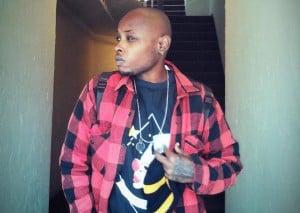

Activists protest in Times Square in response to the recent fatal shootings of two black men by police

When Black people get killed, the world stops for other Black people – because it could have been them that day. But for many non-Black people, it’s business as usual.

The media has been strategic at desensitizing Black deaths by continuously showing us images of massacred Black bodies. By exposing murdered Black bodies over and over again, the public no longer sees it as “new” news.

Being a Black, queer, and mentally ill immigrant in the United States means that I wear my skin, my afro, my nose, my PTSD, my mood swings, my height, and my accent tight around my neck. If at any moment, I’m not careful, I can be shot dead.

And I’m not exaggerating. This is the truth that I live.

Just this January, the state police in East Boston, Massachusetts, stopped my family in a tunnel. Before asking my stepfather, who was the driver, for his license and registration, the state police officer looked inside the car to see who the passengers were.

The White officer spotted my eleven-year-old-brother and ten-year-old-sister and told them, “You’re going to be criminals like the rest of your kind.”

Make no mistake: This was a racist interaction. And it caused my brother to have an intense anxiety attack that night that brought many tears – as well as many questions.

My brother is a mixed-race child of immigrants. My brother is dark skinned – much darker than I am – but racially ambiguous. See, he’s the child of an Afro-Indigenous womyn from Mexico, and a pan-indigenous man from Guatemala. But at just eleven years old, my brother has had to face what it’s like to be Black and dark in America.

Just this January, I realized that I would have to do better in supporting my brother, because although we are both Black, he lives a different experience as someone who has a lot more melanin than I do.

See, being Black in the United States means being told when you’re in grade school that you should never walk too fast on the street, or too slow, no matter how long or short your legs are. It also means that you might automatically be labeled as a threat or a criminal in the same way that the racist, anti-Black state police officer labeled my eleven-year-old brother.

Not only do I need to do better as a Black person to support my brother, but also, those who are not Black need to commit themselves to change culture.

This piece is for you, my non-Black friends, my non-Black family members, my non-Black activists, my non-Black educators, and my non-Black partner. This piece is for you, because whether you know it or not, you benefit from anti-Blackness.

Even if you’re a non-racist activist, it doesn’t mean that you escape from the benefits of anti-Blackness. Anti-Blackness means that someone that looks like me is more likely to be perceived as dangerous than someone who looks like you, my non-Black counterpart. This is a US reality that you unintentionally benefit from.

It’s not your fault that Black people are systemically seen as inhuman, but you can be part of our oppression if you don’t name anti-Blackness when you notice it – or if you’re unable to have conversations with non-Black people about anti-Blackness.

I need to mourn. I need to be there for my family in these violent times. But I also need you.

I need you to commit to stand by our side, and to not make this about you. I need you to acknowledge that being Black in the US is an experience like no other.

And if you really believe in solidarity and allyship, here are ten things you can do right now to support us.

1. Don’t Demand We Share Our Thoughts On Every Black Murder

When a tragedy happens in the Black community, I usually talk about it with my close friends and family.

But it’s gotten to the point that I share so much of my analysis on Facebook, that when I don’t jump on a national conversation after a tragedy, I get private messages from non-Black people, demanding that I tell them what I’m thinking.

Non-Black people shouldn’t demand a Black person to develop an analysis on another police sanctioned murder of a Black individual – even when you think you’re asking nicely, even when you’re asking because you want to help.

We, Black people, already have an analysis because we live this on a day-to-day basis. And we don’t need to share it with you.

Instead, what non-Black people should do is attempt to battle with the ways in which they’ve historically benefitted from the oppression of Black people in the US – and publicly name those forms of benefits, as well as how they continue to oppress Black people.

I understand that non-Black people want to ask Black folk what they’re thinking so that they can be better allies. I get it.

But think about it this way: If you go to a funeral, you’re not going to demand that the family re-tell you how the person died, because that’s a lot of psychological and emotional space you just demanded for yourself, instead of carving out space in your life to hold the family who is mourning.

2. Read Articles Before Sharing Them on Social Media

This mistake – not reading before sharing – I’ve unintentionally committed, and it’s had serious consequences.

A few years ago, I shared an article about the murder of a trans womyn. The headline was something along the lines of “X Trans Person Killed This Year.” The article, however, would at times refer to the trans womyn by “she” and at other times by “he.”

By not reading the article, I participated in continuing to perpetuate violence against a transgender womyn who had been killed by the police.

We need to be critical and careful when sharing online information.

Not only do we need to hold writers and artists accountable, but also ourselves.

I see many people in my community share article after article without any context of why they’re sharing it. Maybe the title spoke out to them – or the excerpt that went along with it. Maybe they trusted the person that they shared it from, and so assumed that it aligned with their own values, too.

But perhaps take a second and see if the information is accurate, if it truly speaks to your soul and your cause – or if it’s actually, in some way, further hurting the people you’re advocating for.

3. Don’t Share Content Created by White People Narrating Black Experiences

Think about your own marginalized identities. And imagine someone – who doesn’t share this personal experience – talking from your perspective.

How would you feel?

I’d feel angry. In fact, I feel angry right now.

These past couple of days, I’ve noticed that people on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have been sharing photos of White folks along with their analysis on #BlackLivesMatter – posts that, imbued with Whiteness, have gone viral.

You know why this has angered me? Because what these people are saying is not new. In fact, Black people – and particularly Black womyn – have been saying the same things for decades. But their knowledge is taken for granted because not only are they Black, but because they are also womyn.

