Source: Driver Layer

With the exception of, perhaps, Oprah Winfrey, no Black person in the United States has been used as an example of racial progress as much as President Barack Obama.

This example is so weary, its youthful hairs turned gray long before Obama’s did.

Chris Rock recently turned this example on its head when he asserted that Obama’s election is not a sign of Black progress but, rather, a sign of “White progress.”

There have long been Black people qualified to run this country — Frederick Douglass, Shirley Chisholm, Thurgood Marshall, Audre Lorde, Beverly Daniel Tatum, to name a few — but it took until 2008 (232 years later) for a White-dominated electorate to allow a multiracial candidate access to the country’s highest office (one who had to dodge race as much as he could during his presidential bid to keep such an electorate comfortable).

Six years after that historic election, in the wake of not one, but two grand jury decisions to not indict White police officers who killed unarmed Black men — as well as the subsequent reactions by many White Americans to minimize, deflect, and deny the role of race in the events — it’s time to ask:

How much progress have White Americans really made?

My exploration of this question is not intended for all White people. It is not for White activists, those constantly looking for productive outlets to channel their outrage, nor White supremacists, those more likely trolling Everyday Feminism instead of learning from it.

Rather, this article is written for those who dislike racism, yet do little — if anything — to resist it.

It is written for those who sit on the edge of action, but don’t yet know how to get up. If they watch The Daily Show, they might have seen Jon Stewart’s interview with professor and author Bryan Stevenson.

Stevenson contrasts Germany’s response to the Holocaust to the United States’ responses to this country’s greatest stains (slavery, Indian removal, Indian boarding schools, Jim Crow, Japanese incarceration, and mass incarceration, to name a few).

As evidence that Germany requires its citizens to confront their history, he states that “there are monuments and memorials and there are totems to make you have to deal with that.”

As a teacher, I have witnessed German exchange students vehemently shut down American students’ flippant use of the word “Nazi.” To these exchange students, there could not be a worse insult.

To many White Americans, the word “racist” ignites similar ire, often unleashing the most primal of defense mechanisms. Yet, in contrast to Germans, most White Americans have done little to face their history and its legacies.

Unfortunately, the consequences of not doing so are profound.

Here are two significant ways in which White Americans lose when they opt to lock their car doors or cross the street instead of facing their own racism.

1. Their Worldview Is Completely Skewed, Resembling Fiction Far More Than Reality

Author and Spelman College president Beverly Daniel Tatum contends that the culture of racial silence amongst White communities creates oblivious, disconnected White people.

In Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?, she writes, “A significant dimension of who one is in the world, one’s whiteness, remains uninvestigated and perceptions of daily experience are routinely distorted.”

They, essentially, become Neo, stuck in the opening minutes of The Matrix, long before any offer of red or blue pills, not yet perceiving “The Matrix” for what it really is.

In our universe, too many White Americans overestimate crime rates of people of color (sometimes by 20-30%). Too many White Americans overestimate the fairness of police officers toward Black Americans.

Too many White Americans overestimate the state of health for Black Americans. Too many White Americans overestimate the pain threshold of Black Americans; too many White Americans overestimate the age of Black children, a mistake that cost twelve-year-old Tamir Rice his life.

And too many White Americans underestimate income and wealth disparities between White and Black people. The list goes on. And on. (And on.)

Note that the data here are Black-centric because of the wealth of articles published in the aftermath of Darren Wilson’s killing of Michael Brown and Daniel Pantaleos’ killing of Eric Garner.

But White Americans’ twisted perceptions are not limited to Black Americans.

As yet another tired way of evading responsibility for racism, White Americans often point to the supposed success of Asian Americans, not knowing, for example, that Asian Americans need SAT scores 140 points higher than those of their White peers to enter the nation’s top universities.

Or that between 2006-2010, according to Colorlines, the number of Californian Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders living below the poverty line increased 50%, while their unemployment numbers jumped by nearly 200%.

Or that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have “the highest long-term unemployment rate of any group in America.” Again, the list goes on.

Not only do many White Americans remain oblivious to their advantages and biases against people of color, they also incorrectly believe that they are the ones who are disadvantaged — especially when it comes to admissions and employment opportunities.

Yet, in pretty much every institution (except for the prison system), people of color are underrepresented, often grossly so.

It is far more likely that the person taking the spot other White people feel entitled to is White, not a person of color.

Nonetheless, too many White Americans insist on remaining oblivious to the pill option – or scarfing down the wrong pill.

2. They Live in a Constant State of Denial

Denial may seem like a quick short-term fix, but it is actually a form of delusion — not the actual solution to benefiting from racism and white privilege.

There has yet to be a hero who has won the day in a state of denial.

Luke had to accept that Darth Vader was his father before he could bring him back to the white light side of the force. Katniss had to accept that she was the Mockingjay before the revolution could—well—catch fire. Reality is no different.

Denial has never served me in love, life, or work — and oh boy, especially not in distance running.

In fact, the denial of mild cold symptoms during training led to an extended bed-ridden road to recovery. The denial of tendonitis during training led to a slow-healing stress fracture.

