Source: A Girl in Transit

(Article has been translated in French here.)

Sometimes, when people piece together that I’m both a feminist and a teacher, they have a very adverse reaction to it.

“But you can’t bring that man-hating, socialist dogma into the classroom! It isn’t your job to instill values into our country’s children!”

Whoa.

Let me be clear about something from the get-go: If what you’re teaching in your classroom doesn’t directly positively affect the learning environment and the knowledge and skills of your students, you’re doing something wrong.

So, on the one hand, I agree that inserting random lectures about oppression and subjugation into your lesson plans might not make sense, given your content area.

But I also want to be clear that values-free education does not exist.

The “it isn’t your job to instill values” and “you can’t bring your ideals into the classroom” arguments actually hold very little ground, especially when coming from vehement anti-feminists who are just nervous that someone might actually (gasp!) attempt to dismantle kyriarchal structures in one of our society’s most dominant one: Education.

But the truth is that even something as seemingly insignificant as deciding what does and doesn’t belong in our curricula is a statement about our values.

Adhering to the literary canon? Running pregnancy prevention programs? That one teacher in my English department at an Atlanta high school who told her World Literature students that the Bible isn’t literature because it’s fact?

Values.

And whether we like it or not, our students are listening. They’re watching. They’re learning – and not just the material that they need to pass state exams.

They’re learning how to navigate and interpret the world – from you.

So if you’re a feminist and you want some ideas on how create a more feminist classroom (without, you know, wearing your “Clitoris is Not a Dirty Word” t-shirt on dress-down day), here are five efforts that you can endeavor.

1. Recognize and Analyze Power Dynamics

I am a white woman who historically has taught in urban schools with mostly Black and Latinx students. As if being the only white person in a room doesn’t give me enough social capital, I’m also the only authority figure.

That’s a lot of power.

Wield it effectively.

The first step? Working through your own “stuff” before you attempt to help others work through theirs.

Understand this: The process of unpacking privilege is a journey. There is no marked “end” to self-reflection.

But change starts with you.

If you want your students to understand that power structures exist, then you have to understand that and think critically about the ways that socialization affords you privileges, especially in your classroom.

How can you level out power? Create a more democratic classroom environment.

Harry Wong talks a lot about how important it is that students create their own learning.

The reason why teaches are so tired at the end of the school day while the students are energized, he argues, is “because [students] have been sitting in school all day doing nothing while the teacher is doing all the work.”

He stresses, “The person who does the work is the only one doing any learning.”

Ain’t that the truth.

You don’t have to be the lecturer at the head of the classroom in order for them to learn. Instead, think of yourself as a facilitator of learning, rather than the be-all, end-all.

Let your students make their own discoveries, and validate the feelings that they have about them. Give them opportunities to work through their thoughts and synthesize their learning.

This creates an environment where you are not in control, thereby giving your students more power.

Besides, teaching this way employs more higher order thinking skills, which your administrators will love.

Let your students have a voice – and listen to them. They can teach you just as much (if not more) than you can teach them.

That is what a democratic classroom looks like.

To start: Ask yourself how you can use your power for good. And resist falling into the old adage that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

2. Treat Everyone with Respect

A lot of students (and teachers) scoff at the idea of setting “ground rules,” but let me make a case for how it can be useful in determining what is (and isn’t) respectful behavior.

When I do ground rules activities with students, I start with an activity around expectations.

I give them a piece of paper, have them fold it into threes, and label each section thusly: “Myself,” “My Peers,” and “My Teacher.” And I ask them to freely write in any and all expectations they have of those people if a classroom is to run efficiently.

Then I create a larger version on the board, and I ask students to share their ideas.

Unsurprisingly, Respect ends up in every single category.

Well, okay.

But what is respect? What does respect look like?

In answering these questions, we can come up with a pretty fantastic list of ground rules.

But ground rules don’t work if you write them on a piece of chart paper with pretty colored markers on the first day of school and then abandon them completely.

You have to actually use them. Make them a contract. But do so intelligently.

