Reflecting upon the reactions to the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, it’s clear that many white people in the United States still don’t understand how fundamentally different life is for people of color.

Asserting their own “colorblindness,” most tend to think that racism is limited to organizations like the KKK — maybe certain police forces and the owners of some NBA and NFL teams are racist, but they’re the exception to the rule.

But when white police officers continue to shoot unarmed black teens and when powerful white men continue to make racist remarks, we should be asking ourselves “Why?”— not shaking our heads at the actions of a few “misled” individuals.

Because less publicized forms of structural racism continue to be expressed in everyday ways throughout the United States.

My Experiences

My name is Andrew Hernann, but it wasn’t always. The son of an Anglo mother and a Puerto Rican father, my original last name was “Hernandez.” But after I was born and my parents saw that I was lighter skinned, they decided to Anglicize our last name so that I wouldn’t face the same discrimination that my father has encountered throughout his life.

At 18 months old — as my parents like to tell the story — the three of us went to the courthouse. And after asking a few questions, the judge (bouncing me on his lap) sanctioned the name change. Happy and relieved, we exited the building different than we had entered: We weren’t Latinx anymore; we were white.

My light skin and Anglicized surname made it relatively easy to conceal my multi-ethnic identity. And growing up in a town with little racial or ethnic diversity encouraged such blending in.

I remember, for instance, when a new neighbor came over to my family’s house to introduce himself. He greeted my mom and then shook my hand, which I thought was cool because he was an adult, and I was only 12.

Afterwards, he pointed at the man mowing the lawn. Not realizing that it was my father, he contemptuously asked if “the Mexican came with the house.”

“No, that’s my husband,” my mom said.

I appreciated my mother’s stern reply. Nonetheless, it was a shameful lesson: Despite my lighter skin, as my Puerto Rican father’s son, I remain racially inferior.

Regardless of such lessons, I began asserting my Latinx identity more openly as I aged. I did this because it felt like I had been rejecting my family by not owning up to it.

I also felt proud of the advances that my dad had made, as well as my own successes. I wanted people to know that it wasn’t just a white person who was getting good grades, competing in track and field, and so on.

I quickly learned, though, that it’s not that simple.

Despite my high marks, some of my classmates — demonstrating racialized contempt for certain professions — insisted that I could/should only cut grass for a living. Later, a white friend (who ironically had declared himself an English major) accused me of taking the “easy way out” for deciding upon a Spanish degree. Others reduced my college acceptances to nothing more than the misguided results of affirmative action.

Over the years, my reaction to the name change has differed. In primary school, I thought my dad the courageous hero who’d sacrificed his identity so that his children might have a better life.

In secondary school, I thought him to be someone who lacked the guts to spit in the face of ignorance and prejudice. In my mind, he had forsaken his ethnicity and his family, taken the easy way out, gone into hiding.

That changed when I went to college.

My alma mater, the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign), has had a long history of racial insensitivity.

For instance, my senior year students threw a big “Tacos and Tequila” party; most of the predominantly white attendees dressed as Latinx caricatures. There were “illegal immigrants” and “pregnant teens,” as well as Mexican flags converted into skirts, halter-tops, and so on.

I couldn’t believe it. Confused and frustrated, I began reflecting on such blatant and unapologetic expressions of racism. I began reflecting on my last name. I began reflecting on my dad’s and my experiences with prejudice.

Suddenly, overwhelming sadness and disgust saturated my body. Seeing myself as generations of racists saw my family, I felt ugly, contaminated, and worthless.

I remember it so clearly. I rushed back to my dorm room, called my dad, and spewed:

“I’m so sorry. I thought you were a coward. I really thought you were a coward! But you’re not. You changed our last name because you felt dirty. Because you had to. Because you’re not white. It wasn’t even a choice.”

I described my encounters of campus racism and a lifetime’s worth of being devalued and othered. Then, I wiped hot tears from my cheeks as I waited for my dad to speak.

“No, I’m sorry,” he finally said. “I’m your dad. I was supposed to protect you. That’s why we changed our last name, so you wouldn’t experience what I did growing up. I was supposed to protect you, but I couldn’t.”

I imagine in that moment of powerlessness, my father felt even more worthless than I did.

I do not share these experiences to throw myself a pity party. I do not share them to victimize minority groups in the United States. Nor do I share them as an attack on white people.

I share these experiences as a way to reflect upon systematic racism and white privilege that is neither over and done, nor is it confined to the likes of certain organizations or a few “bad apples.”

So, what should we do? How can we come to terms with pervading, systematic everyday racism?

1. Acknowledge That Racism and White Privilege Exist

It is important for others to comprehend the implications that systematic racism has on individuals of color. Devaluing academic accomplishment, trivializing minority experiences and voices, and so on have real world implications at school, in the workplace, at the bank, on the street, and in the courthouse.

Indeed, compared to their white counterparts, people of color continue to receive fewer opportunities for academic or professional advancement. They regularly receive higher interest rates and have more difficulties obtaining credit.

They suffer systematic racial profiling through intensified police surveillance in non-white neighborhoods. They receive harsher prison sentences.

