(Content warning: sexual violence, sexual assault, trauma)

When I found out I was pregnant, my first reaction was sheer elation. We’d only been trying to conceive for a few weeks, and I was thrilled that it had happened so quickly.

That joy was quickly replaced by a sinking feeling of terror.

I’m a survivor of sexual violence – many times over. As a result of these experiences, I have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

That means that for me, living in my body can be really difficult at times.

Sometimes I have panic attacks about things that don’t really seem like a big deal, or sometimes they’re more obvious, like when I’m trying to be intimate with my partner.

Sometimes I’m really spacey and out of it and it’s hard for me to stay present.

Sometimes I dissociate, which means I kind of leave my body and go somewhere else. That’s most likely to happen when I’m trying to get physical with my boo.

I’ve done a lot of work to try to make my body feel more like mine. I’ve gone to therapy, done yoga, and even sat for a boudoir shoot!

So the thought of suddenly having to share that body with another person was really scary, because I didn’t know what it would be like. After having done so much work to make my body feel like it belonged to me, I couldn’t imagine having to give it over to someone else.

Sexual violence is a very common experience for marginalized people, so the chances that a pregnant person is also a trauma survivor are high.

And if that’s the case, why aren’t we talking about it more often? Why aren’t providers having these conversations with pregnant people who come into their office?

The way that sexual trauma can affect survivors when they become pregnant might be different from how their trauma affects that person on a day-to-day basis, and it may also be different from how non-survivors experience pregnancy.

And while midwives are much better at discussing these issues, the medical community at large never really addresses it. Nor do we hear it talked about much in birthing classes, breastfeeding groups, or anywhere else that new parents are going for support.

But, as feminists, we know that no one leads a single-issue life (thanks, Audre Lorde). So sometimes, people who are trauma survivors need to navigate a pregnancy, and they may find themselves wholly unprepared to do so.

So, to start us thinking about this, here are some of the ways that sexual trauma can affect a pregnant person.

1. They May Not Be Excited About Their Pregnancy

Even though my pregnancy was planned and wanted, I felt totally indifferent about it for the first several months.

Feelings of detachment and numbness are very characteristic of my PTSD, and so sometimes it’s hard for me to be excited about things.

Everyone else in my life was ecstatic, and I was just… meh. And I felt a lot of shame about the fact that I wasn’t feeling what I should be feeling.

I put more pressure on myself to try to manufacture the kind of reaction that I thought I was supposed to have, which added to my feelings of guilt.

If the pregnancy is unplanned or the result of an assault itself, this can further complicate feelings about it.

And while women are not the only people who get pregnant, there is a unique expectation about how women in particular should feel about being pregnant.

Women are told by society from the time they are little girls that the thing that will be the most fulfilling for them in their entire life will be to have a baby. We’re told that becoming a mother will complete us.

At the most extreme and conservative end of that conversation, we’re told that our purpose in life is to bear children.

But despite the dominant narrative that pregnancy is nothing but a time of joy and excitement, it’s more complicated that that, particularly for those of us who have survived sexual violence in our lives.

Sometimes it’s joyful, sometimes it’s scary, sometimes it’s awful, and sometimes it’s all of those things mixed together.

All reactions and feelings about pregnancy are valid, and there is no right or wrong way to react.

2. They May Worry About Losing Control Over Their Body

For many survivors of sexual violence, that trauma involved having our power and control over our bodies taken from us.

Regardless of who the perpetrator was – a partner, a friend, a stranger, a relative, a medical provider – and regardless of how old we were at the time – child, teenager, adult – sexual violence is characterized by having control of our body stripped from us in that moment (and sometimes repeatedly).

During pregnancy, things happen to your body that are completely out of your control, whether it’s your expanding belly, the weird bodily functions, or the baby’s movements in utero.

For many survivors of sexual trauma, we may associate a lack of control with the abuse or violence that we’ve suffered.

Relatedly, feeling or being in control may be a way that we cope with the aftermath of our trauma, and may be necessary for us to feel safe.

For me, that looks like planning all our family’s trips and always knowing what food we have in the house and what meal it’s planned for. I don’t like places that put me out of my comfort zone or where I have no escape from feelings of discomfort.

