I was ten years old when I began to question my attraction towards women. Although I was unsure of how to explain what I felt, I knew I just had to tell someone. One evening, as my mom and I stood on the porch looking up at the stars, I clumsily attempted to put my feelings into words.

I started with telling her how Buffy the Vampire Slayer was my favorite show and how I thought Buffy was so very beautiful and that I also really liked Spike.

Then I told her I feared I was attracted to Buffy in the same way I was attracted to Spike – and Xena the Warrior Princess (and maybe a few other butt-kicking fictional super women who I have since gotten over).

With an unconcerned and gentle voice, my mom reassured me that what I was feeling was a deep admiration for their characters and the qualities they possessed.

Of course I admired them for their strength and confidence, but I knew it was more complicated than that. I didn’t just want to be like them, I knew that someday I wanted to be with them. It all seems silly to me now, but it was so painfully and confusingly real then.

That was the end of that conversation, and I avoided talking about my attraction to more than one gender for long after that.

I didn’t even speak up during what my peers deemed the “bi phase” of high school, when a large number of people in and outside of my friend group came out as bisexual.

It wasn’t until senior year of college that I came out. I texted a trusted friend and member of the queer community then waited nervously for a response.

“I’m not surprised,” he said.

I was slightly annoyed that my latest revelation did not come as more of a shock.

“The way your eyes follow a pretty girl across a room. You’re not very good at hiding it.”

Letting go of a secret I had kept from everyone, including myself, for so long was bittersweet. I was now free to talk openly about my sexuality, but I didn’t realize that coming to terms with this part of my identity was only the beginning of my emotional battle.

I now had even more uncertainty than I did before coming out – a fear of the unknown.

I questioned how and if I would fit in with the queer community, whether those outside the queer community would change their attitudes towards me, and whether I should present myself differently in public.

Since I had never been in a (public) relationship with a woman, I especially feared not seeming legitimate enough. I was vulnerable, open to attack, and my already severe anxiety was at an all-time high.

Because funding for research on issues specifically affecting bisexual people is lacking, bisexuality is still a highly misunderstood and marginalized sexual identity.

This means that people who come out as bisexual are not only opening themselves up to attack from both the gay and lesbian community (as well as those outside of it) – they are doing it with less legal and wellness support. This is an important distinction.

Although research is disturbingly limited, the little research that does exist suggests there are three common factors contributing to the higher risk of poor mental health among bisexual people when compared to heterosexual, gay, and lesbian people. These are invisibility, lack of community, and internalized biphobia.

But before I explain these three factors in detail and exactly how they affect the mental health of bisexual people, let’s first discuss the reality of bi-specific research and some of the issues with the information that does exist.

The Lack of Bi-Specific Research

Although the number of online support groups, forums, and activism focusing on bisexual issues is reassuring, there is just not enough legitimate and unbiased bi-specific research available on mental health.

This is a huge problem considering how comforting it can be for us to learn about the way our minds work and come to the realization that we are not alone in our struggles.

The research I did manage to find led me to conclude the following:

First, much of the research done specifically about bisexual people and mental health used small sample sizes that were not indicative of the diversity among the bisexual community.

Second, the research done in the US was either difficult to access or combined the experiences of bisexual people with those of gay and lesbian people.

Third, there was much more research available about the mental health status of bisexual women than bisexual men.

Finally, much of the research I found leaned more towards the qualitative rather than the quantitative. This is important because numbers help us put things in perspective and realize the extent to which people are being affected.

Talking about putting things in perspective, here are some statistics from the 2014 Movement Advancement Project report and Rainbow Health Ontario:

- The percentage of bisexual women struggling with PTSD is 26.6% compared with 6.6% of straight women.

- Bisexual men are 6.3 times more likely than straight men to consider suicide, while gay men are 4.1 times more likely.

- Bisexual people are less likely to come out to healthcare providers, employers, family, and friends than both gay and lesbian people.

- Bisexual people may experience higher rates of childhood sexual and physical abuse.

- Bisexual people have reported higher rates of substance abuse than gay and lesbian people.

- Bisexual people who also identify as transgender are more likely to be denied healthcare services based on their bisexual identity.

- Bisexual people report higher rates of anxiety, depression, and mental illness than gay and lesbian people.

- Programs created to help bisexual people receive only 0.3% of funds given to gay and lesbian support programs.

Now that we have established the severity of this situation, let’s talk about the three ways society engages with bisexuality and how they contribute to these statistics.

1. The Dangerous Power of Invisibility

As I mentioned earlier, I didn’t come out as bisexual until I was in college. The reason for that is simple: Being bisexual was never really an option for me.

In fact, I don’t remember ever coming across the word bisexual until high school.

As a survivor of domestic and sexual abuse, I already had more than enough on my plate and I just didn’t have the emotional stamina to deal with this other thing that lingered in the darkest corner of my mind.

My conversations with counselors and psychiatrists were always the same. I would talk about my haunting past and analyzed how I thought my experiences with abuse were affecting my mental health.

It was a relief to find out my problems had names: Anxiety, PTSD, and ADD. Except for the part where I still didn’t feel whole. It wasn’t until recently that I began to understand how much this invisibility affected me mentally and emotionally.

Being invisible in this one aspect of my identity made the rest of me invisible. It was like a barrier that reminded me I could not be myself until I could be all of myself at the same time.

Because I did not allow myself to be the complete me that I am today, I reverted to the partial me that I was as the abused little girl who could not protect herself. The little girl who could only understand her identity in the context of the life being forced upon her.