Anglo-Americans must acknowledge that people of color continue to encounter racism, and that that racism negatively affects the individual. Further, they must acknowledge not only that white privilege exists, but also that they have benefited from it.

2. Stop Equating White with Good

I have many conversations with well-intentioned, white progressives about race and racism. Many of them are even family members and friends. At the beginning of such conversations, I frequently hear, “Oh, Andrew, I always forget that you’re Latinx.”

When I ask what they mean, many initially claim some form of “colorblindness.” But, as the conversation continues, they reveal something else.

People often forget that I’m Latinx because I don’t “act Latinx.” Or they suggest that I’m a “good Latinx.”

Such comments are not meant to be racist. Indeed, they’re intended as compliments, as a way to smooth out racial tension. Nonetheless, these remarks are incredibly prejudicial and belittling.

When someone claims that a person is “good” because they don’t “act” Black, Latinx, and so on, what they’re really saying is that this person is good because they are acting white.

Behaviors, values, and practices associated with white individuals become the standard by which others are measured. When this happens, it becomes impossible to undermine the negative stereotypes associated with people of color.

When “goodness” equals “whiteness” — or, at least when “goodness” is seen as uncharacteristic for a given racialized community — the achievements of non-white individuals fail to improve racist conceptions of minority groups.

Conversely, when certain “bad” behaviors remain racialized, those behaviors come to characterize people of color.

The result of this is the pigeonholing of people of color. Their successes don’t prove wrong the popular conceptualizations of minority groups. Instead, these successes are (mis-)interpreted as their “getting out,” of their “escape” from a dangerous or morally degenerate community.

If minority success were allowed to feed back into minority communities, it would improve how we think about them. But that’s not what happens.

Instead, American society retains racist notions of people of color because it fails to associate “success” with them.

We must recognize that the negative connotations associated with different racialized groups are the historical products of Anglo-Americans determining the standards by which individuals are socially evaluated.

As such, we must commit to doing the mental and emotional work necessary to stop conceptualizing the successes of an individual of color as exceptional.

We need to allow communities of color to take credit for its individuals’ successes, and we need to allow them to do so on their own terms, not based on the terms established by the white community.

3. Listen

Because whiteness becomes the standard by which we evaluate success and goodness, those values and expressions indigenous to communities of color — but which deviate from values and expressions more common to white people — remain undervalued or even denigrated.

Among my extended Puerto Rican family, for example, even though many of us are English language dominant, it is important for us to use at least some Spanish phrases in our everyday conversations. This helps to preserve a sense of Puerto Rican community and more effectively express certain ideas.

But outside of the Latinx community, this practice is met with scorn. Non-Spanish speakers regularly demand that Latinx individuals “speak English or go home.” Others ridicule us by using “mock Spanish,” pseudo-Spanish phrases such as “hasta banana” or “el cheapo.”

Clearly, privileging English in American society is oppressive, and mocking the Spanish language is offensive.

When I bring this up with my white interlocutors, though, I am often accused of being overly sensitive, of playing the “race card” or of promoting a political correctness that supposedly forces everyone to walk on eggshells.

Referencing their purported colorblindness, their “one Latinx friend,” or the fact that a Black man now sits in the White House, they insist that I am the one with the problem, not them.

These are expressions of white privilege, however. And they are very telling. In my experience, it is rarely my friends of color who criticize political correctness, assert the value of colorblindness, or claim that racism is dead.

These are claims that white individuals have the luxury to make, for they are not regularly confronted with racialized social barriers.

We should all listen to what individuals of color have to say instead of critiquing political correctness or accusing one of “playing the race card.” Such critiques only serve to further undermine minority voices rather than valuing them as equal participants in an ongoing conversation about race in the United States.

4. Start a Conversation

There are many well-intentioned individuals out there. Some have benefited from their privilege. Others have been on the opposite end of it. Nonetheless, adopting either an unyielding defensive or aggressive strategy towards one another is not the way forward.

Instead, we must all commit to open dialogue about our experiences. If we all more effectively communicate and listen to one another, we can better empathize with each others’ positions.

This is a positive step in resolving ignorance and converting privilege and good intentions into effective action that can actually destabilize pervasive racism.

***

If such an open and honest conversation about race were taking place when I was a toddler, perhaps the name on the by-line of this article would read “Andrew Hernandez.”

Because that’s who I am — who my family is — faults, failures, accomplishments, and all. And I, for one, want to live in a country that recognizes and celebrates this.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

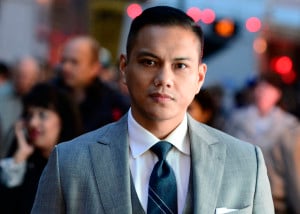

Andrew Hernández is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is a public anthropologist and teacher. He is completing his PhD in cultural anthropology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and he adjuncts at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY) and Baruch College (CUNY). Andrew bases his research out of West Africa and the Sahara, working on issues of human rights, labor and religion. In his spare time, you can find Andrew placating his dog, Pip, who he’s convinced is an evil genius. Follow him on Twitter @AndrewHernann.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32