I was so terrified of losing control of my body during pregnancy that, for a long time, I told myself that I didn’t want kids at all, because the thought of having to give my body to another human filled me with panic.

And this fear contributed to…

3. They May Experience Dissociation from Their Body

Loss of control over my body meant I often felt disconnected from it; there was some degree of dissociation that I participated in. It’s my brain’s way of coping.

My PTSD symptoms are characterized by numbness and dissociation – that numbness is both physical, in that I have very little sensation in my pelvic region, and emotional, in that I often feel nothing at all about things that should make me happy or sad or angry or scared.

For other people, their PTSD symptoms look different. They may have frequent panic attacks, flashbacks, nightmares, or hyperarousal. I have these, but rarely. I’m much more likely to be numb, distant, and spacey.

And so what happened during my pregnancy is that it felt like this thing that was happening to me, as opposed to this thing that I was actively experiencing. I often felt like I wasn’t actually in my body.

This was really hard in a lot of ways. It was difficult for me to know if anything was wrong, because I wasn’t able to know what was happening to my body.

It made answering questions from my provider nearly impossible, because when she would ask if I was having pain in a particular place, I just didn’t know.

It was also upsetting for me because I so desperately wanted the baby I was carrying, but I felt like a terrible parent for not feeling like I was connecting to it.

This isn’t uncommon, and many survivors report struggling to connect with their babies in the months after birth.

Dissociation during pregnancy can make survivors feel like something is wrong with them, and can add to feelings of being “damaged” or “broken” irreparably.

4. They May Experience Flashbacks or Triggers in Their Provider’s Office

Almost twelve weeks into my pregnancy, I had to find a new provider. I had been seeing an obstetrician up until that point, and it wasn’t going well for me.

I always see non-cismale care providers, as I don’t feel safe with men due to my experiences. This obstetrician was a woman, but she still didn’t make me feel safe.

There was no space for us to have discussions about my needs. Since this was my first pregnancy, I had no idea what to expect. I needed someone to talk to me about it.

Instead, I was treated like just another cog in the machine, and someone to move in and out of the office as quickly as possible. There were no warnings before I was touched, no explanations about what was happening and what I could expect to happen to my body.

I left each appointment feeling meek, disrespected, and incredibly unsafe.

Our Bodies, Ourselves puts it perfectly: “Our interactions with our care providers – authority figures who may expect compliance and trust – may remind us of our perpetrator or perpetrators, with whom we may have felt helpless, unequal, submissive, or overpowered.”

Other survivors, who may have been abused by a medical provider (or who may have had to spend a lot of time in hospitals as a result of their trauma) may experience different triggers than I did. Some survivors have difficulty tolerating vaginal exams.

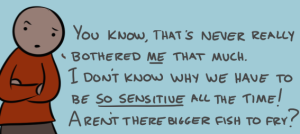

Considering the high number of women and trans folks who have experienced sexual violence, I found it shocking, appalling, and irresponsible that providers are not making it a point to ask these questions upfront, and to be trauma-informed in the way they handle patients’ bodies.

5. They May Fear Being Retraumatized While Giving Birth

The inescapable reality is that giving birth often involves the same parts of the body as sexual abuse does. This can result in flashbacks or physiological symptoms of anxiety and stress.

Similarly, certain birthing positions may remind the survivor of abuse, and this can stall or stop labor all together. The feeling of being exposed and examined can be anxiety-inducing as well.

If you feel powerless, not paid attention to, or disregarded by your providers during childbirth, this can exacerbate the post-traumatic stress reaction.

For many providers, delivering babies is routine to them, and they may feel like they know what’s best. They’ve become desensitized to the process, which can often result in them doing things without warning or asking.

Phrases commonly associated with labor – like “Relax,” “It’ll be over soon,” or “You’re doing great; we’re almost there” – can be triggering and reminiscent of things their perpetrators may have said to them.

All of this can be incredibly traumatizing for survivors of sexual violence.

6. If Someone Is Currently in a Relationship with an Abusive Partner, There Is Risk of Escalation During Pregnancy

The two most dangerous times for someone who is in an abusive relationship is when they leave and when they’re pregnant.

