I have experienced a lot of street harassment in my life.

And as a white, cisgender, able-bodied woman with thin privilege who, for the last five years, has been partnered with a cisgender man, I experience a very particular kind of harassment.

“Hey, baby. You’re sexy. Can I get your number?”

Sometimes it’s about the leg hair that I choose not to shave.

“You look like a man with those hairy legs! You should shave those.”

I’ve grown accustomed to being subjected to sexual harassment and violence every time I leave my house, but each time it happens, I still feel the same way – dirty, violated, ashamed, embarrassed.

And while I’ve grown accustomed to regularly experiencing sexual harassment when I’m out and about, I thought it would stop when I had a kid. I was sure that people wouldn’t harass a mother and her baby. I was wrong.

When my child was a few months old, I sat on the train, nursing my hungry baby. It was then that I heard it.

“Ugh, can you believe she’s doing that here? I don’t need to see her tit all out like that!”

A familiar feeling came over me and I could feel the redness creeping up my neck – dirty, violated, ashamed, embarrassed. Even though the context was different, the motivation and result of what I experienced was exactly the same.

Street harassment is harassment and violence that occurs in public spaces. Public space can be both physical and digital, and this harassment can range from unsolicited commentary and catcalls to leering, stalking, groping, and other, more severe forms of violence.

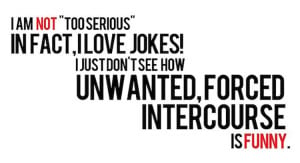

What all these incidents have in common is that the person they are directed at experiences them as unwanted or intrusive. This makes street harassment subjective; each person has the right to define their own harassment and everyone’s experience of harassment different.

Every individual’s experience of harassment is also valid.

So while I might consider it harassment to be stopped by a man so he can tell me that he likes my hair, you might not. But that doesn’t mean that either of us is wrong; we’re both right.

Every person is allowed to define street harassment for themselves. If they experience something as unwanted or intrusive, then it is. Period.

Street harassment can be sexist, racist, homophobic, transphobic, ableist, classist, or based on any other marginalized identity that someone holds. The kinds of harassment that people experience will be based on the intersections of identities that they carry with them into the world.

This means that some of the harassment I experience will look very different than the harassment a trans woman of color faces, or that a queer man faces, or that a fat woman faces.

So what does this all have to do with breastfeeding?

Harassment of parents who nurse in public is a form of sexual violence, like street harassment. Further, people who breastfeed children experience other forms of marginalization and street harassment – that have nothing to do with their breastfeeding status – due to the fact that they are cisgender women, trans, gender non-conforming, and/or intersex.

Therefore, when nursing parents enter public space, our status as nursing parents gives us one more identity that we can receive harassment about.

Here are 8 things that harassment of parents who nurse in public have in common with street harassment.

1. It Treats Bodies Like Objects By Fixating On Their Parts (Like, You Know, Breasts)

Street harassment is a form of objectification.

When a woman is walking down the street and someone yells “Nice rack!” or someone is waiting in line for coffee and the person behind them is staring at their ass the whole time, that’s objectification.

Objectification means reducing someone to their body parts, or treating them like an object instead of a person.

When nursing parents are harassed in public space, we are also being objectified. We are being reduced to our breasts, instead of being viewed as a whole person who just happens to be feeding our child.

Or if someone is fixated on the fact that we are feeding our child, we’re being seen as simply a food source and not a whole person. This is objectifying, too.

Objectification is harmful because, in dehumanizing marginalized people by seeing us as objects, it creates a culture in which violence against us is acceptable or not taken seriously.

A key component of street harassment is the element of objectification, and this is exactly what happens when a breastfeeding parent faces harassment for nursing in public.

2. It Seeks to Control What Space Marginalized People Occupy

Street harassment seeks to send the message that marginalized people are not allowed in public space by making those of us who experience harassment feel ashamed or threatened.

When a parent experiences harassment for nursing in public, they’re receiving those same messages.

They’re being sent the message that they cannot be seen in public when they are doing what they’re doing – which, in this case, is nursing their kid.

