My sister, Creigh, was 17 when she was first discriminated against for being autistic.

It was at an autism support group. Creigh had been caring for the group’s children for months by that point, playing with them while their parents talked. One night, a mother who was new to the group refused to let my sister take care of her son.

I was confused. Her son was clearly bored, and equally clearly distracting her and the other members from the meeting. I couldn’t figure out what the issue was, but brushed it off as a fluke.

At the end of the meeting, the mother approached my sister and apologized, saying she hadn’t trusted her because she thought Creigh was autistic.

Here’s the thing: She’s not.

But because of the mere perception of disability, Creigh was no longer trustworthy. With one word, my sister’s competence had been stripped away, only to be replaced by ignorance and fear.

She was the same person as she always was, but suddenly she was being judged through the lens of stigma rather than ability.

Here’s the other thing: The reason she’d thought my sister was autistic is because she got my name confused with my sister’s.

Up until that point, Creigh hadn’t realized how differently the world treated the two of us. It would take years before she and I would learn the label for this difference: privilege.

For one short night, my sister had gotten the tiniest glimpse at my everyday existence as an autistic person. But that was just one night. One instance when the discriminator actually apologized for as soon as she realized her error.

Further, it only occurred to her to apologize for the mix-up, not the discrimination. And that’s messed up.

But fighting this type of discrimination isn’t just a one-night mistake for me; it’s a battle that I was forced to wage from the instant of my birth, like it or not.

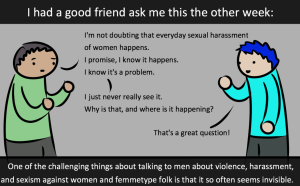

Yet, despite having been with me every step of the way, it had never occurred to my sister to think of how differently society treated us.

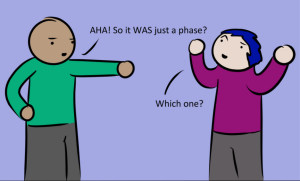

Granted, my sister isn’t neurotypical either – it’s just that Creigh’s deviations from the typical neurology are less obvious. Her moderate anxiety disorders can often fly under the radar in a way that autism often can’t. Yes, those come with their own difficulties and microaggressions, but they are not the more blatant, in-your-face discrimination I’ve encountered.

Even within neuroatypical experiences, there are differing gradients of privilege and oppression.

Here we’ll cover some of the more blatant examples of neurotypical privilege out there. Not every neurotypical person experiences a lack of problems in these areas, and not every neuratypical person has these problems. However, these are incredibly common and fly under the radar for those who are neurotypical.

But, Wait, I’m Not Privileged!

“How can I be privileged when I, too, have faced these same struggles due to race/gender/poverty/and more?” you may say.

And you would be right. Many of these privileges are multi-factorial. For example, when I talked to my Black counselor about the stares I get in public, she pointed out that she, too, had to face those same probing eyes.

But facing struggles in other areas doesn’t eliminate your neurotypical privilege.

It just means you are oppressed in other ways which can lead to similar problems. This is a reason to expand the fight for equal rights, not to deny the struggles of other groups.

So now that we’ve addressed any objections, let’s go ahead and look at the top eight able privileges.

1. Being Able to Go Outside Without Getting Stared At Because of Your Disability

When my sister is walking outside alone, she goes unnoticed, but as soon as I join her – despite my lack of physical differences – we draw stares.

Due to my anxiety, I need hugs with firm pressure to keep my calm. The instant I do so, however, people start staring at us.

This makes me more anxious, which makes me require more hugs or I start flapping my hands – and then even more people begin to stare, and then… You get the idea.

It’s a vicious cycle, one which typically ends with my having to run out to the car while my sister finishes the rest of the grocery shopping.

When my sister goes outside by herself, though? No stares, not even a second glace. That’s neurotypical privilege at work.

2. Being Talked To in a Typical, Non-Infantilizing Manner

We covered this one already in our article about infantilization, but this is a big problem disabled people face – being spoken to like they’re small children, regardless of their age or cognitive abilities.

And that’s not okay.

Even if a person actually is intellectually disabled, that doesn’t eliminate their age. Unless you’re actually talking to a small child, there’s no reason to talk to someone as though their adulthood is eliminated by their disability.

So the next time you have a conversation with a stranger and they address you without only using small words, a sing-song voice, and telling you how adorable you are, thank your able privilege.

3. Being Able to Attend Classes in the Same Room as Your Peers

Even ignoring the barriers to entering locations, there are still huge barriers to studying and working alongside others.

My mother had to fight the guidance counselor so I could take advanced placement classes. Because I was disabled with an exceptional student status and the counselor saw that and said, “Oh, no, they (read: code for students with disabilities) don’t take AP classes.”

Regardless of my great grades, I was being denied because I had a disability. When I finally got into those classes, by the way, I passed them with flying colors.

What’s more, when I was in elementary school, the school tried to kick me out. Parents had complained about my taking classes with able children, and so the school called a meeting during which they tried to remove me from the school. My family fought for me to remain, and instead I was ‘merely’ put on probation for a year.

I knew that the school had attempted to kick me out, knew that my teachers had testified towards that end, and unsurprisingly, that was also a year during which I fell into a deep depression.

Just a few years before, my sister had attended that same elementary school as me. She had the same teachers, who treated her with kindness and compassion. That’s right – even at the ripe old age of ten, she was unknowingly experiencing neurotypical privilege.

And once you graduate, the ableism doesn’t cease. Remember being told that social networking is the most important factor to getting a job? That is a system inherently built on privilege – a system which discriminates against neurodivergent people.

