“Contemporary art has far more nude women than men. It’s not fair,” I vented to a friend over ice cream one night.

“Oh, that’s just because women are more aesthetically pleasing,” she shrugged, picking up her spoon.

“Well, that’s what we’re taught to think.”

“No, I’ve always thought that,” she recalled. “I mean, I’m not saying women should be objectified or anything.”

I believed her, but the fact that you’ve thought something from a young age doesn’t mean culture had no influence.

And though she didn’t intend to objectify women, the widespread belief that women are “the fair(er) sex” does objectify them.

Not to mention, it equates sex with gender and disregards non-binary, gender-nonconforming, and agender folks by equating women with people with vaginas and contrasting them with men.

You may have heard this explanation for women’s disproportionate sexualization in pop culture before: that women are just more pleasant to look at.

You may have even heard it in a feminist context. Another friend once told me that it’s unfair that women work harder to look good when they look better in the first place. And a guy I met in a bar once said it makes no sense to hold anything against lesbians because “women are much hotter,” so of course even women will be attracted to them.

That second sentiment, by the way, isn’t just one expressed by ignorant outsiders. Author Rita Mae Brown said, “I became a lesbian because of women, because women are beautiful, strong, and compassionate.”

On top of that, one woman told me that “men are horny bastards” because “women’s bodies are beautiful” – in other words, it’s no wonder men objectify us when our bodies are asking for it.

As this last statement shows, the notion that women are more pleasant to look at can have insidious implications. And that’s true even when people try to employ it toward feminist ends.

People aren’t objectifying women by personally finding them more attractive. However, the view that women are objectively, universally “the fair(er) sex” maintains a status quo where women’s bodies are more often sexualized, whether its advocates intend to or not.

My friend’s comment about art, for example, serves to defend the gender imbalance of nudes in museums. As the feminist art activist group The Guerilla Girls famously pointed out, 76% of the nudes in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Modern Art section are women, while only 4% of the artists with work showcased there are women.

And those two statistics are related.

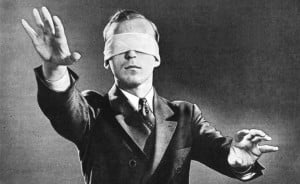

Nude drawings and scantily clad magazine covers may seem innocent, but nudity and clothedness have long symbolized power dynamics. The imbalance of public nudity makes “women’s bodies vulnerable while men’s are protected,” Naomi Wolf explains in The Beauty Myth.

“Cross-culturally, unequal nakedness almost always expresses power relations: In modern jails, male prisoners are stripped in front of clothed prison guards; in the antebellum South, young black male slaves were naked while serving the clothed white masters at table,” she writes.

“To live in a culture in which women are routinely naked where men aren’t is to learn inequality in little ways all day long. So even if we agree that sexual imagery is in fact a language, it is clearly one that is already heavily edited to protect men’s sexual – and hence social – confidence while undermining that of women.”

These social hierarchies influence ideals of beauty, which, in turn, can influence our individual taste, even if it feels like we’ve had this taste our whole lives. When we explain away our culture’s obsession with women’s bodies as the result of innate preferences, we obscure injustice by training ourselves to view systems of oppression as human nature.

And whenever we consider something human nature, we block ourselves off from questioning it. Gender inequality becomes part of the air we breathe, and we don’t even realize it’s suffocating us.

To be clear, this is not a diatribe against people who are attracted to women. I’m talking not about individual sexual preferences, but about societal ideals of beauty. These two things are sometimes related, but regardless, we’re all entitled to our preferences, even when they have problematic roots.

However, we run into some problems when we assume that the affinity for looking at women is universal and that its normalization is devoid of oppressive power dynamics. So here are some of these problems with the stereotype of women as “the fair(er) sex.”

1. It Perpetuates the Objectification of Women

Claims like “women are more beautiful” and “women are just more aesthetically pleasing” are often used to explain away the imbalance of nudity not only in art, but also in porn, movies, magazines, and television.

Pop culture is replete with the “clothed male, naked female” trope. Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” video is just one example of mainstream media’s tendency to dress men, while leaving women naked and vulnerable.

Movies that display a man’s full-frontal nudity are also far more likely to get an R or NC-17 rating than those that portray a woman this way.

And we need to start seeing that for what it is: a problem.

This double standard sends the message that men are supposed to look and women are supposed to be looked at. It deems women passive objects of desire and deprives them of their right to have desires of their own.

When we say that this imbalance exists because of an innate human preference for women’s bodies, we brush the problem aside and depict the objectification of women as the natural order of things.

2. It Marginalizes Sexual Preferences That Differ from Those of Straight Men

Here’s a little lesson in feminist film theory: The mainstream media depicts the world through an imaginary “male gaze,” which is not necessarily the perspective of most men, but rather, society’s notion of a “normal” man’s perspective.

As such, the male gaze is a heterosexual one, and non-binary people are rendered invisible, neither subjects nor objects of the gaze.

