Source: iStock

I am at work and a man wearing a suit comes up to the register to pay for his food. He hands me a $50 bill and I hold it up to the light to make sure it’s not counterfeit.

He looks at me like my actions are absurd and tells me a story about the time he unknowingly used a counterfeit bill and the police were called.

He was baffled by this occurrence because, according to him – and most of society – he doesn’t look like the type to purposely pay with counterfeit money.

He told me this in order to let me know that he wasn’t used to being treated like everyone else. His appearance had afforded him privileges in the past and he was upset that he wasn’t receiving the benefit of the doubt he was entitled to.

What was especially troubling about his reaction was the connection he seemed to make between a person’s morality and their wealth.

We live in world where people who look like him, and who dress the way he does, are perceived to be safer, less criminal, and more reliable than everyone else.

This value set is rooted in capitalistic notions of meritocracy. We’re taught that people who have a lot are successful because they are hardworking, honest, good-hearted people and have earned the right to be treated like the privileged elite – at everyone else’s expense.

And rather than reject and dismantle classism and economic privilege, we sustain it by aspiring to emulate the wealthy in how we dress and present ourselves to the world. We try to look like people who spend loads of money to look like they are better than us, so we can have access to the respect and dignity our culture affords them.

And that is not only problematic, it is oppressive. Here are six reasons why.

1. It Implies That We Are Frauds When We Wear Nice Clothes

A few years ago, I was given a coach purse for Christmas. I was grateful, but also worried I would have nothing to wear it with. It just didn’t feel right to use such an expensive purse with just any outfit.

So I bought an expensive coat to go with it. Then I bought some expensive boots.

For a little while, I was treated like I was a part of the elite group of people that society tends to think automatically deserves respect. It was a few hours free from the constant classist microaggressions directed at the poor, and a brief taste of what social class privilege could feel like.

However, when I got into my rusted and loud 1997 Geo Prizm, I felt like a fraud. I knew that even though I was dressed like an upwardly mobile, young professional who wore fancy new accessories, my car would reveal my true economic status to all who passed by.

I did not actually have the sort of job that would afford me the resources to dress the way we’re told that women in my age group should dress.

And in that moment, I felt ashamed. Like I was not where I was supposed to be in life.

I felt like I was not successful. Like I wasn’t as committed or hard working as other people who could actually afford clothes like these. Like I didn’t actually deserve the respect that people offer folks who are able to successfully assimilate into the status quo.

And that’s exactly the oppressive value system we’re taught by television, meritocratic rags-to-riches stories, and the academic industrial complex all the time. That if you work hard and play by the rules, you’ll have nice things. And those of us who can’t access those things haven’t worked hard enough.

By aspiring to look rich, we’re actually aspiring to look like we have the positive qualities assigned to rich people – which only works if we believe that non-rich people don’t have those qualities.

My internalization of this classist programming lead me to feel, if only briefly, that I didn’t deserve basic respect and human dignity that we feel like the wealthy are entitled to.

It left me feeling like I was a fraud, and that everyone who knew my true economic status would know it and judge me for attempting to disguise my true circumstances. They would wonder how dare she pretend to be something she isn’t – how dare she have those things.

What this means for people who cannot attain the rich look quickly and all at once is that they risk being viewed as frauds for only partially meeting the qualifications.

Partially meeting the qualifications more often than not registers as taking advantage of the system rather than assuming this person has worked hard to buy the expensive things they do own.

2. It Implies Those Who Look Rich Are More Capable And Responsible In A Professional Setting

Professional, put together, well-fitted – these are the things that make us worthy of respect.

Or so we have been conditioned to believe by the rules and expectations we are taught will result in a successful job interview. This idea permeates in social settings as well as the work environment.

We are exposed to this all the time when society sends us messages about how to be successful. Interview tips tell us looking professional is the same thing as looking well-off, and looking well-off is the same thing as being competent.

Not only are people who look rich perceived as more responsible and capable, they are assumed to be more extroverted, charismatic, and experienced. Those who don’t look the part are assumed to be less capable, more socially awkward or reserved, and less experienced.

Basically, the idea is that being qualified to do a job somehow matters less than looking qualified.

This is harmful because it allows us to ignore the potential in people, but also because it makes it easier for us to stereotype them. This stereotyping is what makes discriminatory hiring practices possible and prevents people from improving their circumstances.

People of color are especially affected by this because they don’t belong to the dominant culture and so their behaviors and physical appearance are more likely to be judged harshly and unfairly.

3. It Implies That People Who Look Rich Are Smarter And More Deserving Of Respect

Society holds certain expectations of what authority figures should look like. It is how we determine whether someone is fit to lead and deserving of our respect.

For example, the teacher who is wearing what would be considered professional attire is perceived as more qualified and worthy of respect by their students – someone who should be taken seriously.

Female teachers in particular are subjected to oppressive expectations about what they wear and are often criticized for what they look like rather than their effectiveness as an educator. Male teachers, however, are afforded more flexibility without sacrificing the respect and admiration from students.

Unsurprisingly, the advice tips that tell us how to look smarter are very similar to the ones that tell us how to look richer.

Both reinforce the idea that the clothes we buy are a direct signifier of our intelligence and wealth. This is so dangerous in our society. Some people vote for presidents and other people in positions of power based on this stuff!

It can also impact the amount of effort we make to get where we want to be. It becomes easier to look the part of the rich person who is already perceived to be smarter and more educated than to spend the time actually proving it.

