Originally published on Murky Green Waters and republished here with the author’s permission.

Some friends and I have been talking lately about the ways that people with learning disabilities, developmental disabilities, and mental health issues have become excluded from the social justice organizations that we have been a part of.

Even in grassroots collectives and unions that strive to be inclusive and where people know how to talk about disability, many people don’t know concretely what steps to take to make their organizing more inclusive of us.

Here are some ideas to get you started.

First, a couple notes on terminology: I use the term disabled people rather than people with disabilities because that’s how I prefer to refer to myself, and a growing number of people are referring to themselves that way. Here’s a good explanation of why.

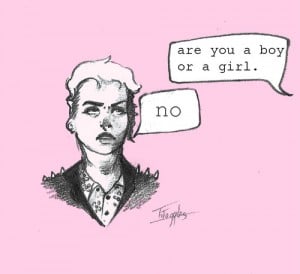

Neurodivergent is an umbrella term for people whose minds work differently than what is considered “normal” or socially acceptable. It often refers to people who have depression, anxiety, or developmental or learning disabilities, though it can include other things as well. It is the opposite of neurotypical, which just means someone whose brain works “normally.”

1. Don’t Expect Everyone to Do the Same Amount of Work

Too often, people’s legitimacy as activists is judged by how many hours of work they put into their activism. Remember that we all have different capacities.

Sometimes this is because we are required with to look after family members or work extra hours to pay the bills, but some of us need a lot of time just to take care of ourselves. Nobody should be excluded because of this reality.

Being open about boundaries is a good place to start; a group that has regular conversations about boundaries is more likely to respect them.

Active, enthusiastic consent is a good rule to live by and not just for sex: When you ask someone to step up to a task, it’s important to make sure you are not pressuring them into doing something that is beyond their capacity or comfort level.

Talking about boundaries means that people are more likely to say no to things in the short term, but it also means that they will be more sustainable as activists in the long term.

2. Accept People Who Are Flaky – And Find Ways to Include Them

Beyond respecting people who set boundaries, we need to respect people who back out of commitments at the last minute.

If someone calls and says “Sorry, I can’t make it today,” tell them that it is okay, ask what they need, and figure out who can fill in for them.

Of course this can end up being more work for the rest of the group and can be super frustrating, but it’s a good opportunity to have a conversation with the flaky person about how to rearrange responsibilities in the future.

Even better: Ask them what it was that made them have to back out, and (with their consent) try to find a way to stop the situation from happening again.

If your group doesn’t know how to deal with people backing out of commitments, it’s time to learn. For a movement to be sustainable, it should never rely too heavily on any one individual, and it’s better to assume that nobody can be expected at every single meeting and event.

If people are backing out of their commitments very frequently, it’s probably time to ask these questions: Are some individuals overcommitted? Or is the organization itself trying to do too many things at once?

If so, it’s time for a change.

3. Use Diverse Forms of Communication

People learn and communicate differently, and this isn’t an issue only for public schools.

People leading workshops and teach-ins should be aware of different learning styles and address them appropriately, and meetings should allow space for people who want to communicate visually or by writing things down.

4. Don’t Over-Pack Your Schedule

Anyone who has ever organized a weekend-long conference or meeting knows that it will always end with the organizers being exhausted. It seems to be inevitable.

I’d like to ask, when, exactly, did this become normal? The 9-to-5 schedule was invented by capitalism, keeps us dependent on it, and is certainly not healthy. It’s even harder to get through an eight-hour day if you have limited capacity.

Training days, conferences, and meetings should be planned to be a lot shorter than an eight hours a day and should have plenty of breaks.

Yes, you will cover fewer topics, but the ones that you do get through will be absorbed a lot better by participants because their minds (and yours) will be fresher and healthier.

Avoid having informal or extra meetings during break times.

Breaks are particularly important for people like me who live with anxiety, and holding informal meetings during break times means that some of us will be excluded from important conversations.

I was once at a student activist conference with a very heavy schedule where the organizers realized at the last minute that they needed to have something about disability in the program.

As a solution, they added a panel about disability during the lunch hour, when a lot of disabled people take necessary breaks. Having this panel over the lunch break left them with the difficult choice between participating in an important conversation about them or being a part of the rest of the day’s conference.

Breaks should be always be breaks.

5. Make Space for Emotion

This might seem obvious, but too many of us continue to ignore the assertions and ideas offered by those who express it while crying. The same goes with anxious responses (for example, hand-wringing) and angry voices.

Expressing emotions this way, as long as it isn’t harming others, is as legitimate as saying “I feel” or “I think” and should be taken seriously.

6. Make Community and ‘Getting Shit Done’ Separate Things

Activist burnout is a real thing.

Communities often form around social justice organizing, but when people have to bow out – for whatever reason – that shouldn’t mean losing their community, especially in a world where healthy community is scarce.

When people bow out, don’t assume that means they don’t want to be a part of social activities. Make sure that if someone stops showing up to meetings or decides to take a break from activism, the community is still offering them support and social contact.

7. Listen to Disabled People and Take Us Seriously

This is probably the most important point.

This isn’t an exhaustive list and neurodivergent folks are usually aware of how we are being excluded and will tell you how to improve, if you let us.

Remember that any disabled person you talk to knows a lot more about their disability than you do.

An acquaintance of mine was once told by another activist that her Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) was not a disability and that it actually makes a person more “productive.”

This is not a useful or acceptable attitude to have about other peoples’ disabilities or productivity levels. We get to decide how to define our disabilities, and what we need. Listen to us, ask what we need, and make it happen.

8. Remember That Having Us in Your Group Doesn’t Make You Special

I am not your token disabled friend, and the fact that you’re reading this doesn’t mean your group is going to be completely accessible.

Such a thing does not exist.

Keep learning and keep thinking about how people might be excluded.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Liz Kessler has been involved in organizing for student rights, disability justice, climate justice, and indigenous solidarity in Ottawa and in Vancouver over the last five years. She recently moved to Winnipeg, on Treaty One territory, where she is learning about gardening and prairie life. She blogs about neurodivergence at murkygreenwaters.com and you can follow her on Twitter @E_Kess.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32