There’s been a lot of talk lately on fat acceptance blogs about what it means to be a “Good Fatty.” It seems to me that there are a lot of different kinds of “good fatties,” and each one serves its own kinda purpose. So what does it mean to be a “good fatty?” (This part gets wordy, but stick with me!)

The General Concensus: A “good fatty” is a fatty who is trying or at least believes they should be trying to no longer be a fatty. That’s a reasonable definition of one kind of “good fatty” – but before we can understand what it means to be a “good fatty,” we first have to figure out what a “bad fatty” is and how they came to be seen as bad in the first place. Like most bad ideas, it starts with money and morality.

Capitalism Requires Productivity. Therefore, a productive body is seen to be one that produces and reproduces – fit, able, and “desirable.”

So, any given society is basically just a collection of people who agree with each other about certain things. Those beliefs are standardized, but constantly shifting, and those who conform to them are included, and those who don’t are not. The basis for these beliefs is called morality, and there is a moral order to any society.

In Western societies, because we’re mainly capitalist and intent on increasing wealth, morality is most concerned with maintaining productivity. For that reason, there is a mandate for self-sacrifice and for caring for our bodies in a way that maintains their productive and reproductive potential. So basically, we are meant to be strong, able-bodied, heterosexual, and sexually desirable. Folks who don’t conform to any or all of the above have stigmatized identities and are even denied rights.

Segregation and Aspiration: You can imagine society as a large circle with several smaller circles inside of it. At the core are the most privileged, with the most power, and who benefit most from maintaining societal inequalities. The further away you get from the core, the less power and privilege you have. So when I talk later on about arguing for social legitimacy, what I am referring to is the fight to be seen as included in one of the many spheres of acceptability in any given society.

For the most part, each “good fatty” archetype that exists is basically an argument or a justification for inclusion in society’s spheres of privilege. If good fatties exist, then not all fatties are bad, and therefore, we can’t ethically be excluded from society. The problem is, whenever you define something as good, you’re automatically defining it in opposition to something else – so the “good fatty” creates the “bad fatty” – who then gets thrown under the bus. This blog is basically taking a look at the 12 Good Fatty Archetypes and asking some questions about how we might use them more critically.

Important Caveat: This blog post is an intentional oversimplification, and is also intentionally using stereotype in order to create archetypes. An archetype is basically a collection of traits and behaviors that are “typical” of a certain way of thinking. I realize real human beings are far more complex than these caricatures portray, and my intention in doing this is to create a space for discussion and conversation about how certain ways of thinking can be both wonderful and problematic at the same time.

There‘s absolutely nothing wrong with fitting into any one or more of these archetypes. Lots of people (including me) do, and that’s wonderful! It’s only when we use the merits of each to justify our social acceptability that the “good fatty” becomes problematic. It’s perfectly okay to love fashion, to be super fit and able-bodied, to be fierce. This blog isn’t meant to criticize, just to ask questions about how we might continue to seek equality without leaving anyone behind.

The Fat Unicorn: The Fat Unicorn is the first of two kinds of “No Fault Fatties.” They’re fat, but they engage in none of the typical behaviors assigned to fat people. They mostly only eat healthy foods, they are fitness fanatics, their blood tests are perfect, their bodies are strong and able. These are basically the poster fatties for the Health at Every Size movement because they hold up under scrutiny. These are the folks we talk about when we say fitness and fatness aren’t mutually exclusive. They are moral, productive citizens, exactly what society demands. Strong, healthy, hearty fatties – and if they exist, then logically, fatness can’t be universally declared a “bad thing.”

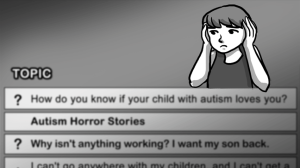

Questions to Ask: What does it mean to seek legitimacy for the fat body on the basis of its capacity for health? Who gets excluded or silenced when we do so? What makes health the primary measure of social value? Who or what systems do these beliefs benefit?

The (F)athlete: This fatty can deadlift a bison, power through a triathlon, rock some mind-blowing choreography, or even just tear up several flights of stairs without getting winded. This is related to the Fat Unicorn but is framed more in the language of power, of physical ability and of extraordinary capability. The fat of (F)athletes may be seen as a benefit to their sport or their fat might simply be excused because it doesn’t stop them from excelling.

(F)atheletes are assumed to be highly disciplined and are therefore immune to some of the stereotypes about fatness – specifically laziness. There is a moral value assigned to the (F)athlete as they have managed to maintain a useful body.

