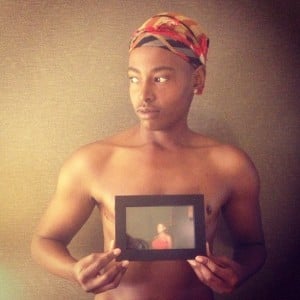

Credit: Adreinne Waheed

“Straighten out your wrist, Brotha!” When my boxing coach yelled these words, I knew his call was about more than perfecting my jab.

I have experienced the demands of Black masculinity and the responses to my failure to perform properly are not all that different from the experiences of failed masculinity that I felt within Black lesbian communities.

But it is true, I am now a young Black American Male. People usually assume that I am somewhere between the age of 15 and 20. I’m 28.

The world is unkind to Black bois. The world is unkind to Black girls. But the way our gendered bodies are policed is different. Black bois are assumed thugs, thieves, rapists, and overly aggressive.

I knew this already, but I feel it more now like when I got kicked out of a Hollywood store because the owner assumed I was there to steal something.

He didn’t just make that assumption. This white man came over and hovered over me yelling for me to get out and to never return because “he knew my kind.”

I spoke calmly, but he kept yelling. I couldn’t help but think, “this man can’t see or hear me.”

He could only see what he believed to be true about young black bois, and it didn’t matter who I was, who I had been, or who I might become. My future and past were predetermined in his mind.

I was the dangerous body that needed to be policed.

And Black women have it too. Bearing the brunt of pathology, the Black woman has been told that she is the reason why Black people suffer. Because she has been too strong and emasculating. Because she is crazy and angry.

She needs to be put in her place by Black men and those outside her racialized community.

When my boxing coach told me to straighten out my wrist, it came after lots of criticism around my push-up form, my strength (or weakness). The way my body moved was sub-par especially in comparison to this ripped Black man.

I have gone from being a big, strong looking Black woman to occupying the body of a young, lanky Black man. The more my body masculinizes, the more I feel my femininity stands out as contradictory to those who invest in normative types of masculinity.

So What is Masculinity? How Did I Come To Learn How To Wear It?

When I was in high school, I learned there was a code to same gender loving life. You were either masculine or femme, a stud or her girlfriend.

I was told that my look was confusing. People couldn’t tell what I was. Someone told me that I was sporty “femme.” I didn’t know what that meant but I was happy that I had a name to call myself, a place to belong.

The first woman I went on a date with was masculine presenting, a stud. She had a way of making me feel her masculinity as a direct opposite to my femininity.

I didn’t like the room I was given to move or to not move.

I know that this interaction was circumscribed by chivalry. She opened my door and closed it. She paid for dinner. Something about this interaction made me feel trapped.

I decided that I would be nobody’s femme and therefore I must be like her, a masculine woman, a stud.

I wanted to be in control.

I took the summer to learn my gendered role. I became a stud. And it worked because I was able to get the attention of the femmes that I was attracted to.

In those early teenage years, I mostly learned from other studs how to be. I remember the first time I learned about stud misogyny. I was 18 or 19 at the time and I was at a house party in the Bay.

There were many beautiful Black women in the space. There were studs and femmes. The host was a stud who wore cornrows, baggy jeans, and perhaps a polo or a jersey. She was good looking, but somehow I knew that was something I wasn’t supposed to articulate aloud.

I remember looking at her and examining the family photos that had been on display in her house.

The girl in the picture was different. She was femme. She smiled.

I wonder if the girl in the picture felt like she needed more room. I wonder if the stud she had become gave her more room.

I wonder how that room, that liberation that she felt came from dominating feminine women or perhaps the feminine that might have been a part of her.

I remember walking in on a conversation between two studs. One told the story of how her girlfriend broke her chain and how upset she was.

The other stud chimed in, “If that had been my girl, I would have slapped her.”

Everyone laughed, but I was afraid.

That’s probably one of the earliest moments that I felt uneasy about being a stud and the kind of masculinity we were creating and inheriting.

Another lesson in studly masculinity came for me when I was in college. I had fallen for an older femme woman.

We’d spend time walking and holding hands in the New England chill. She taught me how to be a good stud.

“You should always walk on this side of the street, so that I feel protected.”

“You should always open the door for the lady.”

I was getting schooled in old-fashioned chivalry and I was good at it. I was in love with it. The giving, the idea that I could somehow protect.

But it wasn’t simply that I could protect. There was an insistence that I MUST.

Anything else meant failure.

What if I was afraid? What if I needed to feel/be protected? Well, that was the sacrifice of normative masculinity.

After I had top-surgery, I needed help with my carry-on bags when flying. I wasn’t able to raise my arms above my head. No one could see that I needed help. I didn’t have any visible wounds, so I had to ask.

I asked a white stewardess for help and she glared at me. She was annoyed and she didn’t want to help me. I explained to her that I had just had surgery and still annoyed, she told me that next time I would need to check my bag if I couldn’t do it myself.

I was a young, seemingly able-bodied Black man. I wasn’t elderly.

Why did I need help?

How can we expect to create healthy men and bois, if they live in a society where asking for help is met with punishment and enforced shame?

Is there room for vulnerability in masculinity? We must make room.

Who I Am Today

I walk in the world today as an effeminate Black transman. Queer, indeed!

I never want to straighten out my wrist. I want it to flare, I want it to paint flame across canvass because I am unafraid of femininity.

It is the place from which I garner my strength.

The term Masculine of Center has been one that I have clung to for sometime now. Masculine of center (MOC) coined by B. Cole of the Brown Boi Project, recognizes the breadth and depth of identity for lesbian/queer/womyn who tilt toward the masculine side of the gender scale and includes a wide range of identities such as butch, stud, aggressive/AG, dom, macha, tomboi, trans-masculine etc.

When I discovered it, I thought, “Finally, a term that can hold me!”

But as I sit here today and write, my center feels feminine. Is there room for that? We must make it.

I have always carried with me both masculine and feminine energies, but I have often been forced to choose one over the other depending upon the space around me.

I have been on hormones since July 2011. I had top surgery in May 2012. It is 2013 and while some things have clearly changed physically and emotionally, some things have stayed the same.

I still bleed every month. For many this may seem to be a contradiction to my masculinity or maleness, but I cherish the moments.

I am thankful that my body carries both masculinity and femininity at its core, because at the end of the day, what we should all be striving towards is balance.

We need to build relationships between men and women that allow space for both parties to grow.

We need to build relationships between men and men, women and women, that allow space for both parties to move freely.

The gender binary affects us all in detrimental ways. And while masculinity may seem to offer more room, it also has its limitations.

And femininity, if only understood as masculinity’s property, is detrimental to women and other people who identify as femme.

Hi, my name is Kai M. Green. I am a Black Transman. I am a Black feminist and my center is just as feminine as it is Black.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Kai M. Green is a filmmaker and a spoken word poet who examines through film and poetry questions of gendered and racialized violence and a PhD candidate in the department of American Studies and Ethnicity at The University of Southern California. Learn more about him on Youtube and his blogs, Kai’s (Bi)Weekly Jams and In The Darkness: My Dissertation Journey, book him for speaking engagements here, and follow him on Twitter @Kai_MG.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more