Immigration reform has been a controversial topic for years. However, while politicians point angry fingers at each other – and at immigrants themselves – grade after grade of undocumented students continue to suffer.

These students have to hurdle arbitrary bureaucratic barriers, barriers that reproduce xenophobic hostilities and serve no purpose other than exclusion.

And the results are heartbreaking.

When other students assert that they will become writers, doctors, firefighters, artists, lawyers and teachers when they grow up, the dreams and aspirations of undocumented students are often squashed by systemic oppression and the gatekeepers whom enforce it. Consequently, these students are left to feel marginalized, afraid and pessimistic about their future.

It’s time that we, as educators, acknowledge and remedy the institutional and social obstacles in our schools and classrooms.

We must undermine the antagonistic narratives relating to immigration and make our schools more welcoming. If we don’t, we implicitly marginalize some of our most vulnerable students.

We have the opportunity to create a just world, not only for ourselves, but also for our students, who look up to us as guides and trailblazers in the fight against oppression.

1. Arbitrary Institutional Barriers

Undocumented students must jump through hoop after bureaucratic hoop in their pursuit of education.

K-12 Education

Students are guaranteed access to a public K-12 education, regardless of their immigration status. This, however, does not always mean there are not barriers that undocumented students and parents must overcome.

For example, registering for school requires a surprising amount of paperwork – including forms that repeatedly ask for things associated with citizenship (like social security numbers, birth certificates, and so on).

Thus, while citizenship is not required when signing a child up for school, having to fill out seemingly countless forms that ask for information that undocumented families do not have can be daunting and frustrating.

Proof of residence, for instance, is required to register at one’s local school. Proof of residence generally comes in the form of a signed lease and/or official mail (i.e. an electric bill) in the name of the parent that is registering the student.

However, immigrant families – especially those without documentation – often stay with established family members when they arrive in the country. In these cases, their family’s name is not attached to any bills or leases.

How, then, can they prove that they are official residents?

There are, of course, ways to establish residency in these situations, but it involves filing more paperwork at distant offices and then returning to the original school.

This process takes time, time that a student should spend learning instead of waiting.

Such a challenging and unwelcoming atmosphere often sets parents up to be suspicious of the school system from the outset.

Effective instruction requires trust and collaboration between teachers and parents. How, though, can we best teach our students if their families distrust us?

Furthermore, why do we even want to put parents and children into such a position in the first place?

Certainly, individual schools do not determine the registration process. But they often exacerbate a sense of unwelcome – and by unwelcome, we mean hostility, exclusion and prejudice! –towards immigrant families.

For instance, many of the aforementioned forms are only available in English unless specifically requested for another language. Further, many schools do not have translation services immediately available, nor are they required to have multilingual individuals on staff.

Schools might not be aware of the ramifications of monolingual resources, but they have a clear impact on students and families. How is a family to navigate a new system paved with paperwork in an unfamiliar language? How are they to feel about a system that demands English proficiency immediately?

Higher Education

The bureaucratic hurdles that undocumented students face become a full-blown obstacle course by the time they enter college.

There is no federal law that prevents US colleges from admitting undocumented students.

However, some states have placed restrictions on undocumented students attending public colleges and universities. Plus, most institutions of higher education set their own rules on admitting undocumented students.

Instead of easing the process for our most vulnerable students, this limits undocumented students’ access to higher education.

At the same time, undocumented students also have a more difficult time paying for college.

Even when they have lived in the US for years, many states force undocumented students to pay high out-of-state or international tuition cost – all while refusing them federal financial assistance. Further, not all states offer these students financial aid and there are few private scholarships available.

In fact, most states forbid undocumented individuals from taking out private student loans.

Disproportionately high tuition costs coupled with narrowed access to scholarships, grants and loans are even more devastating when we consider the challenges of employment for undocumented individuals.

Many undocumented students must work full time while going to school. As a result (like most low-income students), instead of studying, sleeping or networking with future colleagues or employers, they must work, often in fields unrelated to their career goals.

A lack of income also limits undocumented students’ access to required textbooks, a computer or other supplies.

And how do so many of us reward our undocumented students scraping together enough dollars to pay for tuition – all while foregoing sleep to read that extra chapter? We often chastise them for occasionally nodding off or arriving late. Or, we write them off as underperforming, unmotivated or unintelligent.

As opposed to being an empathetic ally.

We need to recognize the challenges that our undocumented students face every single day and brainstorm strategies to help them balance work and school.

We must also acknowledge that most undocumented students can only seek out the most affordable, local options, which frequently do not offer the same academic resources as pricier colleges or universities.

Many undocumented students also cannot access internships and other opportunities for professional development. And even for those that can, most internships are unpaid. This, therefore, makes them unattainable to the majority of low-income students.

What is the result of this bureaucratic obstacle course? Very few finishers.

Given such challenges, we wonder what jobs the anti-immigration folks feel these students are “stealing.”

2. A Culture of Fear

Undocumented individuals are often referred to as dangerous, criminal, lazy and un-American. Unsurprisingly, this prejudice makes many afraid of persecution and deportation.

Such fear creates a dangerous cycle that keeps undocumented students in the shadows. This makes them even more vulnerable and prevents many from pursuing the services that they can legally access.

K-12 Education

Undocumented immigrants tend to be fearful of being discovered as non-residents. Consequently, many undocumented parents are reluctant to register their children for school.

Those who register their children are our students’ parents and members of our communities. Why, though, do we do so little to ease their anxieties and assure them that there is no danger in signing up their child for school?

If a family is not ensured of the safety of the process, they could avoid registration altogether – the result of which would be a student not attending school at all.

