Source: xoJane

Originally published on xoJane and republished here with their permission.

(Trigger Warning: Mention of murder and suicide.)

“Nobody notices when we leave. I mean, the moment when we really choose to go. At best, you might feel a whisper, or the wave of a whisper, ululating down […] I was here for a moment. And then I was gone. I wish you all a long and happy life.” —Alice Sebold, The Lovely Bones

When I was 19, I read an article in Guernica magazine stating that the average life span of a transgender person is 23 years old.

The article confirmed what I had already known for about a decade: I was doomed to a nasty, short, and miserable life.

I was going to be poor, maybe homeless, definitely unemployable. I was going to be subjected to emotional and sexual violence (and in fact, I already had been), and then I was going to die, probably brutally murdered. They would print the wrong name on my grave.

You know, the good old transgender story.

I didn’t need a magazine article to tell me these things – they had already been made abundantly clear by every asshole I ever met on the school playground, on the bus, in the street.

By every 90s movie and TV special about a trans person who dies at the end. By the masses of boys and men who have been threatening to kill me since before I could define or even spell the word “transphobia.”

By my parents, who, upon hearing that I identified as female, began to cry and told me that it felt as if I had already died.

Yet there was something about seeing that reality spelled out in concrete terms, in a statistic (whether or not it was accurate), that hit me hard.

23 years old – the number is lodged in my memory.

Trans women of color are forced to live with the reality that our days are numbered. Sometimes, though, it’s nice not to think about exactly how many might be left.

This January, after years of agonizing over the personal, political, and social ramifications of “medical transition,” I decided to start hormone replacement therapy for the first time.

It’s kind of a cliché, but it felt like being born. There’s something about the decision to radically alter the physical and chemical makeup of one’s own body that makes one newly, vividly aware of being alive.

And for me, it is a joyous awareness: For years, I had believed that taking hormones was succumbing to the insidious, hegemonic narrative created by Western psychiatry that “real” trans people hate their bodies, which I could not reconcile with my own reality.

Finally, I realized that I didn’t have to transition because I hated my body. I could transition because I loved myself.

In the third week of 2015, I walked into a doctor’s office in Montreal to begin the process of starting hormones.

In the waiting room, as I scrolled through Facebook on my phone, I saw that, in the United States, a trans woman had been killed.

Six weeks later, it is the end of February and for every one of those weeks, one or more trans women/trans femmes have been reported murdered in America, the majority of them women of color: Lamia Beard. Ty Underwood. Yazmin Vash Payne. Taja DeJesus. Penny Proud. Bri Golec. Kristina Gomez Reinwald.

Two days ago, another trans woman of color named Sumaya Dalmar was found dead in Toronto, under undisclosed circumstances.

Their deaths have sent a shock wave racing through certain liberal and leftist communities; immersed as I am in leftist media, every day I see a news item, or an op-ed, or a blog post about this “wave of trans woman murders” in 2015.

My Facebook feed is a river of statuses (mostly by cis people) proclaiming rage, mourning, political solidarity. All this, mixed in with event invitations and political commentary and cat photos.

The net result I get reading it all is a sort of absurdist existentialism: Look at what my kitty ate for breakfast. A trans woman was stabbed today. Come to my DJ set! A trans girl was murdered by her family. Fuck the Academy Awards. This is how you’ll die.

It feels strange that there was, very recently, a time when dying trans women never made the news – when mainstream media simply wouldn’t report on their deaths, or would identify them as men.

Nowadays, it seems like the story of a young, tragically dead trans woman appears in the media at last once a year, almost like a sacrificial lamb to assuage the guilt of liberal cis folks who would never have known the names of those same trans women when they were alive.

The reactions are always the same: outrage, sadness, cries for change. Then nothing happens, and trans women continue to die.

In the summer of 2013, when Islan Nettles was beaten to death in New York City, I went to a memorial and lit a candle, went to a rally, wrote an article. I was vocal and impassioned, but privately I felt lost and despairing.

Last December, when Leelah Alcorn posted her suicide note on Tumblr and killed herself, I shut off my laptop and lay alone in the dark for hours.

These days, I look at the latest reports of stabbed, shot, beaten trans women, search myself for tears, and I cannot find a thing. I want to mourn and rage.

