The idea of white privilege showed up in my life long before I recognized it. That’s true for most of us, really.

Before any of us knows it, we’ve benefitted – or not – from the color skin we were born into. No greater gift. No greater sin.

Then some of us become aware, before others, that something is different, that something sets us apart.

It’s hard to put your finger on it as a young child. The words are there, the thoughts, the looks, the attitudes. But our innocent minds are still being formed, can’t yet grasp what it all means.

Later, looking back, it becomes more obvious. The words we overheard, the actions we witnessed, the pain we experienced. It all begins to make sense as our lens of prejudice and privilege comes into focus.

That was my experience.

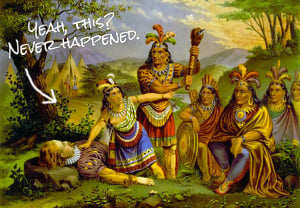

You see, I look white. By society’s perspective, I am white. It’s true that I am half white; my father was a white man. But I am also half Native American; my mother was a Native woman.

In the end, it’s what I look like, not what I think like.

Because of what I look like – white – I experience privilege. I experience “white-passing privilege.” I have no choice, no voice. It just is.

And once I realized it, I started to see it – everywhere.

Lesson #1: White Privilege Makes You Accountable

The dark night comes into clear focus.

My mother was shot and killed in front of me. I was three years old. I could only watch in horror even as my older brother, himself only five, cradled her head, pleading with her not to die.

She died anyway.

I look to the assailant. My mind fogs with the realization that it’s my father.

I didn’t understand the slur at the time, “Prairie n*gger got too big for her britches.” Her body was removed, dumped somewhere, I learned later. No one ever noticed.

Then my older brother and sister were stabbed for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, and they were the wrong color. But I was left standing.

“Not her. Halfbreed looks white.”

Their bodies, too, were dumped. Even though they were children, no one noticed. No one ever asked me where they had gone, never again mentioned their names. It was as if they had never existed.

At the age of almost seven, I now understood that what I looked like was different. I understood that I was “white” and that made me different, that made me hard to eliminate, that allowed me to survive.

I felt guilty.

Lesson #2: White Privilege Makes You Safe(r)

I started to notice what was different about me. Just as poor, just as “thugged out” as any of my friends and cohorts – but still different.

No one followed me around Nordstrom’s like they did my (black) best friend.

Even though I was a thug in the same neighborhood, the white woman didn’t hug her purse and hasten her pace when I got close. She did when my black teammate passed her on the same street.

Funny thing is, back then, I was the one she should have feared.

I spent many a long hour listening to the white family drone on about how much better off they were; after all, they were poor, but they were white.

As time moved forward, things played out differently for me in school. Even in that inner city school that warehoused us for a few hours each day, I was different than the majority of my peers. I was identified as “cute” and “mischievous” for oftentimes greater offenses than my not-so-white-looking counterparts.

I remember the time I pulled a knife on a kid who tripped me in the hall.

As I was dragged to the principal’s by two large teachers, I knew this would mean I would be kicked out. Indeed, another girl a year younger had simply gotten into a shoving match the week before and she was down in juvie.

As I entered the principal’s office, he smiled at me. “Getting yourself in trouble again, eh?”

This wasn’t my first time here.

“I guess.”

“I’m going to send you home today. Be back on Monday and leave the blade at home. You hear me?”

Shocked, I nod.

It was years later as I looked back, I recognized that it was the perception that I was white. The younger girl the week before, could not even try to pass for white.

Lesson #3: White Privilege Means You Have Potential

As I grew, my awareness grew.

I saw the prejudice and felt the pain of oppression for the poverty I experienced, for the fact that I grew up in a poor neighborhood, running drugs and guns in the “family business.”

And then I realized I didn’t want to inherit that family business.

I saw my only escape was to get an education.

Still in high school, I turned to a teacher and a counselor, both white women. They saw me, embraced my dream of higher education and did everything they could to help me along.

They told me what classes to take and guided me to teachers who cared a little more than others. They helped me learn how to do the research for which career I wanted, which colleges I could attend, and which scholarships and aide I could apply for to make it all come together.

Interestingly, I had a volleyball teammate, a friend of sorts, who also wanted to go to college. I know because we talked about it in the locker room before games. I mentioned it to my mentors. They nodded and told me there were others who had similar dreams, but I had the potential. There were only so many resources, and they needed to focus on me because I had such a great shot at making it. I shouldn’t let it take up any of my time.

I accepted their words.

I also gave my classmate as much information as I could. Her family didn’t speak English. I now understand that she and her family may not have been citizens. I don’t know that.

I do know she didn’t have a library card (most of the resources we had to access were in the library in the references and microfiche sections – this was way before computers). She wouldn’t get one. Looking back, maybe she couldn’t get one.

She also had no one helping her get through the hoops – the ACT and the arrangements to take it and the scores having to be logged and collected, the application fees, the essays. I had support lowering those hoops for me, making them easy to jump through.

No one even tried for her.

Lesson #4: White Privilege Gives You Access

I made it to college, but fell in and out of it, balancing where I came from with who I was becoming.

In one of the times I was out of college, I married my dealer (seemed like a good idea at the time) and had two children. Those children became the motivation to really change my life.