That is the power of bisexual invisibility: We exist unseen, erased, and misunderstood, often even to ourselves.

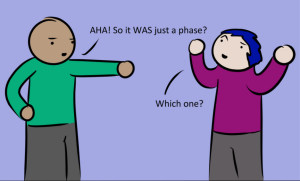

If we look closely, we can see this erasure at play in media depictions of bisexual characters. Rather than write a character as bisexual, a potentially bisexual character will often be depicted as a gay or lesbian who has yet to come out.

If a character is identified as bisexual, it is usually to paint the character as indecisive, promiscuous, and untrustworthy.

This erasure also exists in the labels forced upon public figures. Just look up “X Famous Lesbians Who Were Once Married to Men” or “X Famous Gay Men Who Were Once Married to Women.”

At least one of the names listed is of a famous person who has publicly come out as bisexual, but whose sexual identity has been publicly ignored on countless occasions based on their current and past relationships.

2. Limited Access to Community and Safer Spaces

My sister came out as lesbian at a pretty young age. Though she has a rebellious exterior, I know it was not an easy thing to do. But because she is who she is and always has been unapologetically so, she didn’t seem fazed much by the reactions she received.

I remember wishing I were as brave as her. I wished I didn’t care as much what people thought of me. If it weren’t for that pesky need to be accepted and my debilitating anxiety, I probably would have come out earlier.

My anxiety meant that I had friends, but never quite trusted any of them with my deepest feelings, especially those concerning my sexuality, for fear of judgment or rejection.

Even if I did allow myself to belong, there was no bisexual community advertised like the Gay and Straight Alliance group at my high school that many of my friends belonged to. I did go to a few meetings, but I never felt a part of their community.

So what happens when we do find community, but that community isn’t as supportive as expected?

Bisexual people find themselves belonging and yet, not really belonging within the gay and lesbian community because their sexuality is often viewed as a threat.

This is based on the common misconception that bisexual promiscuity leads to the spread of STIs. It is also based on the misconception that bisexual indecisiveness reflects negatively on monosexual identities.

So not only are bisexual people made to feel invisible within the heterosexual community, but they must also be cautious of the seemingly safe spaces they find within other monosexual communities.

3. Painful Effects of Internalized Biphobia

I knew being bisexual was not a good thing way before I had even heard the word.

I learned that most people are straight, and that’s great. I learned that some people are gay or lesbian and that’s apparently not as great, but tolerable – as long as they don’t try to get married.

However, growing up, I learned that being bisexual meant you were a slut, you were just trying to get attention, and that it was just a phase that would soon fade.

Knowing this, I was definitely judgmental towards my friends who came out as bi during the high school “bi phase.”

When I first began to acknowledge my personal attractions, I was disgusted with myself. I felt dirty. I felt like a slut for even having those thoughts. There must be something wrong with me because of the abuse. I must be damaged and now I’ll have to hide my promiscuity for the rest of my life.

When all we know about bisexuality is negative, we start to feel that maybe society is right.

This is not our fault.

The fault lies in the lack of accurate depictions of bisexuality by content creators who don’t understand the diversity and complexities of this identity.

The false truths we decode from negatively encoded messages we receive about bisexuality tell us that bisexual people are cheaters, liars, and promiscuous sluts.

Bisexual people then absorb those stereotypes and become distrustful and ashamed of their own identity. This internalized biphobia prevents the bisexual community from becoming exactly that – a community, a safe space, a support system. It pins us against each other and against ourselves.

Path Towards Inclusion and Healing

Although it took me a while to find a bisexual community that truly understood my struggles, I was lucky to have the support I did when coming out. I know that many are not as lucky.

Today I am a part of the first bisexual book club at my university. It is currently a small group, but we have high hopes for its growth. We are a part of a quiet revolution, building supportive communities for bisexual people to thrive in and increasing bi visibility wherever we go.

Yes, progress is happening. However, we must keep in mind that the reason why this issue is slowly but surely becoming a priority is based on our choices.

That being said, here are some choices we can all make to eradicate biphobia and exclusion:

- If you are a health provider, conduct bi-specific training for your staff. This will help bisexual clients feel more at ease when seeking services.

- Publicize bi-specific services offered.

- Contribute to funding for bi-specific research if you are in a position to do so.

- Don’t assume! A person’s current partner says nothing about their sexual identity.

- Listen to the stories of bisexual people. You might learn something that will help you be a better ally in future encounters with biphobia.

- Never minimize, invalidate, or dismiss someone who comes out to you as bisexual. You might be the only person they trust with this very sacred information.

- Ask questions. Sometimes to feel accepted we just need an indication that someone cares about our experiences and is making an effort to learn.

- Call out biphopic depictions and behavior whenever you see it in media or elsewhere.

If we make a conscious effort, I know it is possible for bisexual people to find the support we need and ease the burden of internalized biphobia.

It is our responsibility to make a difference, even if you don’t identify as bisexual yourself. Movements are more successful with an outside presence of supporters who believe in the cause as strongly as those they are supporting.

We need drastic change and we need it now. Not just for bisexual people, but for all sexual identity minorities who are currently fighting for visibility and struggling to find community.

It is imperative we keep in mind that together we are stronger than when we allow ourselves and others to stand alone.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Katherine Garcia is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a recent college graduate with a BA in Radio, TV, Film and soon to be graduate school student pursuing a Masters in Women and Gender Studies. She is passionate about LGBTQIA+ rights, domestic violence advocacy, Latinx issues, and mental health awareness, as well as 80s hair metal, used book stores, astrology, and chocolate. You can follow her on Twitter @TheLazyVegan1.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more