“We are moving backwards on the racial front to the point that a white person doing the basics on a clearly racist incident looks like a king.” —Dr. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

Earlier this year, a video documented members of Sigma Alpha Episilon (SAE) fraternity at the University of Oklahoma singing the chant, You can hang ’em from a tree, but they’ll never sign with me. There will never be a n—– in SAE.”

Since then, the two members of the fraternity leading the chant have been expelled, and the chapter has been suspended.

So how does this incident – and countless other racist incidents that transpire at traditionally white fraternities and sororities –translate to a larger system of racism?

Because make no mistake: These racist incidents are issues of structural racism – a system where public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work to perpetuate racial group inequity, where privilege is associated with whiteness.

Here are three reasons why.

1. Racist Chants and Parties Reinforce Racist Ideology

The SAE chant mentioned earlier has explicit similarities to white supremacist and segregationist campaigns during the Jim Crow era and carries with it the sentiment of systematic exclusion that has existed for multiple generations. The lynching metaphor, for example, evokes Black powerlessness, while the fraternity symbolizes the power and endurance of white supremacy.

The racist ideology behind the chant is that Black folk are better off dead than participants within the educational system.

With historical and current issues around law enforcement, this idea of Black folk being better off dead or behind bars is highly relevant.

And the reinforcement of racist ideology on college campuses is nothing new.

Racist parties, for example, stereotyping racial, ethnic, cultural, and historical identities (regularly and popularly) diminish the experiences of people of color. The Arizona State University chapter of Tau Kappa Epsilon had “MLK Blackout” party to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday where party-goers flashed their own versions of gang signs for photos. The diminishment of history is not lost here, as Arizona was also one of the last states to establish the MLK Jr. holiday.

Of parties, a student from Dallas, Stephanie Eyocko, says, “The kind of parties they have here aren’t really sensitive: Cowboys and Indians, Fiesta, Border Patrol,” she said. “They had a white-trash party that wasn’t even sensitive to themselves.”

Beyond insensitivity, these interactions – whether a fraternity chant or party — uphold institutional and ideological racism. Students of color internalize these feelings of not belonging, of unworthiness, of being an outsider.

And these racist incidents don’t occur just in these overt forms, but also much more insidiously.

These incidents occur at historically white colleges and universities (HWCUs). These universities, the majority of state and private universities across the United States, reproduce whiteness and white supremacy through curriculum, demography, and traditions. Racist ideology is also enacted through admissions policies and hiring practices of faculty and staff.

For example, to look at how oppression manifests on the institutional level, one can look at the proportion of non-white faculty, students, and administrative staff. Questioning who is and isn’t at universities showcases who is included and excluded from the educational institution.

For example, Rutgers University in New Jersey, nationally ranked as the most diverse university, has undergraduate enrollment has enrollment rates of 7% African American students and 12% Latinx students.

Ranked as one of the least diverse universities, in 2012, the University of New Hampshire had 8% total non-white students enrolled in an undergraduate degree program.

Although their history, image, and culture has often have been exploited for party costumes, Native American/American Indian students have only a national average of 0.4% enrollment at four-year universities.

There are also very few people of color in tenure-track faculty positions at universities. Only 9% of faculty members at universities identify as a person of color. 60% of full-time professors are white men.

This is what we mean when we say that these issues are systemic –they exist at every single level of the institution, and they perpetuate one another in a vicious, racist cycle.

These institutional inequities –from parties to who’s who in administration – manifest in everyday interactions that reiterate to people of color, “You don’t belong here.”

2. The Focus on Individual Student Action Makes Structural Racism Invisible

A few years ago, I was at a university campus that was well known to be “liberal” and “progressive.”

And yet, that year, students were pairing a popular, unofficial drinking tradition with Cinco de Mayo – and they named it “Cinco de Drinko” with T-shirts sporting party sombreros and mustaches.

Students of color organized against this event, calling it culturally appropriative, and were met with resistance.