The pregnancy could be a result of reproductive coercion, or they may feel trapped in the relationship by the pregnancy. If the pregnancy was unplanned, this increases the person’s risk for violence.

This is where we need to see practitioners stepping up and doing a better job of assessing for these risks with pregnant patients. Asking questions beyond just “Do you feel safe at home?” can help someone with the proper domestic violence training screen for risk factors.

A provider may be able to provide local resources, and sometimes there are even domestic violence advocates available at the hospitals themselves.

A trained advocate can help someone safety plan if they’re interested, even if they don’t want to leave the relationship. This can help the person stay as safe as possible during and after their pregnancy.

And while an overbearing partner can make accessing these resources more difficult, doing so through a medical provider is a great way to lessen the suspicion of a controlling partner – because it’s not out of the ordinary for a pregnant person to be attending appointments at a hospital.

7. They May Find Pregnancy to Be Healing and Empowering

Ultimately, pregnancy (and breastfeeding afterwards) was really good for me. It made me feel like I had super powers, because my body can grow and sustain life.

For other survivors, getting familiar with and having to come face-to-face with their anatomy can help them learn to be comfortable with their bodies again.

If they have care providers that are respectful, the experience can help them learn to trust other people again, and remind them that ultimately, they are in control of their bodies.

It can also be a lesson in learning to trust your body. For me, I felt like my body had provided me with something good (a rad little baby), instead of just bad feelings.

If You’re a Survivor of Sexual Violence and Looking to Get Pregnant, Here Are Some Things to Consider

1. Look into Finding a Doula

A doula is someone who provides emotional support and care throughout pregnancy and childbirth.

They are specially trained to respond to the needs of the pregnant person, and many have experience with trauma.

Having a doula can ensure that there’s someone in the room whose entire job is to look out for your emotional well-being, and this can help mitigate some of the trauma reactions.

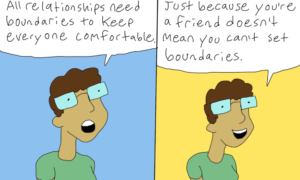

2. Have Open Conversations with Your Providers About Your History and Triggers

As I navigate the world of medical care as a trauma survivor, I’ve often struggled with knowing when to disclose my history and whether or not it’s relevant to my care. What I’ve come to realize is that it’s always relevant.

At your very first appointment, try to have a conversation with your provider about your history and needs. Bringing a support person can be helpful.

If you don’t feel safe having the conversation with your provider or you feel like your boundaries aren’t being respected, you may want to consider finding a different one.

3. Develop a Birth Plan

Since control can be hugely important for many of us, putting together a birth plan can help make us feel like we have some say over how the birth will go.

With the understanding that, in an emergency, the plan would have to change, I put together a plan that stated what the ideal experience would be for me, as well as non-negotiables (for example, I’m in recovery from alcohol and drugs, so I wanted non-narcotic pain medication unless I was having surgery).

My partner was my support person, and he advocated on my behalf, based on the plan he’d helped me draft.

Since I tend to lose my voice in triggering situations, having the plan written down allowed my partner to carry out my wishes without feeling like he was speaking over me or for me.

4. Seek Support

Counseling can be hugely important during this time.

So can seeking out support groups, whether that’s in person or online. Reading books, like When Survivors Give Birth, can also help someone feel more prepared and less alone.

5. Take Care of Yourself

Practice self-care in whatever way feels good for you. I slept a lot during my pregnancy, and not just because of normal pregnancy fatigue.

I felt safe when I was asleep and, while it might not be an ideal coping mechanism, it’s what got me through.

Listen to your body and yourself. It’s okay to be selfish and place your needs first during this time.

***

Ultimately, while pregnancy can present unique challenges and triggers for survivors of sexual trauma, the experience can be one of healing and empowerment.

I love and respect my body in ways I never could have imagined before carrying my child. It doesn’t erase what happened to me, but it has helped me make peace with a body that’s sustained so much violence.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Britni de la Cretaz is a Feature Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a feminist momma, community organizer, freelance writer, and recovered alcoholic living in Boston. She’s a founding member of Safe Hub Collective. Follow her on Twitter at @britnidlc. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more