Source: Wellness Everyday

As I’ve watched the whole Dolphins Bullying fiasco unfold, I can’t help but sit in shocked amazement at how many of the Dolphins players and management are in defense of Richie Incognito’s racist and homophobic bullying of Jonathan Martin.

I can’t help but wonder how many voices are silent.

How many team members or coaches were disgusted by Incognito’s behavior but didn’t speak out for fear of drawing the ire on themselves or for seeming to go against the grain?

How many people in the organization want to see a more positive culture in the locker room?

How many of them would have stood up if they simply had the tools before it got to the point of Martin walking away from a lucrative contract because of bullying?

It’s Time for Tools

Half of the battle in addressing bullying is getting people to understand the particular nature of modern bullying, particularly in its connection to power, oppression, and identity.

Bullying has changed profoundly in the Internet era. Yet it has simultaneously stayed the same in how it disproportionately targets the most vulnerable identities in our communities.

Prevention starts with this understanding.

But understanding the problem does not necessarily inspire action.

The problem itself can seem too overwhelming, so profoundly entrenched, that we can get stuck in analysis and never act.

What’s encouraging, though, is that when committed stakeholders from every corner of a community commit themselves to acting to build a more inclusive environment, it is, in fact, possible to prevent bullying behavior.

But we have to empower our communities with tools!

So What Constitutes Bullying?

First, in order to offer people tools, we have to be clear about what we mean when we say “bullying.”

Too often, any mean behavior is called “bullying.” Sure, we definitely need to address hurtful language that someone uses, but is it really bullying?

The definition we use for bullying at CivilSchools breaks it down this way: Bullying means targeting another person for regular, sustained violence, harassment, or neglect because of a particular aspect of that person’s identity.

There are three key parts to this definition.

The first relates to the behavior being regular and sustained. If someone is made fun of once, that is a bad thing, but it isn’t bullying behavior. Bullying must target someone over time.

The second describes the behavior: violence, harassment, or neglect. Not all bullying is characterized by physical assault or verbal harassment. Sometimes bullying involves a coordinated isolation of another person to make them feel alone.

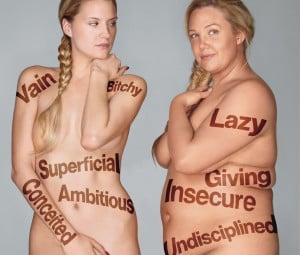

Lastly, bullying usually isn’t random. It targets another person for a particular aspect of their identity.

Sometimes people are targeted for more surface-level aspects of identity like interests (music or sports, for example). Other times, bullying targets more deeply-held aspects of our identities like our race, gender identity, body image, physical or cognitive ability, or sexual orientation.

Regardless, it’s important to describe bullying as identity-based because it helps us target our interventions at the root of the bullying behavior.

Here are five ways to start putting an end to bullying:

1. Being an UPstander

Once we’re clear what we mean when we say “bullying,” we can begin to imagine interventions that actually have measurable impacts on the problem.

I’m not sure where I first heard the term UPstander. It may have been Facing History and Ourselves, a fantastic resource for teachers that uses the term, or from the National School Climate Center, but the term is perfect.

It transforms the language of “bystander” into a call to action: Stand UP to bullying behavior!

And pairing this language shift with tools for all stakeholders in our communities can profoundly impact whether or not they join others in concerted action toward building inclusive community.

In my research for the UPstander Intervention Training for CivilSchools, one thing became increadibly obvious to me: We have to offer people lots of entry points at which they can start speaking up for positive culture and speaking out against bullying.

Our approach, then, is to break being an UPstander into three vital roles: Social Norming, Interrupting, and First Responding. Each offers a different type of action and level of commitment in being an UPstander.

To truly transform a community into one where bullying is no longer a vexing problem, there need to be people who are filling all three of the roles.

2. Social Norming

The idea of participating in Social Norming (or being a Social Normer) builds upon social norming sociological theory.

In short, social norms are flexible, changeable, and bullying exists often, or at least in part, because there is a certain level of social approval of bullying behavior.

When there are not enough empowered people standing up for the kind of positive community they want to see, even if a majority or a critical mass doesn’t support the negative stasis of bullying behavior, then bullying unfortunately gets tacit approval.

Thus, one of the most powerful things we can do as individuals is to get organized with others who want to see a different kind of community and work to change the backdrop against which bullying takes place.

Getting organized, though, requires that we have enough people on board – a critical mass – so that it’s not just you making a stink by yourself.

Social norming, then, calls for us to do the difficult work of changing the social norms that tell people that speaking out against bullying is unacceptable or uncool, that tell people that bullying is normal and will always be around, and that tell people there’s nothing they can do to build positive school culture.

Social norming must take place on two levels: passive and active. Passive norming refers to using clever messaging in things like posters or t-shirts to spread your message.

Active norming, on the other hand, describes the behavior you and others can exhibit to shift the tide of what is and is not acceptable, “normal,” within your community, which leads us to the second way to be an UPstander.

3. Interrupting

Unfortunately, the passive work of social norming is not enough by itself to make our communities more inclusive of all people.