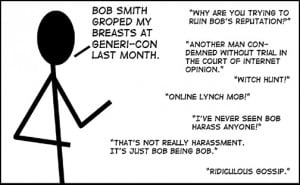

What is happening that allows many of these parties and chants to go from conception to execution, with no remorse until someone notices, and the social media jury declares it racist?

Considering how often situations like this come up, the incident at SAE is not surprising or new. It’s just that these students got caught on tape and scrutinized under the media spotlight.

As a society, we tend to focus our attention on racist individuals and their explicit actions, like saying the n-word or wearing blackface. We’re disgusted and horrified by these young fraternity men, yet less horrified and even willing to defend white people that shoot unarmed black people.

Our obsession with racists obscures the impacts of structural inequity. Examples of racism as manifestations of evil intent are easier to spot and easier to denounce, whereas institutional and structural racism is harder to observe and pinpoint.

Eradicating racists from an institution doesn’t make the institution any less racist. Racism in institutions become limited to public utterances, and we are quick to mobilize around explicit racism, but real, actual change to promote racial equity is slow progress at best.

The idea that race is a still a problem is almost unfathomable in the imaginations of nice, white people who are exempt from overt racist behavior.

Incidents where you have frat boys laughing about lynchings indicate racism being deeply woven into fraternity, university, and societal culture.

As we focus on the acts themselves the chants, the parties, the harassment –we lose sight of the actual racism. We persist in treating the structures of racism as normal, as an everyday part of culture.

We are so afraid of racists that we end up ignoring racism itself.

What does a real commitment to diversity and anti-racism actually look like? Aesthetic diversity measures that help schools appear diverse – like a splashy page on a school site – don’t indicate anything.

We can’t tackle the roots of oppression if we only focus on isolated incidents and individual racism.

Another way to look at this is to examine fraternities as institutions themselves.

3. Fraternities Are Built on a System of White Male Privilege and Power

You should read Caitlin Flanagann’s long investigative piece on fraternities’ systems to shift blame after discriminatory or violent incidents.

But the short of it is this: They wield a considerable economic, social, and cultural capital. The “boys will be boys” rhetoric is scary when we start thinking about much power these “boys” have.

Take, for example, the fact that the Greek system first emerged at elite private schools that were exclusive to the white and wealthy. Take also that fraternity traditions are rooted in the freedom to associate, a Constitutional right given by the Founding Fathers, which also happens to be a white boys only club.

This means that fraternities can choose who does or doesn’t belong in their organization. While fraternities argue in defense of a system that supports education and leadership, the larger question is: Who benefits from this system?

Establishments of social clubs for the white, rich, and male contribute to a process of wealth-creation and accumulation, educational access, home ownership, organizational leadership, and more that leave people of color behind. These organizations replicate racialized practices of who gets indoctrinated as valuable members of society.

Fraternities with mostly white members also attract not just the racially privileged, but the most economically privileged. Fraternities exhibit a considerable amount of class privilege that impact universities.

Universities often rely on wealthy donors, who come from fraternity backgrounds. 60% of donations to universities over $100 million came from fraternity alumni, and fraternity alumni also account for 85% of Fortune 500 CEOs.

The economic power that traditionally white fraternities wield overshadows the rapes, assaults, racist epithets, and violent behavior – which probably comes to no surprise to intersectional feminists with an understanding of oppression.

***

How then, do we find structural solutions to address this structural problem?

Rather than addressing these racist moments one at a time, the entire system of racism needs to be uprooted.

Rashid Campbell, a University of Oklahoma student, says, “These students had relationships with other people of color…regardless of the ways that I think people are showing themselves on campus, there is a lot…going on behind the scenes that need to be investigated and pursued to find the truth in the ways that we deconstruct the ways that racism is perpetuating itself.”

Indeed.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Rachel Kuo is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a scholar and educator based in New York City. Her professional background is in designing curriculum and also communications strategy for social justice education initiatives. You can follow her on Twitter @rachelkuo.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more