I left my abusive partner, got clean (which I use here to mean “no longer using drugs or alcohol,” the opposite of “trashed”), went on welfare, and went back to college.

I saw a huge myriad of differences in that welfare office. As a single, white-passing woman who had started college, I was given benefits that included childcare and a stipend for my book and transportation costs. Those were monumental in my success as a college student.

Having dinner at a neighbor’s house, also a single mom, we were discussing our benefits. When I mentioned my childcare benefits, she stopped short.

“What?”

“What what?”

“How did you get childcare?”

“Told my worker I needed it so I could go to class.”

“And they gave it to you?”

“Yeah. Why?”

“I can’t get childcare.”

“Have you asked for it?” I asked.

“Of course, I asked for it!” she said.

“What’d they say?”

“They told me I couldn’t have it.”

“Tell you why?”

“No.”

We talked further. She was trying to get into college. She needed the extra support from welfare to work out the childcare. The worker had flat-out told her no. No explanation. No reconsideration.

Did I mention she was a black single mother?

I came to learn that none of my friends and acquaintances of color had childcare or were considered eligible for the college bound benefits from welfare.

Many of them asked. Most of them gave up.

They were shuffled into low-level jobs that few of them kept. It was more lucrative to stay at home with their kids; at least they had food stamps and housing.

Even the process of getting (and staying) clean and sober was easier for me than for brown skinned women. I was blatantly told that I was statistically more likely to stay clean and sober than another woman who was black.

I never saw that study, but the white female worker who told me about it believed it.

If the study is real, I do wonder whether it considers the variables of institutionalized racism and classism and the likelihood that resource availability is also based on the color of your skin.

Most halfway homes out of treatment I knew of were in poor black neighborhoods. Those of us who were white, however, were placed in the one near the community college that was a lower middle class white neighborhood.

Just a coincidence, right?

Because of the leg up I received I was able to finish college, clean and sober. I was able to find a job outside of the poverty I was born into; I was able to give my children a different life.

Lesson #5: White Privilege Doesn’t End

Even on the outside of poverty, my privilege comes to bear.

I watch as I’m noticed, promoted, permitted, and encouraged over my sisters of color. Not because I’m smarter or better or more. Simply because I’m whiter.

I see how I can stand in places with my head held high, making eye contact with my male counterparts, struggling at times with the institutionalized misogyny, but not bogged down by the institutionalized racism.

I understand through my own experience that, while it takes only one privilege to benefit, the more targets you experience the impact is exacerbated. My “first” privilege of whiteness gave me the advantages I needed to get out of the poverty that bound me.

Now my middle class status allows me continued advantages that further my success.

My privilege has not been earned. It is not that I haven’t done great things, worked hard, took risks, learned, and grew. But many of those opportunities were afforded me based on the color of my skin.

There were other women of color just as willing to work hard, take risks, and learn and grow. Yet they were never given the opportunity.

It’s different when you’re white or perceived as white. Not because the pain of the oppressive experience of poverty and misogyny aren’t real, but because within the experience of classism and misogyny, the internalized oppression of those communities often identifies those members of color as “less than.”

The rules change.

We have poor black neighborhoods and poor white neighborhoods. We have the angry black woman and white women tears.

For me, I don’t identify on the inside as a member of the white community. But the color of my skin claims otherwise. I have no choice. I receive access to the privilege, I benefit from being born of a white father though I align with my Native mother.

Lesson #6: White = Privilege = Responsibility

When you meet me, you think first that I’m white and second that I’m a woman.

Think about that the next stranger you see. What do you see? Who do you see?

Honestly.

You walk into a room of six people. There are two white women, one black woman, two black men, and one white man.

Will you describe the black woman as the third person from the left or will you describe her as the black woman? Will you describe the white man as the first man on the right or as the white guy?

Consider first your own privilege. It is neither a curse nor something of which you should be ashamed. It’s a reality. It’s your reality.

Now what?

With that privilege comes, not shame or blame, but opportunity and responsibility. It is your opportunity for allyship.

To be an ally, to walk beside in support and caring, is also to be willing to recognize your own privilege for what it is: the choices, entitlements, advantages, benefits, assumptions, and expectations granted based on membership in the culturally dominant group.

You didn’t ask for it, but it is yours – and it is mine.

As an ally, we confront our own prejudice, stereotyping, and otherwise socially influenced thoughts and behaviors. We educate ourselves – not through Facebook memes or iconic representations of the experience of people of color – but through our relationships, our experiences, and the stories told within our cultures and from our children.

And when we find ourselves at a loss, with questions we can’t answer and horrors we can’t stomach, we engage in dialogue with our friends, colleagues, and those who have done or analyzed the research. We seek to understand so we can be understood, so we all can be understood.

And respected.

This is how we begin to make change: respectful relationships, honest exploration, self-discovery, expansion of our minds and experiences.

This is my experience with white privilege. I invite you to think through yours.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Leah R. Kyaio co-owns and operates With Respect, LLC, creating strengths-based solutions for violence and oppression. Her work includes professional and organizational development, team-focused consultant work, individual coaching for front line to executive personnel, and systems analysis and restructuring. To learn more about how it all comes together, visit her website.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more