We need a skillset of tools for interrupting bullying behavior when we see it, whether it’s happening in our schools, our locker rooms, our workplaces, or on the Internet.

While it may seem obvious, what makes interrupting difficult is finding a way to stop bullying behavior without making things worse for the person being bullied.

Additionally, it can be important to interrupt the bullying in a way that doesn’t necessarily make the person doing the bullying defensive so that there’s room to address it with them later.

Sometimes that means calling out the behavior while calling the person demonstrating bullying behavior in to live their values, i.e., “Come on, man. I know you’re better than that! Leave them alone.”

Other times interrupting means simply distracting the person who is doing the bullying so that the target gets a respite. “Hey, did you see the Broncos this week? RIDICULOUS!”

Still other times interrupting means directly addressing the person’s hurtful or problematic language and behavior so that those standing by, wishing they could interrupt, are empowered to know that someone can actually stand up.

Unfortunately, there is no simple handbook for interrupting bullying behavior, and each person has to decide what will work best for them and for the particular relationship we have with the person doing the bullying.

But the empathy it takes to see ourselves in a person being targeted for bullying and to act to intervene is central to any bullying prevention initiative, and when we reach a critical mass of people acting to help one another, we will see powerful transformation in our communities.

But interrupting by itself is also not quite enough to prevent future bullying from occurring.

4. First Responding

There are few people that I admire more than our first responders: the people who show up first after an accident, that attend to the trauma people have experienced or witnessed, that put their own lives on the line to help those who have been hurt.

We could all learn something from them, but I don’t just mean in a hypothetical sense. Their work can be directly applied to bullying prevention and response.

When I was in middle school, I was bullied quite badly. It got to the point where I was considering suicide (though I didn’t tell anyone). The few friends I had had to bear the brunt of my depression and frustration, as I turned around and bullied them in turn.

I remember this one day in seventh grade when some kids cornered me on the playground and made fun of my smile (I have an enormous smile – all teeth and gums) before jumping into a deluge of homophobic and sexist slurs.

It left me feeling defeated.

Despite a few friends trying to cheer me up, I felt alone (“They’re my friends! They have to say that,” I thought).

Later that day while standing in line for lunch, I realized that I had accidentally been caught staring at the coolest eighth grade girl in school. Her name was Audrey, and man was she cool: haircut, fashion, friends – she was perfect (in the mind of a seventh grader)!

Well, after catching me staring, Audrey came over to me and told me she had seen me being made fun of that morning.

“Great,” I thought. “She missed her chance earlier, and she wants to get in on it now.”

“You shouldn’t listen to them,” she said. “You have the most beautiful smile in the world. Forget about them.”

Then she walked away.

That was the one and only conversation I had with her, but it sure did it have an impact.

A complete stranger, one who I knew didn’t have to risk her social status by doing so, reaffirmed me, reminded me that I am okay, that I shouldn’t let the poison of the bullying inside. In doing so, she planted a seed.

It’s not like things turned around over night, but her words along with the words of my friends and family helped me to get through. Over time, with my attention and the careful attention of those who loved me, the seed Audrey planted grew into some modicum of self-confidence.

Audrey was a first responder. She showed up after a scene of trauma and helped someone who was hurt.

Now imagine if we had communities full of Audreys.

The call to be first responders is to follow up with those who are involved in a situation of bullying to help them heal, to remind them that they are loved and okay.

Sometimes first responding is best done by a loved one, and other times it’s best done by a stranger. But we need more first responders.

And we don’t just need them for those who’ve been targeted by bullying. We need them for those who have been exhibiting the bullying behavior. Researchers like Barbara Coloroso help us understand that bullying is not as simple as “she’s a bully and a terrible person.”

Much bullying behavior stems from some trauma, insecurity, or hurt that someone experiences elsewhere in their life. Is it any wonder, then, that I was a pretty big bully to my friends?

In addition to reminding those who are being bullied that they are loved and valued, we need to reach out to those doing the bullying to find out what’s going on in their lives that’s making them act so terribly to other people.

After all, we can’t stop the cycle if we don’t address the root causes of why bullying is taking place.

5. Banding Together, Transforming Community

Whether we’re participating in a social norming effort, actively interrupting bullying behavior, or reaching out to those affected by bullying, we need to recognize that we can’t do this alone.

One thing is clear to me: The vast majority of us don’t want to see bullying tear apart our communities or hurt our young people any more.

But to build the kind of communities where bullying is not a problem requires us all to play a role.

We all have to stand UP to bullying.

***

Click here to receive your free Bullying Survival Toolkit: 10 Steps to Building a Bullying-Free Culture for actions you can start to take today!

***

[do_widget id=‘text-101′]

Jamie Utt is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism. He is the Founder and Director of Education at CivilSchools, a comprehensive bullying prevention program, a diversity and inclusion consultant, and sexual violence prevention educator based in Minneapolis, MN. He lives with his loving partner and his funtastic dog. He blogs weekly at Change from Within. Learn more about his work at his website here and follow him on Twitter @utt_jamie. Read his articles here and book him for speaking engagements here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more