All of the research around pedagogy that’s been coming out recently stresses that peer education is key. Use this to your advantage!

Make sure that other students are holding one another accountable for cultivating a respectful classroom, based on the agreed upon ground rules.

But remember that this means letting them call you out, too!

Sometimes, as teachers, we get this sense that we’re supposed to be perfect, that we’re supposed to have all the answers. But that’s silly.

Displaying humility can go a long way in showing your students that it’s okay to make a mistake, so long as you handle it gracefully and appropriately.

You can even use your values around respect to dictate who and how you punish.

Notice which students you “pick on.” Are you more likely to kick a male student or a female student out of class? Which races are you more likely to assign detention to? Who grates on your nerves the hardest?

Think about it. Ask yourself why. Figure out where it’s coming from and how you can be a fairer diplomat.

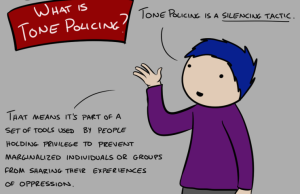

How can you address disrespectful behavior when it happens (because it will happen)? If someone in your class throws around homophobic words like f—– and d—, is it going to be more effective to write them up or to have an honest conversation about homophobia and heterosexism?

One thing to try is a values clarification activity – like “Agree/Disagree” or other “Forced Choice” options.

You may not change the behavior overnight, but you’ll give your students something to chew on that’s more guided than “While you’re in in-school suspension, write me an essay on why what you did was wrong.”

It’ll also help you understand where they’re coming from.

And before you make an argument that you can’t take time out of your day to do anything that doesn’t adhere directly to a state-mandated standard, let alone actively build a better classroom environment in this way, take another look at your standards.

Often, there are standards that deal with class discussions, communicating effective arguments, and expressing beliefs.

Mutual respect is something that students appreciate. Practice it.

3. Make Sure Marginalized Voices Are Represented

Many states and school districts (thankfully) are moving away from content-based standards and toward skills-based education.

Essentially, what that means is that educators are starting to recognize (finally) that what’s important for our students is that they learn skills, regardless of where they come from.

Macbeth? Twilight? Doesn’t matter. So long as students can identify and create metaphors.

And while there are certainly cons to moving away from The Canon, there’s a lot of good here, too.

It means that educators have more freedom to choose texts and materials that they think will work for their students, rather than adhering to strict guidelines created from bygone education standards.

And considering that our Canon is more or less a group of old, white, cishet dudes (with a few women and people of Color thrown in every now and then to prove that yeswearediverse!), this movement toward skills opens up a lot of doors.

Use this liberty to represent more marginalized voices!

You can do this easily just by bringing in new material to supplement those that don’t offer a variety of perspectives.

Because let’s be honest: While some materials try hard to be inclusive, others think that inclusivity looks like having a blurb in the corner of the page addressing a marginalized voice that is all but ignored by readers. Or, perhaps, as did my Spanish textbook in high school, randomly inserting an illustration of a person in a wheelchair every few chapters.

Nice try, textbooks, but here’s a newsflash: The notion of “separate, but equal” is bullshit.

For example, at this point in my career, I teach sex education. And going through most of the sexuality education textbooks that I’ve used, you’d think that only white people have genitals. And that’s a field that actually openly talks about intersections of identity!

Representation matters. So make sure that your materials show a wide range of people.

And use media literacy education to discuss why our educational resources look the way that they do.

Need some ideas?

In history class, allow students to do independent projects where they bring in supplemental material about what oppressed groups were experiencing in these times to help fill out the hegemonic voices of history we’ve heard since kindergarten. And talk about the effect that whitewashing history has on our collective consciousness.

In math class, use the lesson at hand to discuss how many able-bodied people are represented in the text or the variety of name origins used in word problems. Use percentages, ratios, and graphs to illustrate points about representation.

But, while thinking about how to bring in more marginalized voices, here’s one trick to avoid at all costs: Do not expect marginalized students to “represent” their group.