They may be embarrassed and feel like they have to cover themselves. They may feel like they have to go sit alone in their car or in a bathroom stall to nurse where no one can see them. They may even avoid going out in public due to fear of receiving comments for nursing.

For me, this happened when I posted a photo to Facebook of myself nursing my child. The photo was reported for nudity, despite the fact that Facebook’s terms of service allow breastfeeding photos.

The person that reported my photo was telling me that I could not take up space on social media if I was going to be visibly breastfeeding in that space. They were seeking to stop me from accessing that space with my nursing photo.

This also happens in physical spaces when nursing parents are asked to leave restaurants or other establishments for nursing. Like Facebook’s terms of service, the law protects mothers who are nursing in public (unfortunately the laws are cissexist and don’t currently “protect” nursing parents who aren’t cisgender women), but that doesn’t stop other people from telling them they can’t.

When someone becomes uncomfortable enough to leave a public space, the space they occupy has been dictated by the harassment they’ve experienced.

3. It Demonstrates a Sense of Entitlement to Comment On, Touch, or Ogle

This is the crux of what allows street harassment to happen: People from dominant groups feel entitled to the bodies of marginalized people when they’re in public space.

Sometimes that looks like a police officers targeting, stopping, and frisking a group of young men of color simply because they were walking down the street.

Sometimes it looks like a heterosexual couple yelling a homophobic slur at a gay couple who is out to dinner together.

Other times, it might look like a cisgender woman purposely misgendering a trans woman on the subway.

And sometimes it looks like a parent who is nursing their child in the park being told by a passerby, “Ew, you should cover up!”

In this instance, caught on video, the nursing mother is actually spit on and called “a slut” by a man after the woman he is with berates her for being “nasty” while she nurses her child on a park bench.

For a trans or gender non-conforming parent who is breastfeeding publicly, this harassment may be compounded by intrusive comments or questions about the parent’s gender.

What all of these interactions have in common is that someone felt entitled to comment on, touch, or intrude upon the body of a marginalized person who was occupying a public space.

4. It Ties into a Larger Culture of Blaming Victims When They’re Targets of Sexual Violence

When the story about my nursing photos being reported went viral, one of the most common comments I received from strangers was, “If you post pictures like that on the Internet, what do you expect is going to happen?”

What they meant by these comments was: “If you post pictures of yourself breastfeeding your child, you should expect to be harassed and reported for it.”

This kind of thinking is what’s known as victim-blaming, along the lines of the logic of, “If you go out in a short dress, you’re asking to be catcalled or harassed.”

When people are harassed for nursing in public, often they hear things like, “Well, you should have used a cover.”

“This wouldn’t have happened if you just used bottles when you’re out.”

“Why didn’t you just go feed the baby in the bathroom?”

Sound familiar?

“If only she hadn’t gone back to his room with him, this wouldn’t have happened.”

“Maybe if you hadn’t had so much to drink…”

The logic of blaming victims of nursing-in-public harassment and victims of sexual violence is exactly the same.

Victim-blaming is perpetuated by a patriarchal society, and that means that it’s not just men who are exposed to these views – other marginalized people, including women, also internalize these messages.

Many of the victim-blaming comments that I received were not from men, but from other cisgender women.

When we engage in victim-blaming behavior, our blame is misguided. Instead of putting the onus on the nursing parent to cover up, leave, or feed their child differently, we should instead be looking at the people who are bothered by the behavior – and telling them to get over it.

5. It Views Marginalized Bodies in Relation to the Male Gaze

In our patriarchal society, the male gaze is the default. It is the lens through which dominant culture – white, male, heterosexual – views the world.

The male gaze assumes that whatever a woman is doing with her body is being done for the benefit of the gazer – in this case, heterosexual men.

In the case of a woman being catcalled when walking down the street, it’s assumed that the dress she’s wearing must be because she wants to entice men.

In the case of a mother breastfeeding publicly, it’s assumed that she shouldn’t be doing it because it’s going to distract or entice the men around her, because that’s what breasts are for – enticing men.

Because of course breasts are strictly for enticing men and definitely not for feeding children.

