How many of you remember Coca Cola’s “America the Beautiful” commercial that aired during the 2014 Super Bowl?

You know, the one where a bunch of bilingual Americans sang the hymn in their native languages, including English, Spanish, Hebrew, Wolof, French, Tagalog, and Keres?

Remember how everybody loved it?

I don’t either.

While many applauded the commercial’s message of inclusivity and acceptance, social media and conservative news outlets decried the multilingual rendition as ugly, insulting and contrary to the nation’s values.

The most common critique: “This is America, and in America, you speak English.”

Oppressive much?

Such a sentiment clearly privileges English speakers. But we should take an even closer look because not all English speakers are privileged equitably in the United States.

Expressing racist, classist, ableist and sexist prejudices, many people maintain negative presumptions against those who speak English with “un-American” accents, or with “urban” or “rural” accents. Many criticize or make fun of speech differences, vocal fry, the so-called “gay lisp,” and so on.

In other words, it’s not that all English is privileged. Instead, the USA tends to idealize Standard American English (SAE). SAE is essentially the neutral “non-accent” mostly associateded with the suburban Midwest.

Such SAE privilege — and conversely, the discrimination against non-English languages and non-SAE accents — manifests in many ways, though not for all of the reasons you might think.

Below are privileges that those who speak SAE have and a breakdown how SAE privilege harms non-SAE speakers.

1. You’re Assumed to be American

Let’s just get this out of the way: The USA has no official language! There is no federal law that states that citizens must speak English.

However, as evidenced by the negative backlash to the “America the Beautiful” commercial, many insist that to be American is to speak English.

This, of course, is a bizarre — not to mention oppressive — assertion because English doesn’t even come from the USA. It comes from England!

Prior to imperial English colonization, there were hundreds of indigenous languages in what became the United States. And many are still spoken.

And, following the US Invasion of Mexico in the mid-19th century, the USA annexed one third of Mexico’s territory. The Treaty of Guadalupe effectively converted the territory of millions of speakers of Spanish and various indigenous languages into American soil with the stroke of a pen.

There are over 300 languages that are spoken as a first language in the United States. And more than 60 million people in the USA speak a language other than English in the home.

Nonetheless, often only those who speak English (with American accents) are assumed to be American.

Consequently, those Americans who speak other languages are frequently told to “go back home.” They are often excluded from the spaces, institutions, and rights to which they are entitled.

2. Your Language Affords You Easy Access to Information

Go to the doctor’s office. Go to a school. Go to a restaurant. Go to a realtor. Go to a courthouse. Go on the Internet. In how many of those settings is English the only available spoken or written language?

How are non-English speakers supposed to navigate these spaces? How are they to gain equivalent access to education, healthcare and criminal justice?

Of course, legally, translation services are available in certain contexts — in public schools, hospitals, courthouses, police stations, and so on.

However, not everyone is aware that such services are available, or that when absent, they can legally request them.

Further, as a former courtroom Spanish-English interpreter, translation is an imperfect enterprise. Some words and phrases don’t translate that well. And many English speakers view the interpreter as burdensome and annoying.

I remember many interactions, for example, when the presiding judge refused to slow down when speaking so that I could adequately interpret what they were saying.

In other occasions, lawyers demanded that I speak so quietly that my client could barely hear me.

And the barriers to access don’t end there.

Most classrooms are English only. Schools are required to provide English as a Secondary Language (ESL) services, and some — the vast minority — offer bilingual or dual language classes.

Nevertheless, non-English speaking students often struggle academically and socially when placed in schools that demand English proficiency from the get go. Further, most standardized tests are available in English and only a limited number of other languages.

3. You’re Assumed to Be Intelligent, Educated, and Non-Violent

No language or accent is inherently superior to another!

Nevertheless, expressive of pervasive classism and racism, in the USA certain accents and languages are associated with intelligence whereas others are associated with violence.

I’ve noticed this based on my own multilingualism.