We’ve seen it happen!

A child who has been in this country since infancy shows up to school at age 8 after the family has finally been assured the child can attend regardless of residency.

But the fear isn’t gone; it’s just taken a new form. Now it’s the child – arriving in time for third grade with no formal education to date – who’s afraid.

Sometimes, though, this fear is subtler. Wary parents register their children, but avoid signing additional forms like permission slips.

This means no after school sports or clubs.

This means no field trips!

And that’s a big deal. Because instead of enriching their education by visiting a museum or a zoo or a park, those students without permission slips have to stay back at school, alone and wondering why they’re being treated differently.

As teachers, we must address the distrust that so many of our undocumented students and their families feel.

If we don’t, our students may acquire the same fear as their parents. Then, instead of a place of acceptance and empowerment, school becomes a place of avoidance and defeat.

Higher Education

Anymore, the greatest obstacle to attending college is the price tag.

However, undocumented students who work to pay for tuition remain incredibly vulnerable to wage gauging and unsafe work environments. Afraid to either lose their job or to be deported, though, many do not complain when they encounter such illegalities.

Fear of disclosure can also prevent undocumented students from pursuing the college services they can legally access.

After years of being excluded from libraries, museums, hospitals and so on, many feel that their college’s resources are not for them. So, they don’t take advantage of college libraries or health care, counseling and accessibility centers.

Many undocumented students also fear not getting a job in their chosen field, regardless of how hard they work, their grades and earning a degree. Because without documentation, few immigrants are able to find professional employment.

Can you imagine how frustrating – or painful or desperate – this must feel?

And contrary to what most anti-immigration folks suggest, though, many undocumented students cannot just “go home” after graduation.

Because the US is home! That’s the only home they know. That’s where their family lives.

Furthermore, undocumented LGBTQIA+ students are frequently afraid of return. It’s often not an option for them if they want to live freely and safely.

These very legitimate fear worsens the marginalization of undocumented students.

It often exacerbates institutional barriers that documented students do not encounter. And it makes college more stressful.

How, then, can we expect these students to succeed?

Solutions

We must end the institutional and social barriers that make education more restrictive and inaccessible to undocumented students.

That means that we must promote broad, institutional change.

We need to change our state and federal laws to allow undocumented individuals unrestricted access to institutions of higher education, to provide them with funding and internship opportunities and to permit safe, professional employment.

And we need to do this now!

Some states have already removed some of the legal barriers that undocumented students face.

California now provides undocumented residents in-state tuition and opportunities to access state loans. And New York City’s new ID program offers all residents, documented and undocumented, access to libraries, museums and certain banks and credit unions.

However, these laws are far from nationwide. Nor do they sufficiently relieve all institutional obstacles.

And changing state and federal laws, while vital, will take a long time to accomplish.

What can we as K-12 and higher education instructors do now?

First, we can anticipate the anxieties and fears that most undocumented students and their parents feel by cultivating a safe, inclusive atmosphere in our schools.

This means welcoming all families.

This means informing undocumented students about—and actively encouraging them to take advantage of—all of the resources and services available.

This means being aware of how intimidating the registration process can be and deintensifying it. Teachers, administrators and staff should be able to calmly and confidently help undocumented students and parents navigate the complicated paperwork process. They should also enthusiastically accommodate linguistic and cultural diversity.

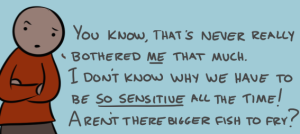

Second, we can use our teaching to dismantle dangerous social narratives relating to immigration.

For most of us, school was no picnic – it was hard! We struggled to get good grades. We struggled to make and keep friends. We struggled with self-esteem. We struggled to balance a part-time job. We struggled to find our true selves.

Now imagine adding to that list all of the struggles of being undocumented.

We must not avoid critical discussions of immigration because the topic is politically controversial. (If we did, what kind of social justice-minded teacher would that make us?)

By remaining silent, we implicitly support oppressive rhetoric and reproduce a harmful cycle of fear.

Instead, we should openly acknowledge that some of our own students and their families are undocumented. We should empower our undocumented students. And, we should encourage all of our students to critically challenge and rewrite the dangerous social narratives relating to immigration.

Of course, we must do this responsibly!

We absolutely should not reveal the identities of undocumented individuals. And we must anticipate the emotions – like fear, anger, sadness, and confusion – that all of our students might experience when discussing these issues in class.

Nonetheless, it is our responsibility as educators to cultivate a safe learning environment that promotes critical thinking and empathy.

***

Ask a Kindergarten student who they are, what defines them, and they will never answer “undocumented.” Ask them what they want to be and they will answer with enthusiasm and optimism.

Ask an undocumented college student, however, and many will articulate feeling trapped. Many express doubt and fear that their personal and professional dreams might not be realized.

We are not born with fear; we learn it.

So, let’s teach something else instead!

We must reform the institutional barriers that foreclose our undocumented students’ opportunities.

And we must teach all of our students not to be afraid.

We need to educate them about their rights, and reinforce the essential truth that all of our dreams and goals are of equal value. This is true for every student, regardless of their background.

Because, if we don’t teach these lessons, who will?

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Andrew Hernández is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is a public anthropologist and teacher and is completing his PhD in cultural anthropology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and he adjuncts at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY) and Baruch College (CUNY). You can follow him on Twitter @AndrewHernann or at his website www.AndrewHernann.com.

Jacquelyn Wagner is an English as a Secondary Language teacher. Having previously taught in the Bronx, she currently teaches at a public elementary school in a high-immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, NY.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more