Questions to Ask: So why is a disciplined fat body a good fat body? Who does that serve? Why is fatness in service of utility exonerated? Who benefits most? What kinds of bodies specifically get excluded when we hold up the example of fat athletes in our quests for social legitimacy?

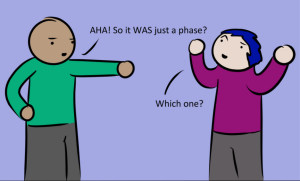

The Work-in-Progress: This is the fatty in the process of becoming not-a-fatty (however successfully). The fad dieter, the “lifestyle changer,” the gym-goer, the post-operative. This is the body under vigil: strictly disciplined, and in perfect (or imperfect) accordance with moral ideas about moderation and labor. This fatty doesn’t get the same kind of “pass” on their fatness that the Unicorn or the (F)athlete does, but they are considered a “good fatty” by the mainstream because they are in some fashion (even if it’s done with a critical political perspective) embodying the social mandates of aspirational thinness.

Questions to Ask: In what way does open engagement in the practice of dieting temporarily render existing fatness more acceptable than fatness which is fixed/stationary? When we take on the identity of a work-in-progress, what kind of privilege comes with it? What does it mean to be not in progress?

The Real Woman: The muse for “Real Women Have Curves.” This is the heroine of the Dove Beauty campaigns. She is oppositional to the stick-thin fashion model, often described as “supple” or “voluptuous,” and may even have a cheeky fat roll or two. Maligned by the fashion industry that considers her “fat,” she is proposed as merely “normal,” the new median where the everyday woman exists between the fictional figures created by beauty rags and the “truly fat” women that compose the “obesity epidemic.”

Questions to Ask: What social processes have created the “real woman?” Who benefits from the construction of “real women?” When we apply words like “real” to one type of body, who do we silence and exclude?

The Fatlebrity: The “ambassadors” of fatness. Gabourey Sidibe, Jack Black, Adele, Rebel Wilson, Beth Ditto, Melissa McCarthy. These are the ambassadors of fatness whose extraordinary artistry or performance skills create them as an exception to the general rules of social exclusion. These folks are an example in the larger sense, but these dynamics happen in everyday social circles as well. Fatlebrities are “in service” as all performers are, to the larger.

Questions to Ask: Why are some fat celebrities hounded regarding their size (Kirstie Alley, Jessica Simpson) and others heralded as ambassadors of positive body image? What forces are at work to construct some fat celebrity bodies as more acceptable than others, especially around ender? Outside Hollywood, what does it mean to be the exceptional fatty whose talents create social capital not afforded to others? and how far does that social capital actually extend?

The Mama Hen: The Maternal Fat Body. The stereotype of maternality places women’s fat bodies outside (or past) the process of reproduction, and outside of the male gaze. Non-sexualized and non-threatening, the maternal fat body exists as a metaphor for compassion and comfort. Also, the maternal figure is the one who cares for the workers – past sexual prime or robbed of sexuality altogether, she becomes another kind of laborer. The maternal fat body needn’t be an aging body at all. This stereotype works to dismantle the natural sexuality of many fat women of all ages. It can be thought of as the working assumption that, in tandem with the fatlebrity’ archetype, sets up the “joke” so often used in mainstream films wherein a fat woman’s natural sexuality is presented as comedic, shocking, or grotesque. (Think Melissa McCarthy in Bridesmaids.)

Questions to Ask: How does sexuality intersect with fatness? What creates the non-sexualized fat female body as more acceptable than the fat female body which owns its sexual nature?

The Big Man: The protector,tThe bear, the beast, the strong man, the clown. Related to the (F)athlete, but more relevant to the family. The Big Man is sometimes the unlikely hero (Paul Blart), and sometimes the sweet and vulnerable “good guy” (Dan Conner, Homer Simpson), but only ever momentarily disassociated from power. The Big Man is often associated with class – and has a life at both ends of the class spectrum, either as the poverty or working class “head of the family” or as the comically indulgent figurehead of affluence.

Questions to Ask: What creates the differences between masculine fatness and feminine fatness as negative or positive? How has masculine fatness come to be associated with power where feminine fatness has not? How does the fat male body maintain its socially sanctioned sexual desirability where the fat female body is often robbed of it? (See the Mama Hen archetype.)

The No Fault Fatty: This is the second of the No Fault Fatties. Hapless fatties are fatties for reasons beyond their control. Irreversible fatness rooted in other conditions (example: polycystic ovarian syndrome) or necessary treatment for other ailments like steroids/anti-depressants, fatness that can be proven to be unavoidable can somehow be excused. The individual will still have to deal with the same level of stigma from strangers as the underlying reasons for their fatness won’t be visible on the surface, but once the reasons are explained, the individual has the benefit of moral absolution.