When speaking in English, people’s body language towards me is usually more welcoming. They smile more. They stand a little closer. They make few negative presumptions about my profession.

However, after talking to someone in Spanish, I sometimes notice a change in how nearby non-Spanish speakers orient themselves towards me. Sometimes their smiles disappear, and they take a step back. Or sometimes they ask certain classist and racist questions about my job or my “immigration status.”

The same could be said of other languages and non-SAE accents, particularly of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), for which there remain incredibly problematic and negative prejudices concerning its speakers’ supposed lack of education or gang affiliation.

This reflects a huge double standard, though:

Anglo native-English speakers who learn a second language are applauded for their intelligence and hard work. They’re told how many professional doors are going to open as a result of their bilingualism.

The same isn’t true for non-Anglo, non-native-English speakers who learn English as a second language. Rather than celebrating their intellect and perseverance, this kind of bilingualism is regularly treated as expected, and even the most minor mispronunciations and grammatical errors are criticized.

4. Your Accent Is Positively Represented on TV and in Film

On screen, how often does a CEO, a politician, a principal, a professor, a lawyer — any profession that we aggrandize in the USA — have a Spanish accent? an AAVE accent? a rural accent? an Arabic accent? a “Valley Girl” accent? a lisp?

Not too often.

Most “elite” characters have supposedly “safe” and “intelligent”-sounding SAE accents.

And when it comes to non-SAE accents?

Those roles go to some of our most harmful tropes: the dangerous undocumented immigrant; the undereducated, supposedly violent gang member; the unkempt “hillbilly” or “redneck”; the Islamic terrorist; the “ditsy” blond; the simpleton; or the overly feminine gay man.

Because non-SAE accents are narrowly and negatively portrayed in popular media, we are taught to think ill of the speakers of those accents.

5. Your Accent Is Not Satirized or Exaggerated

I’ve overheard many folks mock non-SAE languages and accents.

An acquaintance of mine pretended to mimic a coworker of Asian descent, saying, “Ching, chong. Ching, chong.”

On TV or just outside walking my dog, I’ve overheard groups of predominantly white people making fun of African American Vernacular English, appropriating phrases and pronunciations affiliated with urban Black culture.

Upon telling someone that my mother is an American Sign Language interpreter, they respond, “Oh, I know sign language!” and crudely sign the word “bullshit.”

When checking out at the grocery store, I’ve heard customers pretend to speak Spanish with the cashier with the Latinx last name by adding “o” to the end of each word.

But this is just a joke, right?

Wrong. Because “mock languages” are insulting, a type of covert racism that vulgarizes non-privileged languages and accents.

Mock languages also reveal a glaring double standard: While non-SAE speakers are expected to perfect their mastery of English grammar and pronunciation, the same is not expected of native English speakers learning, say, Spanish.

6. Your Accent Is Not Treated As ‘Exotic’

Hey, American English speakers, how many times have you gone out in the USA and been asked to “say something in American?”

Never happened, right?

Well, I remember a few years back when I was invited to a party. One of the other attendees was originally from Nairobi, Kenya. When some of the others learned this, they excitedly circled in and said, “Oh, say something in Kenyan.”

Clearly this partygoer was uncomfortable and reluctant to respond. But, ignoring her embarrassment, the group insisted. Finally, she sighed and, in Swahili, asked, “What do you want me to say?”

The group awed and laughed, commenting upon how “different” the language sounded.

And then they posed more ignorant and prejudicial questions: “How do you say ‘giraffe’ in Kenyan?” “How do you say ‘baboon?’” One also claimed to know the answer to these questions by citing The Lion King.

7. You’re Not ‘Misheard’ or Purposefully Ignored Because of Your Accent

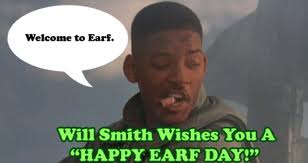

There was a meme going around a while back. It was Will Smith as Captain Hiller in Independence Day. In the film, just after knocking out the crash-landed alien, Smith very clearly says, “Welcome to Earth.”