Instead, be the ally who brings up the perspectives that are missing from the classroom.

4. Encourage Students to Analyze New Perspectives

But remember what I said earlier about the importance of students creating their own learning: Just because you should be the one making sure that marginalized voices are represented doesn’t mean that you can’t encourage students to actively analyze new perspectives.

One way that you can do this is by introducing media literacy into your classroom. Because as much as we don’t talk about it in this sense, media literacy also applies to curricula and texts.

Who is creating them? Who is in charge? Who benefits? Are the messages helpful or harmful?

These are all questions that you can encourage students to use when they think critically about the material in front of them, with the hopes that they’ll take those skills out into the “real world,” too.

You can even create an entire unit based on media literacy and looking at material from new perspectives.

When I taught high school English, I did lens readings with my students, using clips from Disney movies as our material for analysis. I taught them briefly about feminist and critical race theories and asked them what they saw in these films through those lenses.

And I watched their jaws drop.

They started making connections and drawing conclusions they may not have been able to, had they not been given the tools to see through a different set of eyes.

Not enough time to do a whole unit? No problem!

Push students outside of their comfort zones by having them analyze how people who are different from them might feel about certain concepts or how texts would be different if identities (race, gender, orientation) were changed about a character or figure.

You can do lens readings and critical analysis in all subjects – not just English! – from history to science.

You can even do it casually.

If, for instance, in an “Agree/Disagree” game, the entire class shuffles to one end of the room, talk about why maybe a person would disagree with that statement. Challenge students to come up with reasons why a person might disagree with them.

Students will rise to the expectations that you set for them – so set them high! You might find yourself surprised at how much they can accomplish and how deeply they can think.

5. Lead by Example

It’s true: We don’t necessarily become teachers with the hope that we’ll be role models by proxy, but it happens.

So instead of shirking off the responsibility, like many celebrities do, with a statement like “Well, I don’t want to be a role model,” embrace it and use it to the advantage of your students.

Because the truth of the matter is this: Adult figures matter in students’ lives. And they spend most of the day with you and your colleagues. So make your very existence a learning experience.

That doesn’t mean that you need to be perfect. Quite the opposite, actually. Be human.

Make mistakes. Get called out. Apologize.

Be someone that they can learn from – not just because you have degrees and licenses and a job title.

And let small victories be just that – victories.

I once had a ninth grade English class who threw the F-word (not fuck, the other one) around like it was “the.” Always, I’d ask them not to use that word. And always, they’d half-heartedly mumble, “Sorry, Fabello.”

But one day, I had really had it. And so I gave them a mini lesson on the etymology of the word and why it was offensive.

And the next day?

The next day, one of my students came in and excitedly told me that while he was playing video games the night before, he thought twice before hurling the word at his opponent.

“I remembered what you said, and so I didn’t call him a f—–,” he said. “I called him a son-of-a-bitch instead.”

And so I smiled because I appreciated his effort, and I thought to myself the one thing that teachers really, truly do not hear enough, that I am now reminding you of right now: You’re making a difference.

***

A feminist classroom doesn’t have to look like a place where posters representing intersectionality are hung up next to “Smash the Patriarchy!” banners, where you spend more time analyzing the slut-shaming in The Scarlet Letter than the symbolism, where you refuse to use bio textbooks that subscribe to essentialist language – although it can.

A feminist classroom is simply a place where our values concerning equality, respect, and representation are apparent.

And when we put forth effort to create a healthy environment like that, we cultivate feminism.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Melissa A. Fabello, Co-Managing Editor of Everyday Feminism, is a sexuality educator, eating disorder and body image activist, and media literacy vlogger based out of Philadelphia. She enjoys rainy days, Jurassic Park, and Taylor Swift and can be found on YouTube and Tumblr. She holds a B.S. in English Education from Boston University and an M.Ed. in Human Sexuality from Widener University. She is currently working on her PhD. She can be reached on Twitter @fyeahmfabello. Read her articles here and book her for speaking engagements here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32