But this is why, often, comments aimed at women nursing in public take the tone of, “You need to cover up because my husband/son can’t stop staring at you!” Our culture views women’s breasts as existing solely as sexualized body parts because of the male gaze.

What the gaze also assumes is that anything being done with a female body that is not for the benefit of the gazer is wrong or invalid.

That might mean a transmasculine person’s gender presentation is policed because they’re not presenting in a stereotypically feminine way.

It also might mean that someone using their breasts to feed their child and not for the benefit of an interested male is told to “put it away.”

But our bodies exist outside of the male gaze and, when I’m breastfeeding, that’s all I’m doing.

I’m feeding my child, not the male gaze, in the same way that I dye my hair bright colors because I like it and IDGAF whether or not random men approve.

6. It Polices Behavior By Making Certain Behaviors ‘Worthy’ of Harassment

Street harassment sends the message to the people who experience it what is socially acceptable for us to do with our bodies. Harassment reminds us when we step out of our socially prescribed roles.

That might look like a gender non-conforming person being harassed for not having a gender identity that is easily placed along the binary.

It could look like a queer couple being harassed for holding hands with someone of the same sex.

It might look like a cisgender woman being told that her dress is too tight and that she “looks like a slut.”

Or it could look like a person who is nursing their child being told to cover up.

In all of these examples, the actions that a marginalized person is taking with their body is being policed by a stranger when they are in a public place.

This policing is an attempt to force people who stray from their socially accepted roles into the one that society thinks they belong in.

However, everyone is entitled to do what they want with their body because they have bodily autonomy and that’s how that works.

7. It Dictates Which Activities Are Acceptable for Marginalized People to Engage In

Street harassment attempts to make clear what behaviors are not acceptable for marginalized people by harassing us when we engage in them.

These behaviors include walking alone, walking in groups, walking at night, walking during the day, wearing a dress, wearing sweatpants, having brown hair, having purple hair, having leg hair, taking the train, being too feminine, being too masculine, being Black, being Latinx, being East Asian, being South Asian, being fat, being thin, being disabled, using a wheelchair, using any kind of mobility device, running, cycling, going to the gym, dancing in a club, waiting in line for coffee…

…and nursing.

Essentially, all of this harassment attempts to tell marginalized folks that we don’t belong in public space at all. And while our bodies do not become public space just because we step into public space, it very often feels like they do.

8. It Makes People Who Experience It Anxious, Afraid, or Ashamed

People who experience street harassment report some pretty intense effects. Street harassment can result in feelings of anxiety and hyperarousal in public places. So, too, can harassment (or even the fear of harassment) when someone is nursing in public.

Even as someone who feels well within my rights to breastfeed my kid in public, I’m always scanning the room in anticipation of being confronted by someone.

Similarly, I find that I’m constantly on edge when out and about by myself, worried that a man is going to come up and start bothering me.

Street harassment can also cause those of us who experience it to avoid certain places, or to feel shame or self-blame after we’re harassed. We may question why we were walking in a certain location or why we wearing a particular outfit, looking for ways to blame ourselves for our harassment.

People who are harassed for nursing in public experience similar things. They may stop going out in public, and, in some cases, it may even cut a parent’s nursing relationship with their child short, as nursing in public becomes too challenging for them and they can’t keep their supply up.

Or they may engage in self-blame for the harassment, thinking that they should have used a cover or gone out to their car to avoid being seen.

All of these consequences are a big deal – they have a damaging effect on the people experiencing them and affect people’s mental health, emotional well-being, and physical safety.

***

Ultimately, street harassment and the rights of nursing parents are often seen as two distinct issues. However, they’re very much related. But when our activism happens in silos, it makes progress harder to come by.

Anti-street harassment activism can and should include the rights of nursing parents. If you’re doing anti-street harassment work and you’re not actively advocating for the rights of parents to nurse in public, then your work is incomplete.

Until we recognize harassment of parents who are nursing in public as the sexual violence that it is, we’ll be unable to do what’s needed to stop it.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Britni de la Cretaz is a Feature Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a feminist momma, community organizer, freelance writer, and recovered alcoholic living in Boston. She’s a founding member of Safe Hub Collective. Follow her on Twitter at @britnidlc. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more