Even if you apply for a job without having networked your way there, you still have the interview to conquer. And that, for neurodivergent people, can be an almost insurmountable task.

An interview is not a test of one’s qualifications, but of one’s social skills. It requires typical body language, slick answers, and essentially fitting social norms. These are all areas where neurodivergent people often—well—diverge.

And just like that, you’re eliminated from the running, not because of your abilities, but because of your differences.

Sure, employers can’t say that they aren’t hiring you because of your disability. But as long as they cite another valid sounding reason, they can be motivated by discriminatory intentions all they like.

4. Hopping in the Car to Go Somewhere

Every time you decide that you want to go somewhere and get into our car without a second thought, we’re exercising neurotypical privilege. Because for many neurodivergent people, it’s not that simple.

We may have such a degree of depression or anxiety that we cannot drive – or we may simply not have our own car, not be able to afford one because of the lack of well-paying work.

We may not be able to focus enough to drive safely, or might have to battle intrusive thoughts telling us to slam our cars into a tree the whole way there.

How about taking the bus? Well, if you have a disability, getting to the bus stop is can be much more difficult, perhaps even impossible. Buses for the disabled exist for that reason, but not all disabled people qualify for them, and they can also be unreliable.

From my perspective, I feel like shouting at people who expect me to be able to drive. I’m sorry I’m not a) rich enough to have a chauffeur or b) able to teleport, but I’m too anxious to be able to drive. But I should still be able to access things outside of my home.

I hate not being able to do the same things as my friends because of that. I would have to beg for rides from friends to go get food. So me getting breakfast and dinner was dependent upon me begging people for rides. That’s messed up. That’s really messed up.

Due to that same anxiety, even if I could make it to the bus stop, my agoraphobia would send me into fight or flight for however long it took the bus to arrive.

We may not think about it, but easy transportation can definitely be an element of neurotypical privilege.

5. Not Being Blamed for Your Own Murder

I wish this didn’t have to be said. I so, so wish that. But it does.

Horrifyingly, every time a disabled person is murdered by their parents, the media prints a story sympathizing with the parents’ situation.

Worse yet, many disability organizations and parents of disabled children express their sympathy, not for the murdered disabled people – but for their murderers.

What?!

If you feel overwhelmed caring for someone disabled, get help for yourself. If you’re considering murdering them, check yourself into a hospital, drop your child off at a police station and leave, call a crisis line – do anything other than murder them.

There is no reason to kill your child. Acting like their disability somehow makes that acceptable is just wrong and hurtful in so many ways.

6. Choosing a Life Partner and to Have Children, If Desired

Even ignoring the difficulties that discrimination can make in finding a partner, or that health problems can have on childbirth, these are both areas of privilege for able people.

Society teaches disabled people that both of these are somehow off-limits for them. Just look at the ways my sister and I were treated growing up and the discrepancy is clear.

Like most girls, society taught my sister that when she grew up she was going to find a husband and have babies. As she grew older, people continually asked if she had found a nice young man to settle down with. Whenever Creigh played with children, they would remark on what a good mother she would be some day.

Yes, this is problematic, but it is typical.

My experience was quite the opposite. Explicitly and implicitly I was taught that I was worthy of neither of these.

When I expressed having a crush on a boy, people would smile condescendingly and say how cute it was. It felt like they were saying, “Aw, look, she thinks she’s people!”

What’s more, when I played with children and expressed how much I wanted to be a mother, I was told through both hints and straight out that I would be unfit. The only reason cited for this was my disability.

Because I’m autistic and disabled people automatically disqualified me from motherhood.

I was told that I would be an unfit mother so many times that I even began to believe it.

And even when the disabled person does, in fact, find their life partner or have a child, society still puts up barriers. Just look at this example of a married disabled couple denied the right to live together.

So yes, settling down with a partner and having children without facing backlash are examples of neurotypical privilege.

7. Being in Control of Your Life

When I was approaching adulthood, I was terrified that our mother would apply for guardianship over me. This would legally rip away all of my rights to making choices over my life, and would be nigh impossible for me to reverse.

Thankfully, our mother respected my abilities too much to do so, despite pressure from society, but many are not so lucky.

What’s worse, if our mother had applied for such guardianship, she would have won it. The psychologist who examined me at the time viewed me through a veil of condescension and ableism.

In his report, he said I would never be able to live alone and likely wouldn’t be able to make it through college. I went on to do both.

But even without legally removing a disabled person’s rights, you now know the many ways that society denies the right to a full life to so many neurodivergent people.

***

So many paths open to neurotypical are closed or made treacherous to the neurodivergent. And yet the able don’t see this, at least, not until they join the ranks of the neurodivergent themselves.

The mere act of exerting control over your life can be an act of rebellion against the kyriarchical system for disabled people. So every time you drive your car, date, go to work, or even open a door – thank your privilege.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Caley Farinas is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s a recent graduate with a Bachelor’s in Public Health who writes about the effect society has on the “disabled.” Caley writes from her experience as an Autistic woman with dysgraphia and anxiety disorders. Because of these disabilities, it is hard for her to write and she gets assistance from her sister Creigh in writing/typing. That said, any words that you see attributed to her are her own, and she edits and approves anything her sister Creigh types. You can see more of Caley and Creigh’s writing on their website Autism Spectrum Explained and their Facebook page.

Creigh Farinas is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s a graduate student pursuing a Master’s degree in Speech Language Pathology and who already has a B.A. in Psychology and a post-baccalaureate in Communication Sciences and Disorders. Creigh is still learning more every day, and her sister Caley reads, edits, and approves everything that Creigh writes about disabilities. You can see more of Creigh and Caley’s writing at Autism Spectrum Explained.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more