Source: The Balanced Mind

I’m shopping in the mall with my father in Ballwin, MO.

I want to take a peek at some snapbacks, so we venture into Lids, and I take a quick look around. We are the only customers in the store.

Maybe ten seconds pass before I notice the two brothers behind the clerking booth holding back laughter and smiles as they gawk at me, quickly looking away once I notice them.

Immediately irritated, I glance up at my dad, who is in his own quiet, stoic zone and hasn’t noticed.

As the poorly concealed laughter and under-the-breath comments continue, I eventually have had enough and storm out of the store. I hear their laughter erupt and my father trail behind me, still unaware.

I tell him, curtly and ignoring my tears, what happened. At first, he brushes it off. Later, sensing something is wrong in my icy silence, he asks again what happened.

I’m frustrated and tell him that he doesn’t know what it’s like to be Black and queer and different in the middle of nowhere – that the men had taunted me, that I wanted to go home.

“I’m Black with a doctorate in the sciences!” he interrupts at one point, angry.

Of course he knows what it’s like. Of course he does.

And he expects me – his “daughter” – to swallow my feelings and move on, as he had so many times. So many times that he now felt nothing – or wanted to feel nothing.

Pissed that he’s made it about himself, I remain coldly silent as we file out of the mall and into the parking garage.

As we reach the car, he’s somewhat remorseful. “I’m sorry, kiddo,” he sighs quietly, full permission for me to let the tears escape.

“I can’t always react,” I say, “because if I did, I’d be pissed all the time.”

He rubs my back, his voice full of the controlled rage that I find more frightening than anger. “Because if I had heard them, I woulda kicked their asses and wound up in prison!”

I look at him and know he understands. His layers of hurt are just deeper than mine are.

Sticks and Stones Will Break My Bones – Words Will Traumatize Me

I’ve been called “too sensitive” for my entire life – you could say that I’m now desensitized to it!

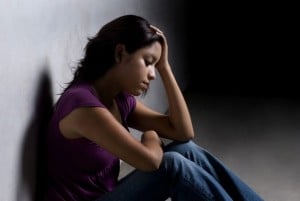

As someone socialized as female who felt deeply not only my own pain, but also the pain of others, I was an easy target.

I was taught that my tears and so-called “hypersensitivity” were shameful, and that I should learn to control it, learn to fight back.

Being sensitive, I was also an easy target in school and was bullied relentlessly. People loved to pick on me because I would be visibly upset by it, and some of these kids had no other sense of control.

Maybe they couldn’t make their own lives better, but they could hurt other people the way they hurt.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve noticed the ways in which my or others’ supposed state of being “too sensitive” has been used to justify daily microaggressions and overt instances of oppression:

A white friend became outraged when I wouldn’t let her touch my hair; a classmate claimed that racism ended once Obama was elected and that we’re “making too much fuss”; and countless other examples that show ignorance, privilege, and a lack of empathy.

And I understand on some level.

When folks who haven’t experienced a certain type of oppression unintentionally step on the toes of someone who has, it can be shocking and upsetting.

Most people I come into contact with don’t walk around with the intention of being racist, sexist, ableist, transphobic, and so on, but many others do.

If our first response to offending or microaggressing someone of marginalized identity (or an ally) is to become defensive and point the blame back at them, that shows a lack of respect and accountability that hinders relationship building.

If our first response to being asked to use more inclusive language is to complain about how we “can’t say anything anymore,” or how we’ve become too “politically correct” or sensitive, we’re suggesting that it remains the responsibility of the oppressed to accept the oppressive labels and behavior, rather than to resist it.

In most of my experiences being called “too sensitive,” what people actually didn’t like was my refusal to ignore their problematic behavior and my audacity to feel something in response to it.

I may be tender, but oppression is also cold, harsh, traumatizing, painful, unaccountable, ruthless, and ancestral.

And when you step on my toe, it may have been the fifth time that day that someone has, and it hurts much more now.

The same is true for the hurtful words, snide comments, and stares that have piled up on our backs, but that are seen as “not a big deal” to so much of the world.

These are not isolated incidents, and there are layers to our “sensitivity.”

It is ancestral, connected to deep personal pains we have experienced throughout life, and rooted in current events.

Before accusing someone who has come to you vulnerable enough to share their pain of being “too sensitive,” consider first all of what that person has been through.

Ancestry, Childhood Roots, and the Present: The Layers of Sensitivity

A white friend became outraged when I wouldn’t let her touch my hair.

