who are different from those with power and that is the concern of a just society.

2. You Want ‘Everyone to Be Treated Equally’

The concept of equality is enticing.

But, as mentioned earlier, the “equality” that we desire is usually a stand in for “how white people are treated.” Being treated that way always comes at the detriment of others, especially Black folks.

Scholars have explored in depth how white people gain access through human subjectivity only through the creation of an “other” racial designation that lacks humanity. White people are treated the way they are because they are positioned in contrast with those treated the way they are not, or inhumanely.

So, when we seek “equal treatment” or “to be treated like human beings,” while understanding freedom and humanity through the lens of whiteness, we are often seeking only to be treated better than those who represent Blackness the most.

This was demonstrated in how the problems associated with HIV/AIDS were addressed. Unless the face of HIV was white, it was not a problem for the entire queer community.

Even now, when HIV rates remain at epidemic proportions in Black communities, with 50% of gay Black men expected to contract the virus in their lifetime, the issue is heavily being addressed in a way that requires access that the most vulnerable will not have.

Can we really say we’re creating a world that’s better for everyone if our vision of “equality” leaves the most vulnerable people behind?

“Equality” does not distribute resources where they are needed most, and where it is needed most is often in Black communities.

Focusing instead on true justice and liberation means you’re not simply treating everyone the same. Instead, you recognize that different people have different needs, and you can give marginalized people the kind of support that’s best for them.

3. Your Approach Focuses On Eliciting Empathy

So much of our work is done for the implicit or stated purpose of getting others to witness the humanity of marginalized people.

We remember how feeling the pain of someone else through images forced us to act and thus position our work to be that same kind of motivating factor to others.

But the thing about empathy is that it requires one to be able to connect with the person they are seeing in the first place.

When it comes to getting others to “feel our pain,” this generally means that such pain has to be shown in a particularly grotesque and offensive manner, leading to looped massacres – often of dead Black people – over and over again.

You might think you’re being a good ally by sharing tragic YouTube videos for all your friends to see.

But not only is this triggering for those who have to re-experience their own traumas, it is based on the fallacy that there is the same human connection that can be elicited between everyone.

With whiteness requiring some of us to be seen as non-human, this only works for the rest who might be closest to humanity – or at least works best.

In other words, this kind of empathy will never be enough – and while you get to feel better because you think you’ve done a good thing, Black people still aren’t fully recognized for who we are.

Empathy will always benefit those who are in the position to best be empathized with over those who need care the most.

4. It Upsets You When People Don’t Celebrate ‘Progress’ or Incremental Change

Because incremental change always and only benefits those closest to the people in power in the first place, those farthest away will likely never benefit.

Under white supremacy, this means those who most fully represent Blackness (the poor, queer, femme, disabled and women among the community) have nothing to celebrate.

For example, it might be okay to cheer victories like gay marriage, but if you don’t recognize that some of us will never have access to the benefits of the marriage institution despite the leveling of this legal barrier, it’s clear you aren’t focused on the people who are still left out.

Sure, this perspective puts a damper on the celebration. But it also keeps you from getting complacent and settling for incremental changes that don’t actually address the root of the problem.

If it upsets you when the people who are still struggling point out this reality, it’s clear that you don’t want to focus on them.

5. You’re More Concerned About Marginalized People Gaining ‘Rights’ Than People Who Aren’t Losing Power

Because incremental progress should never be the goal (even if it is celebrated), we have to make sure that we are always focused on dismantling the power system in general.

In order for this to happen, we can’t just stop at “gaining rights” – we have to ensure that there are no barriers to them in the first place.

These barriers are created by implementing systems such in which humanity is only for some and not for others – systems like white supremacy.

If your activism prioritizes (some) people gaining rights over destroying the system, or doesn’t consider that part at all, it will never be activism that benefits the Blackest and poorest of us.

Giving up and taking away that power away is the much more difficult and daunting task, as you’ll find most necessary ones to be.

I shouldn’t have to try to prove I can be “just like a white man,” or beg for your empathy, or celebrate small victories that harm my community more than they help, just to get your support and solidarity.

***

It’s going to take some deep work to actually address issues of injustice in a way that lifts up the most vulnerable among us – but we shouldn’t have to settle for anything less.

Wouldn’t you prefer a world that completely dismantles harmful systems to one that just helps the most privileged among us navigate them safely?

It’s time to look beyond the limited concept of “freedom” that’s been presented to you. Black people have been advocating for more for years, so other options are available.

Freedom has to be a concept that includes not just the margins, but the margins of the margins. Anything less will always ultimately find itself to be anti-Black.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Hari Ziyad is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a Brooklyn-based storyteller. They are the Editor in Chief of RaceBaitR, a space dedicated to imagining and working toward a world outside of the white supremacist cisheteropatriarchal capitalistic gaze, and their work has been featured on Gawker, The Guardian, Out, Ebony, Mic, Colorlines, Paste Magazine, Black Girl Dangerous, Young Colored and Angry, The Feminist Wire, and The Each Other Project. They are also an assistant editor for Vinyl Poetry & Prose. You can find them (mostly) ignoring racists on Twitter @RaceBaitR and Facebook.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more