I want to honor all of our sisters – the hundreds each year who are ripped, namelessly and without fanfare, from this life – who are taken so young before their time. But the grief and anger – even empathy – do not come.

I don’t feel anything but numbness and fatigue, and somewhere far below that, fear.

The sociologist Kai Erickson once wrote that collective trauma is

“a blow to the basic tissues of social life that damages the bonds attaching people together…so that ‘I’ continue to exist, though damaged, and ‘you’ continue to exist, though distant and hard to relate to. But ‘we’ no longer exist as linked cells in a larger communal body.”

Simply put, if a group of people is traumatized – terrorized – enough, they will cease to feel connected to one another.

This disconnection is a defensive response, an attempt to shut off the pain of being associated with the group. As a result, we become withdrawn, isolated inside the story that we are alone and without hope.

I am starting to think that trans women and trans femmes – all of us linked by the cardinal sin of being named boys at birth, yet breaking the rules of boyhood and manhood – are trapped inside a traumatized story.

From an early age, we are inundated with the story of our deaths. We relive it over and over many times before we actually die.

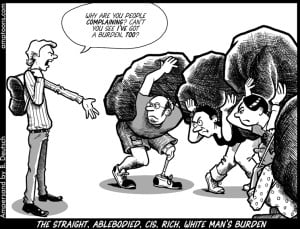

This same story is taken up, commoditized, and mass produced by communities outside of ourselves – media outlets looking for sensational stories, academics looking to produce research, and as Morgan Collado points out, even “LGBT” human rights organizations eager to use the statistics of transphobic violence to garner funds used to pursue the interests of cis, white gay and lesbian people.

Even well-meaning liberal cis people – eager to earn “ally” points – consume and exploit the narrative of the doomed trans woman in their way.

Am I saying that we shouldn’t be talking, writing, agitating over murdered trans women? Emphatically not.

What I am saying is that trans women should be given the floor when it comes to this conversation. We should be the ones to write our own story. And we should be talking about the living as well as the dead.

We should be offering young trans women just starting to think about themselves as such the hope that they will be able to live long and happy lives.

Janet Mock and Laverne Cox are wonderful “possibility models,” but they are not enough.

I want – we need – more.

More than liberal righteous anger, we need concrete funding for trans shelters, scholarships, program grants. More than nihilistic leftist rhetoric, we need creativity and transformation.

We need people to stop talking about how trans women get killed all the time. We need people to start telling us that they won’t let us die.

A week ago, I posted this Facebook status: “Every time I see an article about trans women being killed, I remember that someday I may die that way.”

Within the hour, a half-dozen cis folks had commented that they were sorry that we lived in a world where I had to live in fear. I wanted to feel touched, but I just felt dread.

Feeling sorry will not protect me on the street in the night when a man decides that I am too odd-looking to be allowed to live.

Posting articles about trans women’s murders will not stop it from happening to me. It only increases my certainty that I will be alone on that street, in that night, when the moment comes at last that my numbered days have run out.

A bit later, another friend, also a trans woman of color – and one of the fiercest, most fabulous girls in the city – sent me a private message.

In it, she promised that “it” wouldn’t happen to me. That she would protect me, somehow, some way. And reading it, I cried for the first time in this terrible year of murdered sisters.

Because no one had ever said this to me before. No one had ever cared or dared enough to make that promise: to tell me that I would live.

Young trans girls, I have a story to tell you: Ever since I was a tiny child, I knew I was girl. Everyone I knew tried to convince me otherwise, and when I refused to be persuaded, they told me I would die.

But I didn’t. I found a band of audacious sisters, and we lived, laughed, loved, even in the midst of all that hatred. I am looking for you, looking out for you. We can change this story together.

Next month, I turn 24.

***

To learn more about this topic, check out:

- Why Our Conversations About Street Harassment Need To Include Trans Women

- Getting With Girls Like Us: A Radical Guide to Dating Trans Women for Cis Women

- ‘Women-Only’ Spaces That Exclude Trans Women Lead Us Down This Awful Path

- I Think I Might Be Trans: 8 Important Notes On Questioning and 50+ Resources to Get You Started

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Kai Cheng Thom is a writer, performing artist, and clinical social worker based in Montreal. Their writing has appeared in Youngist, Matrix Magazine, and The McGill Daily, among other places.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more