It took many, many years for me to have a sense of ownership over my own hair that was not influenced by white supremacy and European standards of beauty.

As a child who was increasingly bullied, I traded in my thick braids and berets for a sleek, shiny, straight relaxer.

I was complimented and called “beautiful” more than ever before – now that I had the “good hair” to go with my already light skin. Never mind that the chemicals burned my scalp until it bled and scabbed. That was the cost of beauty!

By the time I was a sophomore in college, finally learning about true Black history and rocking the Angela Davis fro, I had finally accepted that not only was there nothing wrong with it, but in fact, my natural hair was beautiful, too.

And whenever a white hand reaches out to grab it, uninvited, I am reminded that it’s “different” or “exotic,” that white supremacy controls the beauty industry, that slaves were not allowed to care for their own hair and were forced to cover it.

Now, did my friend (at the time) know all of what lay underneath my instinctive backing away from her?

No, but she also became defensive and dismissive when I tried to calmly explain myself (which I also get sick of doing constantly).

When Black people and people of color are told to “chill” and “stop being so sensitive” about the racism thing, it tells me that there is a massive disconnect somewhere.

Not only are we being told constantly to “get over” racism so that white people can live more comfortably, but we are also being told that slavery happened a long time ago, so we should stop bringing it up.

Transatlantic slavery was horrific, traumatizing, and decimating for Black folks across the Diaspora “back then,” and we still feel its effects and see its ghosts in current times.

It is literally in our blood and ancestral heritage. Slavery is legal in our prisons, which are overflowing with Black and Brown people.

So, I beg your pardon for having an emotional reaction to current manifestations of racism!

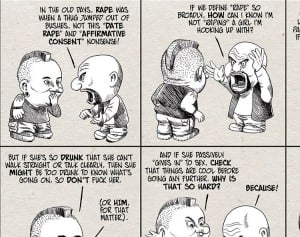

But most self-identified liberals would agree that racism is a problem in the US and abroad, while chortling over Cards Against Humanity with its jokes about the three-fifths compromise or watching Family Guy and getting a kick out of your commonplace rape joke.

And anyone who has a problem with that is immediately “too sensitive” or “victim to the era of political correctness,” right? Wrong.

A woman who is sick of being catcalled and openly harassed on the street and dares to say something about it is not “too sensitive.”

Transgender and gender non-conforming activists of color who demand accountability from LGBTQIA+ organizations who silence them and ignore the violence they are experiencing are not “too sensitive.”

Students with disabilities who rally for more accessibility at their university are not “too sensitive.”

The problem is a lack of critical self-reflection.

The problem is a lack of empathy for the histories of oppressed groups of people.

The problem is a system that allows racist fraternities and sororities to get away with blatant racism because it’s “all in good fun” or so-and-so “didn’t mean it.”

The problem is that we see individual insults or jokes as separate, isolated incidents when they are actually reflective of a toxic and oppressive society.

The problem is not sensitivity or marginalized people daring to speak out against things that are not okay – it is the indifference and defensiveness we are most often met with.

Enough Is Enough Is Too Much: The Numbing Factor

“I can’t always react, because if I did, I’d be pissed all the time.”

My father is a wise man – and he has a good point about “picking our battles” and being careful with our tenderness.

Although I don’t entirely agree with him – and take the more “If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention” perspective – I have come to understand that desensitizing is a tool of survival.

Both of my parents are tough, raised in large Black households where they learned to fight, not necessarily to feel.

And yet, I know each of my parents to be deeply sensitive and feeling people who have learned to pretend that things don’t hurt.

They have had to in order to function.

And while numbing out is a natural reaction after centuries of oppression and daily reminders that we are “less than,” I also think it is one of the most dangerous things that can happen in movements for justice and equity.

Oppression is bizarre and contradictory – on the one hand, minorities are seen as “too sensitive” or “too angry” when we object to our own suppression, and on the other, we are seen as less than human, as less likely to feel any pain.

Capitalism and white supremacy profit off of our silence, our numbness, our lack of reaction and sensitivity.

Sensitivity is not a weakness. In fact, it is incredibly powerful and threatening. And powerful emotion is one of our greatest sources that fuels change.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

MJ is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. They are a Black, queer, and genderqueer educator, activist, writer, and musician based in Oakland, CA. They believe in the power of storytelling, vulnerability, allyship, and artistic expression to build movements and community.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more