We need to re-evaluate who we uplift – and at the cost of whom.

You want to share posts that speak truth to power? By all means, do. But make sure that those posts are coming directly from the community affected.

4. Uplift the Voices of Dark, Fat, Queer, Trans, and Disabled Black People

In order to be accountable and uplift voices, what we need to do is see all Black people as knowledge producers and intellectuals – that they are the experts on their experiences, what they need, and how we can address their needs.

Patricia Hill Collins, in her phenomenal book Black Feminist Thought explains that “Black women intellectuals can stimulate a new consciousness that utilizes Black women’s everyday, taken-for-granted knowledge. Rather than raising consciousness, Black feminist thought affirms and rearticulates a consciousness that already exists.”

Think about who are the most marginalized people in any given movement. And make a conscious effort to amplify their

By uplifting the voices of dark, fat, queer, trans, and disabled Black folks, we provide an understanding of the ways in which we can work together to change culture – and depart from living under a slave/master political regime.

5. Offer Food and/or Safe Housing to Black Folk

As people engaged in social justice work, I really do believe that we often fail at addressing the basics: food and shelter.

Perhaps, a better strategy to be an ally and in solidarity with Black folk in the midst of violence is to offer them food or a place to sleep.

This is needed because when we’re hurting, we sometimes forget to eat. And to be honest, food is sometimes inaccessible to people in my community. I definitely have spent my fair share of days of hunger.

Shelter is also important. Due to problems like gentrification, poverty, and racism, many Black folk live in unhealthy places. A home may be unhealthy because one of our roommates might be racist or because it’s regulated by police circulation, thus putting our bodies at fight or flight mode all the time.

Some of us may not even have a place to call home.

Just say, “Hey, would you want to spend the night at my place? You can take the bed, and I’ll take the couch, or we can share my bed.”

6. Buy Grocery Store Gift Cards and Distribute Them to Homeless Folk

Again, hunger is real. But also, did you know that non-Black homeless people are more likely to receive better treatment than Black homeless people?

The harsh reality is that homelessness has nothing to do with a person being inefficient. The reality is that homelessness is an issue created by a society that doesn’t prioritize community health.

We live in a society that doesn’t combat racism, sexism, and classism in the K-12 education system or in the workforce – in a society where Black folks never received reparations. What can you do to help that?

Last year, I wrote an article about what it was like to be an undocumented activist, and in it, I named the fact that I was often hungry, and how far I would go with $15 in grocery gift cards.

This isn’t something I’m making up. This is a real lived experience, and a real need in my community that will help us mourn.

7. Offer Childcare to Folks with Children

When tragedies happen, our lives stop. But somehow, we have to keep going – because everything around us doesn’t stop.

For those Black folks with children, mourning, breathing, and decompressing may become harder, and at times, impossible.

If you know Black folk who are parents or guardians of children, offer childcare.

Childcare might look like your visiting their home and playing with the child(ren) while a parent or guardian has coffee in their kitchen, or it may look like your babysitting while a parent goes to a protest – because for the Black body in America, protesting is often the way we mourn.

8. Redirect Conversations Between Non-Black People and Black People to Yourself

If you see a non-Black person attacking, or demanding a Black person to defend why #BlackLivesMatter is important, you should direct that conversation to yourself.

A good way to be an ally is to engage in conversation with other non-Black folk about what’s going on – and to break things down for them.

For Black folks to do this work is for Black folks to literally have to prove their humanity over and over again, which is something that’s disempowering, violent, and traumatic.

9. Create Spaces for Non-Black Folk to Make Community Commitments

It’s really important for non-Black people to get together and find ways in which they can collectively fight against anti-Blackness and racism.

For example, if you live in a neighborhood where police circulation is frequent, you might want to call a meeting with non-Black neighbors and commit to no longer call the police. This may look like creating a system of first respondents. For example, if you’re bothered by music, instead of calling the police, you have another system in place to deal with things like this.

Another great example is for you to host a community forum of what White Privilege, Anti-Blackness, Patriarchy, and other oppressions are – and how to address them in the everyday life.

These are the ways in which you, as a non-Black person, can do the work that is needed to shift culture.

10. Donate Money

So, this is the last one, because I need y’all to take some real good notes.

Donating money doesn’t always mean giving hundreds of dollars to an organization. Donating money has to go further. You need to invest no only in organizations, but in people.

Daily, my newsfeed on Facebook is filled with GoFundMe campaigns of fellow Undocumented and Black immigrants asking for financial help, trans and queer Black folk who are escaping violent situations, and Black folk in need of medical help.

I want you to commit to no longer ignore these causes. I want you to make a commitment to donate when you can. If you can’t, because that’s also real, I ask you to send it to ten people and ask them to give.

Because this is how we can fund our communities.

***

If you can commit to following the points in this guide, and to share and re-share this guide, you will be contributing to changing a culture that is indebted in the oppression of Black individuals.

Think of my brother, who at eleven was labeled “criminal.”

Is this the culture you wish to be a part of? If it’s not, you can do something about it, and you can start today, because my brother is not the first child to go through such psychological abuse by the police.

My ask is for you to commit to fight for the liberation of Black people. Because if one person in the community is oppressed, we’re all oppressed – which means that someone is benefiting from our oppression, and that might just be you.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Alan Pelaez Lopez is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and an Afro-Indigenous migrant that grew up in Boston via La Ciudad de México, documenting their existence as an (un)docuqueer poet, jewelry designer, and a huge Frida Kahlo fan. Alan is currently in graduate school pursuing a degree in Comparative Ethnic Studies in the Bay Area, and a member of Familia: Trans, Queer Liberation Movement.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more