If denial in small doses is so deeply damaging, what is the impact of outright, systemically complicit denial?

In the documentary The Pathology of Privilege, anti-racist educator Tim Wise — who, ironically, has recently been called out for his own misuse of white privilege (which further goes to show that deprograming ourselves of anti-black racism is an unending process) — demonstrates the depth of White denial. He provides polling data from 2007 which shows that only 6% of White Americans categorized racism against people of color as a “significant problem.”

Wise then reveals that in polls from the early 60s — a time nearly all White Americans would now agree was “profoundly unequal” — White Americans responded with strikingly similar numbers as they did in 2007.

As Tim Wise points out, every single generation of White people throughout this country’s history has misjudged the presence and power of racism.

If denial runs so deep that it can span generations and generations of White Americans, exactly how destructive are White Americans being to themselves?

While I don’t have the answer to this question, any therapist will tell you that when facing a patient in such an extreme state of denial, the question merits further, persistent, and urgent exploration.

Perhaps more White Americans would become more invested in the fight for racial justice if they looked inward to question the costs of their denial.

***

Luckily, there are some concrete steps you can take that not only counter these costs but also counter racism — a win, win situation.

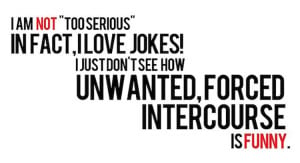

1. Change Your Relationship with the Word ‘Racist’

Dissociate “racist” from images of a burning cross, the white pointy hats, and flowing sheets. As I argue in my previous article, racist messages are everywhere.

The question isn’t how could you be a racist but, rather, how could you not be racist?

Beverly Daniel Tatum compares racism to smog. We are all breathing it in; we are all affected.

If you think the only White people who need to be concerned with racism are White supremacists, you are missing the point — many points, actually, as several have reiterated this message.

In the famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote back in 1963, “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s greatest stumbling block in this stride toward freedom is not the…Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate.”

In other words, if Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. were alive and imagining current barriers to racial progress, he might be imagining someone who looks more like some of the readers of liberal, justice-oriented news sources than readers of White supremacist sources like Stormfront.

2. Now That You Have Made Peace with the Term ‘Racist,’ Get a Shovel and Start Unearthing Your Own Racism

Negative stereotypes of people of color are everywhere, so it shouldn’t be too hard to identify those you have internalized. It’s not fun. It’s not comfortable. It’s not easy.

But it’s honest, and honesty is a value we can all get behind.

For example, when working out at my gym in a primarily White Seattle neighborhood, I notice that the sight of a Brown or Black person immediately triggers me to consider the safety of my locker’s contents. Did I remember to lock it?

After decades of racist training, these racist thoughts are automatic.

But I can’t address how ridiculous these racist thoughts are until I acknowledge their place in my consciousness. My racist response is automatic, but so has my anti-racist training become to counter it.

A good subsequent step to acknowledging your stereotypes is noticing every time they are not reinforced — every time a Black or Brown person has not robbed my gym locker, which is every time.

Doing so will prove how absurd the vast, vast, vast majority of stereotypes are.

3. Don’t Just Acknowledge Your Privileges, But Actively and Constantly Seek Them Out

No matter how many times you review Peggy McIntosh’s many examples of White privilege, more are lurking and they constantly scurry away from consciousness.

Every time you drive by a police officer, every time you decide not to deal with a friend’s racist comment, every time you lend your credit card to a White friend or family member to use, every time you are annoyed that a protest calling for racial justice has interrupted your holiday shopping.

4. Reconcile with Your (And This Country’s) Past

Perhaps Americans need the issue framed in a way they better understand: money.

In the “I Have a Dream Speech,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. compares the oppression of racism to receiving a bad check, marked with “insufficient funds.”

In The Pathology of Privilege, Tim Wise relies on a similarly financial analogy when arguing that White Americans need to take responsibility for their racist history.

If a chief executive officer took over a company, it would be unheard of for the CEO to use the company’s assets and income but ignore its debts.

But that is exactly how White Americans have handled our history, benefitting from the legacies of racism without ever paying off our debts. (And no, guilt isn’t currency.)

Clearly the United States government is not erecting ubiquitous “monuments and memorials,” as Germany has done. In fact, in Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong, historian James Loewen challenges the accuracy of many of the totems that do exist.

But we don’t have to wait for the government’s lead.

Two clear next steps to further “White progress” are 1) calling for a truth and reconciliation process to atone for the past and 2) joining the movement to end racist police practices against Black Americans and other people of color.

Let’s work together for a community filled with more living Michael Browns and Eric Garners and more racially conscious and compassionate Darren Wilsons and Daniel Pantaleos.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Jon Greenberg is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is an award-winning public high school teacher in Seattle who has gained broader recognition for standing up for racial dialogue in the classroom — with widespread support from community — while a school district attempted to stifle it. Creator and facilitator of the celebrated curriculum Citizenship and Social Justice, he has dedicated his teaching career to social justice and civic engagement. To learn more about Jon Greenberg and the Race Curriculum Controversy, visit his website, citizenshipandsocialjustice.com. You can also follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more