Films, TV, and other visual media prompt everyone, including straight women, to see through the eyes of a straight man, both literally and figuratively.

This is accomplished through the camera’s focus on women’s bodies, the script’s unsympathetic portrayals of women, underdeveloped women characters, and a number of other conventions.

It’s no wonder so many people believe women are more aesthetically pleasing when they’re taught to view the world as a straight man would.

Yet despite this cultural norm, many still don’t see things that way. Many people like looking at men. Many people like looking at those who don’t identify as women or men. Many people have no preference. Those perspectives are all equally valid.

While aesthetic taste and sexual preference can be distinct, they’re often related. So, when we say women are objectively more aesthetically pleasing than men – and such statements don’t even acknowledge gender-nonconforming people – we erase people who aren’t predominantly attracted to women.

3. It Universalizes Contemporary Western Culture

When we say “women are more attractive,” what we really often mean is, “Women are considered more attractive in contemporary Western culture.” Because not all cultures see it the same way.

Anyone who thinks the abundance of women nudes in art is a result of natural aesthetic preferences should see the nude statues of Ancient Greece, where athletic men’s bodies were idealized more than anything.

Today, the Wodaabe people of Africa hold beauty contests for men judged by women.

Even in parts of Europe compared to the United States, there’s less of a double standard in the value placed on gendered appearances.

For example, in English, using the appearance-related words typically designated for women toward men can be an insult. Calling a man “pretty” or “beautiful” is said to feminize him.

But in Italian and Spanish, it is normal to call a man “bello,” the equivalent of the feminine “bella,” and in French, the words are “beau” and “belle.” All three of these countries are known for having more fashionable men as well.

I say this not to endorse the objectification of men, but to argue that the disproportionate objectification of women is not the human race’s biological destiny.

When we say that the beliefs held by people of our own place and time are natural, what we’re really claiming is that our culture is right and others are wrong.

4. It Uses a Normative Definition of ‘Woman’

The idea that women as a group are more aesthetically pleasing relies on the presumption that all women look similar – and that all people with vaginas are women.

People who say that women’s bodies are more beautiful are typically imagining a particular kind of woman.

They’re not imagining an old, fat, flat-chested trans woman of color sitting in a wheelchair. They’re picturing a slender, curvy, young, white, able-bodied, cisgender woman – the kind you typically see in art and on TV.

Once we realize how diverse the group we classify as “women” is, though, it seems ridiculous to make any sweeping generalization about women’s appearances.

When we say that women are by nature beautiful, we exclude women who don’t fit society’s definition of that word.

Everyone is beautiful, yet few are deemed beautiful by conventional standards. And when people say that women are more beautiful, they’re usually referring to those select few women they see in the media every day.

But women who don’t look like that are still women.

5. It Puts Men Down and Erases Gender-Nonconforming People

“Women look like beautiful, soft, gorgeous angels when they’re naked. We look like hairy ogres or little scrawny trolls,” Jason Mraz once wrote in Cosmo.

While it’s problematic to objectify one gender by heralding them as more pleasant to look at, it’s also problematic to consider one gender unattractive – or to measure anyone according to societal beauty standards.

Body positivity dictates that everyone deserves to feel good about their body, including men and gender-nonconforming people, and the myth of women’s aesthetic superiority excludes them.

Mraz’s viewpoint can not only make men insecure, as he himself mentions, but also perpetuate that same old stereotype that men’s bodies are for doing while women’s are for being looked at.

It’s a poisonous combination: criticism with a side of objectification.

In addition to deeming men unattractive, the “fair(er) sex” school of thought completely erases gender-nonconforming people by positioning women in contrast to men and equating gender identity with genitals.

When we acknowledge that there are many different genders and that people with all different bodies can identify with any of them, it becomes impossible to make judgments about which gender has the most attractive body.

The “fair(er) sex” trope relies on the premises that there are only two sexes, that there are only two genders, and that these categories are synonymous – because in the phrase “fair(er) sex,” “sex” also means “gender.” All three of these premises are false.

***

It may be hard to believe that the “fair(er) sex” philosophy is destructive when it shows up in so many contexts meant to empower women.

But like all forms of benevolent sexism, these gestures of support only serve to maintain a status quo in which stereotypical straight men’s perspectives are universalized, women are objects (not subjects) of desire, and gender non-conforming people are invisabilized.

A truly feminist, body-positive viewpoint says that everybody can be beautiful in their own way, and no group is objectively more attractive than any other. After all, beauty is personal and subjective – sweeping generalizations just don’t work.

And we all deserve to feel beautiful, no matter what gender we are.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Suzannah Weiss is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a New York-based writer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Salon, Seventeen, Buzzfeed, The Huffington Post, Bustle, and more. She holds degrees in Gender and Sexuality Studies, Modern Culture and Media, and Cognitive Neuroscience from Brown University. You can follow her on Twitter @suzannahweiss.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more