Originally published on xoJane and republished here with their permission.

I have never been a fan of yoga, yet I gave it a fighting chance, partly because I felt it was my cultural duty to do so.

Back in India, yoga is associated less with athleticism and more with spirituality and health. My grandmother was rendered almost entirely disabled due to a serious case of Parkinson’s, yet with the help of daily, soft yoga and regular meditation, she has begun to walk again with polished joints feeling as good as new. My grandfather, through repeated practice, claims to have come to clarity with his place under the gods and in the world, and at 80 years old still possesses the limbs and lungs of a much younger man.

My mother taught me a variety of yoga poses that, with patience, could function in lieu of medicine: stretches to alleviate menstrual pain, postures that helped with digestion, and repetitive chants to build memory and increase focus. Whether they held true or were kid-tested, mother-approved placebos to build will in us both, it was ultimately yoga. It was the collection of asanas and pranayamas that my people had crafted and curated and concocted to promote health, harmony, and spirituality.

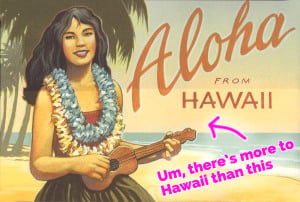

So you can see, when this cultural discipline turned into a billion-dollar industry featuring yoga pants and perky butts, a function for absolving the guilt-laden consumption of eating too many slices of pizza, or being an extracurricular duty of the suburban white mother, I was slightly perplexed.

Which is not to say that I have never gorged on ice cream with the promise of later engaging in power stretching in a room hot enough to shame Arizona summers. I have done yoga for tranquility as much as I’ve done it for a tight tummy.

Although when I attend those classes, I find yoga syncing closer with white girls with Starbucks than it does with an ancient Indian practice. It’s the women in those classes who go home and take #cultured selfies with Bindis and want to go to India to “find themselves.” And I, for one, have had it with selective cultural adoption.

I expressed this sentiment to my parents and to my surprise, they saw nothing wrong with people of other races cherry-picking parts of Indian culture. They lauded Jillian Michaels’ yoga series, embraced Selena Gomez’s and Iggy Azalea’s respective interweaving of Indian culture with western music, and admired Kendall Jenner for adorning a bindi at Coachella.

To them, it was a sign of their culture gaining mainstream acceptance. To me, it was thievery and a selfish promotion tactic.

What shift in mindset occurred in the span of one generation that placed me on a starkly different side of the spectrum from my parents?

My parents emigrated from India to America in 1991, and had me two years later. I was born one culture, yet born in another one. From as long as I can remember, I have constantly been reminded of my other-ness. I was bullied so much for my school lunches that I often boycotted eating all together.

Kids reduced me to my country’s worst stereotype – being eternally stinky from eating curry – and mercilessly mocked me for putting coconut oil in my hair, a typical home practice in India to maintain our thick hair.

I remember an Indian girl in my fourth grade class who hung out with the popular girls because she had the luxury of residing right next door to our grade’s queen bee. She quietly parted from her friends and came up to me while I was crying in the library.

With a deceptive cool masking the inkling of solidarity in her tone, she told me: “Don’t worry. My mom puts oil on my hair too. Just make sure you do it during the weekend and wash it off before you come to school.”

Looking back at that now, I realized us first-generation kids spend our most formative years trying to fit into a culture that demands assimilation while simultaneously barring us from it.

Fast forward to my twenties and I can see the slightest hints of cultural shame still lingering within many of my friends. My Indian friends get visibly embarrassed when their music playlist “accidentally” shuffles to Hindi music, music which they all colloquially refer to as a “guilty pleasure.”

They put time and sweat into practicing traditional dance styles like bharatnatyam and raas and garba but when asked to describe their activities to non-Indians, will just call it their “dance team.”

We have all grown to accept and love our brownness, yet the relentless battle for assimilation has left so many bruises that instinctively provoke knee-jerk responses to ensure distance from our Otherness. We spent our whole lives trying to love our parents’ culture and accepting ourselves as the curry-eating, oil-scrubbing, naturally-tanned selves we are, but we never really did. And we thought nobody else really would either – even those who share our background.

For those of us who grew up in a Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Bangladeshi, or Nepali household, our struggles to fit in are vastly different in magnitude, but the solidarity exists.

So that’s why we are upset when someone wakes up one day and decides to exploit our turbulent identities as a disposable fashion – and by doing so be rewarded as a paragon of globalization and cultural acceptance.

How dare they regard Indian fashion as effortlessly cool and chic while we make it look “fobby,” or a stubborn adherence to our culture that purports us to be “fresh off the boat?”

How dare they have a crush when we spent our entire lives trying to love?

Our parents, on the other hand, never came to this country for assimilation; they came here for survival. They knew from the onset they weren’t going to be accepted. They grew up embedded in a deep sense of cultural identity – one that everyone around them shared. They always knew where they are from and they owned it, even when they arrived in America.

Our parents grew up in a time where white people were inherently superior, and while it was commonplace for Indians to ditch their traditional clothing for jeans and t-shirts, white people were reluctant to do the same for them.

Years later, our parents’ generation is bursting with pride at the thought of all the customs they accepted being embraced by the mainstream – whether it’s being exoticized or not. Our parents see the western infatuation with select parts of their otherwise deeply rich culture less as self-promotion and more as an acknowledgement; it is a cross-cultural equalization they could have never dreamed of.

My generation of Indian-Americans is not really Indian, and not really American. Our endless journey to fit into the western mainstream while trying to retain our roots left us – and continues to leave us – in an eternal purgatory of identities.

Americans getting to be fully American and a little bit of Indian – whenever they please – isn’t fair.

Yet I know it isn’t right to outright ban non-Indians wearing Indian clothes because the intentions are never malicious – plus I know my parents are happy to see them.

But the beauty of culture lies in every single part of its intricate details, and hand-picking a favorite few while discarding the rest is taking for granted the best parts of that culture. At the end of the day, your bindi selfies will eventually disappear on social media’s news feeds, you’ll take your colorful sari off, and you can go back to being American whenever you want.

But for my generation, we can never go home and remove our heritage, our culture, and our riddled identity struggle.

Our parents definitely had their struggles, but they never compromised their cultural integrity. They proudly donned their saris and kurtas, brought their food in curry-stained tupperware to work without a care of what anyone else will think. They knew they were outsiders and were never trying to fit in in the first place.

To them, selective adoption of Indian customs and fashion is a compliment, a recognition, and not a double standard of acceptance. And that’s why they’ll continue bask in the appreciation we deem appropriation.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Nikita Redkar is a freelance writer in New York City who currently interns for Fusion Network where she writes about diversity in pop culture and how it’s shifting the current landscape of racial and gender politics. When she’s not writing, she is taking classes in sketch comedy and reading bizarre astronomy theories. She likes cute animal gifs and dislikes long walks on the beach, plagues, and other cliches.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more