Questions to Ask: What privilege is accessed through the claiming of that moral absolution? Who gets silenced when no fault fatness is used as a justification for social legitimacy?

The Dead-Early Fatty: I know, I’m sorry. This one is morbid – but we’re talking about all kinds of “good fatties,” and we’re discussing what purposes they serve. And in service of the medical and pharmaceutical industry, to put it bluntly, there is no better fatty than a dead one. Each fat individual whose death conforms to one of their obesity doom prophecies can then be enveloped into another set of statistical warnings, offering more opportunities to justify social and financial exclusions, to fund research and product development, and to create oppressive legislation.

Questions to Ask: How has science been authorized in its production of knowledge regarding the fat body? What processes are at work in the creation of scientific knowledge bout the fat body? Who benefits from this knowledge?

The Natural Fatty: She’s on the right track, baby, she was born this way. The natural fatty is fat due solely to genetics. This fatty is basically the same as the Fat Unicorn, but is talked about a bit differently within activism. Fatness, in this case, constitutes a “natural kind,” one of myriad possible and inevitable human forms existing along a spectrum of natural human diversity. Backed by medical studies proving long-term maintenance of weight loss is difficult if not impossible, the Natural Fatty exists in stubborn opposition to the similarly stubborn idea that fatness can never exist without “bad” behavior. This is the polar opposite of the worst-case-scenario fatty proposed within obesity epidemic rhetoric.

Questions to Ask: What processes within Fat Activism have created this construction of the “natural” fatty? What is its agenda? What larger structures does it echo? Who does it leave behind?

The Fatshionista: Those within a specific size range (and I’d argue body shape), with financial resources, sewing skills, and/or on-trend clothing available in their size, are able to adopt practices and identities along the fringe of mainstream fashion, even gaining mainstream acceptability in certain cases. Defying the stereotype of the “dumpy” fatty, fatshionistas celebrate their bodies with form-fitting and rule-breaking clothing and function within both Fat Activism and the mainstream as an embodied argument against ideas of poor hygiene, slovenliness, and lack of desirability.

Questions to Ask: How does the acceptability of fatness clad in fashionable clothing contribute to the mainstream beauty politic? When we argue for acceptability based on our ability to maintain? What impact does the requirement for fashion for acceptability have on those who cannot afford, have limited access to, or are uninterested in fashionable clothing? Are problematic social hierarchies and exclusions outside activism mirrored here within it?

The Rad Fatty: AKA the “Fierce” Fatty, the “Feisty” Fatty, the “Uppity” Fatty. The Rad Fatty is the ultimate rejector of stigma. Appropriating stigmatizing terms and turning them on their head, refusing conformance on every level, and often engaging in performative displays of behaviors that are discouraged in or considered stereotypical of fat people but with intention and a tone of rebellion. The Rad Fatty has a strong fat politic, has likely been involved in activism. Some have attended higher education institutions and have an academic understanding of sizeism while others have undergone a process of self and/or community education to gain their knowledge and insight. The “rad” in Rad Fatty means Radical as well as just “rad” (e.g. awesome, cool, fierce, etc.) and speaks to a commitment to undoing oppression, not only in their own lives, but in the society. There is a high value placed on political knowledge, appropriate language, and that “fierceness” that comes with an active rejection of stigma and having learned to love and appreciate the self.

Questions to Ask: What identities spring to life outside the bounds of radicalness? If social capital within Fat Activism is based on the rejection of conformance, are those who engage willingly in some self-disciplinary behaviors therefore presented as less resilient/resistant? If fierceness is presented as the pinnacle of self-actualized fatness, who gets left behind? What kinds of hierarchies does this create?

CONCLUSION:

The Good Fatty is a complex subject, and each seeks legitimacy in its own way and from its own target audience. But where we create one inclusion, we often create or reinforce other exclusions. It’s important to be aware of where and how we seek social capital and who we leave behind when we do so.

That said, I’ll take a moment to reinforce what I said at the beginning: There is nothing wrong with falling into any (or even many) of these archetypes. Sometimes I use fashion to make myself feel safer as I walk through the world, sometimes I get overwhelmed and fall back into old dieting behaviors, sometimes I strive to embody that fierceness I admire so much in other rad fatties. Again: Where the “good fatty” becomes problematic is when it’s used as a justification for social legitimacy – when it says “I deserve to be seen as valuable because (insert ‘good fatty’ qualifier here).” We all deserve to be seen as valuable, wherever we’re at in our individual journeys with our bodies, our self esteem, or our politics.

LEAVE NO FATTY BEHIND!