The meme, however, transcribed the line differently:

Many assumed that Smith had pronounced the “th” sound as an “eff,” as is more common of AAVE accents.

Now, if he had said “earf,” that clearly would’ve been fine. Certain accents are not inherently better or worse than others.

However, when perceiving a non-SAE accent, many of us direct negative associations toward the speaker.

We also often stop listening, suggesting that it is the speaker’s responsibility to improve their accent and cater to our auditory prejudice and laziness.

Want more proof?

Years back, there was an experiment that compared comprehension and bias related to language.

Two groups of students took an exam, listened to a tape-recorded lecture and then took another exam. Investigators told Group A that the recording was an American, native-English speaking lecturer and told Group B that the recording was an Asian, non-native-English speaking lecturer.

But, they played the exact same recording — of a native English speaker — for both groups!

Comparing the scores and comments following the second exam, Group A scored significantly higher and responded more positively to the recording. Group B, however, scored lower and complained that they couldn’t understand the lecturer, that the lecturer needed to learn English and so on.

8. You’re Not Forced to Codeswitch

Ever notice how every national news broadcaster speaks the same?

No? Watch any episode of ESPN News and pay attention to when they turn the analysis over to the three sports — soccer, hockey and NASCAR — that ESPN has deemed more “regional?” Do you notice the switch to a Spanish, Canadian, or southern accent?

Unless purposefully trying to sound “folksy,” though — and it’s only folksy from an outsider’s perspective — most broadcasters train in SAE because (as described above) we are taught that speakers of this accent are safe and intelligent.

Of course, very few of us are national broadcast journalists.

But that doesn’t matter because the same privilege applies everywhere.

Because most people perceive my SAE accent as intelligent and non-violent, for instance, I’m not forced to change the way that I speak when at work, in the classroom, in court, and so on.

The same, though, does not apply to non-SAE speakers.

Now, I know what some of you might be thinking: “That’s not privilege. Everyone has to speak professionally when in the workplace.”

Well, let’s interrogate this. What does it mean to “speak professionally?”

Sure, it means that — unless I’m the boss, at least — I probably can’t swear while at work.

But it also means that a specific accent and specific phrases are expected, whereas other accents and phrases are deemed unacceptable.

This is not the same thing as saying that there can be no slang in the workplace, for example. Because certain informal sayings are definitely common in, say, an office.

“Make hay” means being productive in the short term. Getting your “ducks in a row” means being prepared and organized. To “boil the ocean” means wasting time. As most of these phrases — and there are many more — are associated with SAE, they privilege SAE speakers and those who can access SAE pronunciation and lingo.

Further, some common business jargon is just flat out racist (for instance, “Open the kimono” means to reveal information).

Those with non-SAE accents are forced to speak differently, otherwise they risk being labeled such racist, classist and sexist terms as “urban,” “country,” “girly,” and so on.

Subsequently, such perceptions negatively affect professional and academic advancement, criminal guilt and so on.

***

Speakers of Standard American English are formally and informally rewarded for their accents.

Alternatively, speakers of non-SAE accents and languages are often met with distain, negative perceptions and exclusion.

And, no, demanding that someone “just learn English” isn’t the solution.

Because this sentiment is an expression of SAE privilege, which itself is an extension of a system that privileges middle class, heterosexual, able-bodied, cis-gender, white men over everyone else.

Rather than insisting that non-SAE speakers change, therefore, we must stop perceiving non-SAE accents (and their speakers) in the negative.

We must celebrate linguistic diversity because such diversity highlights the vast diversity of experiences, knowledge and abilities that exist in the United States and everywhere else!

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Andrew Hernández is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is a public anthropologist and teacher and is completing his PhD in cultural anthropology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and he adjuncts at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY) and Baruch College (CUNY). You can follow him on Twitter @AndrewHernann or at his website www.AndrewHernann.com.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more