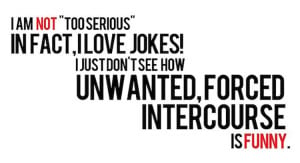

4. It Implies People Who Look Rich Are Less Likely To Commit Crimes

When I go into Wal-Mart, more often than not, I notice two things happening. First, people being followed because of their race. Second, people being followed because of what they are wearing.

These two things are interconnected when it comes to criminalization because of the racialization of clothing styles.

For example, take a look at the clothing brand SouthPole. It was founded by two Korean immigrants and quickly became one of the most popular urban and hip-hop brand names. However, public opinion shows how the racialization of this brand and its association with Blackness created an image – and not a good one.

A search of the brand name on Urbandictionary.com pulls up 20 words related to SouthPole. Some of the words on the list were gangsta, ghetto, hood, slut, and wigger. These are the words used to describe people who wear these clothes.

The association with Blackness is enough to mark them and set off a warning signal that this person is up to no good and should be watched carefully.

We have been conditioned to form an image in our minds of what a criminal looks like, and it’s most likely not an image of a person wearing Gucci or Prada.

But even if it were, we would be more willing to let them prove their innocence before jumping to a guilty verdict.

This is how criminalization operates – it is how we transform a person into a criminal while being guided by race and class bias. This bias is the difference between legal crimes and punishable crimes. These legal crimes affect all sectors of society from discriminatory legislation to corrupt corporation practices.

But these legal crimes are on a separate category labeled “white collar crimes” – victimless crimes. These crimes are committed by the privileged dominant group, or the innocent until proven guilty. With their privilege, they have the power to escape punishment.

So who is deserving of punishment? They are the people associated with punishable crimes involving drugs, violence, and theft – the poor and people of color. This is what we mean by the “criminal type.”

This is why the public goes wild with disbelief when we hear about well-off or wealthy people who commit really serious crimes because they just “don’t look like the type.”

Take the Martha Stewart and ImClone case, for example. The way the media described her crime as a scandal focused attention more on the question of her reputation as a celebrity rather than the crime itself.

And of course her fame garnered supporters who justified her actions and labeled the crime a victimless one – meaning unworthy of punishment.

5. It Implies People Who Look Rich And Benefit From Class Privilege Have More Worthwhile Goals

I grew up in a low-income household where most of the clothes I owned were either hand-me-downs or from the thrift store vouchers donated to our family. I was rarely ever wearing the most current and popular styles or name brands and I didn’t really care.

However, something changed when I decided I wanted to go to college, when I decided I wanted a “real career.” I started wearing dress pants and sensible shoes. I started looking at clothes tags to make sure I was getting the name brand stuff. People started assuming I was a teacher when I walked down the hall.

Why was I doing this?

Because I knew and had been told that this is what it takes to be taken seriously. Being taken seriously meant looking the part of a well-off person.

The people I knew of that were successful in every aspect of their lives had this in common. They looked the part. They looked financially stable.

I figured that maybe if I looked the part the rest would just come in time with minimal effort.

This is how society categorizes the worthiness of our career goals. The better dressed we have to be to get a certain job, the prouder we should be to pursue it. It also means we tend to look down upon people with jobs that don’t require the same level of implied sophistication.

This career goal privilege affects those who may have higher aspirations, but are unable to pursue them.

It ignores the fact that there are many barriers for people who don’t have class privilege that prevent them from achieving their goals – it doesn’t mean they don’t still have them.

6. It Implies People Who Look Rich Are More Responsible and Financially Independent

We tend to respect people who look rich based on the assumption that they are stable and independent. They are people we can count on to make the right choices.

Those who don’t look rich are viewed as irresponsible – comparable to children spending all their allowance on candy then asking for more.

This infantilizes people who don’t benefit from the privilege of being perceived as rich, and we see this in the limitations placed on what people are allowed to purchase with government aid.

For example, people receiving temporary financial assistance are prohibited from using those benefits to make certain purchases and some states even limit the amount of money that can be withdrawn per day. This implies people receiving aid are not responsible enough to make good choices and that decisions must be made for them.

This is also visible in the language we use when talking about issues concerning poor people.

Another Google search brought up a disturbing amount of results beginning with the words, “Should poor people be allowed to…”

“Should poor people be allowed to have children?” “Should poor people be allowed to vote?” “What should poor people be allowed to eat?”

The fact that we think we should have any say on the way poor people live their lives says a lot about our perception of them and their ability to be independent beings, financially and otherwise. It also makes it permissible to continue discriminating against them.

***

I want to emphasize that I do not believe it is a negative thing to take pride in the way we look. What we wear should make us feel good. It should make us feel confident.

What it shouldn’t do is determine our capabilities or our goals in life. Our clothes shouldn’t be the difference between a job offer and a rejection.

In college, I had a professor who I admired for his confidence and the fact he didn’t seem to care at all what people thought of him. His class was probably the most memorable of my entire college experience.

He wore the same outfit every single day.

What I’m saying here is that our clothes and our ability to look wealthy shouldn’t signify our worth. We all have much more to contribute to the world than our clothes, regardless of how much money we have.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Katherine Garcia is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a recent college graduate with a BA in Radio, TV, Film and soon to be graduate school student pursuing a Masters in Women and Gender Studies. She is passionate about LGBTQIA+ rights, domestic violence advocacy, Latinx issues, and mental health awareness, as well as 80s hair metal, used book stores, astrology, and chocolate. You can follow her on Twitter @TheLazyVegan1.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more