(Content warning: discussion of trauma, violence, suicide)

When I was nineteen years old, I enrolled in a class called Abnormal Psychology. It was a survey course on mental illness, and it was the first step in my path to becoming a social worker and psychotherapist.

At the time, though, I wasn’t really all that focused on learning how to analyze other people — I was much more interested in learning how to understand myself.

My whole life, I had struggled with patterns of behavior and emotion that I knew were “bad,” but couldn’t seem to control.

I lied compulsively about things that didn’t make sense. I was terrified of being abandoned, to the point that I became furiously, sometimes abusively, upset if I thought that my friends were hanging out without me. I was full of self-loathing and anger that I bottled up, and then released by self-injuring.

I was charming and made friends easily, but friendships never lasted longer than a year or two — and each time one ended, I hated myself so much that I wanted to die.

I did nearly die, twice, of suicide.

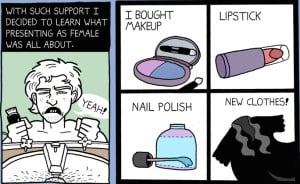

And, of course, I had grown up as a closeted trans girl of color in a cis, white supremacist society. Ever since I could remember, I had been filled with rage and fear and self-loathing as a result of the constant messages that society, friends, and family sent me that said I was deviant, bad, wrong to the core.

A lot of my fellow therapists like to joke that we get into the business primarily to “shrink ourselves.” When I think back, I was definitely searching for myself in that Abnormal Psychology textbook — I wanted answers to the questions that I’d been thinking about since I was at least six years old.

Was there something broken inside me? Could it be fixed?

I found my answer in that textbook — in a sub-chapter labeled, “Personality Disorders, Cluster B.” My “symptoms” fit the profile of a mental disorder called Borderline Personality Disorder, a condition closely associated with psychopathy. It was, the textbook said, historically considered untreatable.

In other words, there was something broken inside me — and no, it couldn’t be fixed.

In the interest of being a responsible mental health professional, I should note here that it’s generally not advisable to try and diagnose yourself using nothing but an undergraduate psychology textbook. Do not try this at home!

Rather, the point I want to focus on here is the experience of living with mental health issues that are “ugly” or social undesirable — disorders like violent psychopathy or paranoid schizophrenia that are generally considered unlikeable, freaky, disgusting, dangerous, or monstrous, even in social circles that consider themselves “progressive” on mental health issues.

I want to focus on the ways in which oppressive social forces such as poverty, racism and systemic violence, as well as personal traumas like child abuse and neglect, are actually responsible for creating and maintaining the symptoms of the most hated and feared mental illnesses.

“Ugly” Illnesses: The Mental Disorders We Don’t Empathize With

Stigma accompanies all mental illness to some extent, but in recent years, certain mental illnesses have been getting better press than others. Depression, for example, has been frequently covered in the mainstream media, from webcomics to feature-length documentaries.

Such news pieces tend to follow the social justice trend of arguing for the destigmatization of mood disorders like depression, arguing against the idea that depressed people are responsible for their experience — rather, depression is caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain.

Yet similar media treatment and public dialogue has rarely been extended to mental illnesses that are not as easy to empathize with. A relatively large number of people, I’d bet, are willing to admit that they empathize with depression because they themselves have felt depressed at some point or other.

I somehow doubt that a similarly large number of people would say that they feel compassion for psychopaths, pathological liars, or narcissists.

In a society enamored with the rhetoric of positive thinking, so-called “toxic people,” like those with the disorders I mentioned above, have become the bogeymen and witches of the mental health conversation — despite the fact that nearly one in ten people in the United States of America are estimated to exhibit traits associated with these conditions.

On the flip side, popular culture is obsessed with caricatured or fetishized representations of violent psychopathy and psychosis, examples of which have appeared in TV and movies for the past century: Dexter, Girl Interrupted, Law and Order: SVU, The Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal, are just the first few titles that spring to mind.

It wouldn’t be politically correct (at least in the left-leaning circles I run in) to say that depressed or anxious people don’t deserve empathy, social support, or friendship.

Yet one of the worst descriptors that even political-correctness social justice warrior diehards choose to bestow on someone is the term “psychopath.”

This attitude extends to mental health professionals as well, where the term “borderline” (personality disorder) is often used as shorthand for “uncooperative patient whom I don’t like.”

As a social worker in a child psychiatry department, I’ve seen professionals describe violently aggressive or manipulative children — some as young as five years old — as “budding psychopaths,” “lost causes,” and “baby murderers.”

The piece that almost always gets lost here is that people aren’t aggressive or manipulative for no reason. There aren’t simply “evil” people who were dropped on Earth with the purpose of harming others. Aggressive or manipulative personalities are most often developed in response to a combination of genetic vulnerability and severe environmental and childhood trauma.

And while violence, emotional manipulation, and abuse are never acceptable, we need to find ways of understanding why people become violent, manipulative and abusive in order to help them stop — because imprisonment and ostracization are only band-aid measures at best.

Social determinants of health — such as access to housing, education, nutrition, parenting, and healthcare — are hugely significant in creating the environments that allow people to mentally develop in pro-social, non-violent ways.

Beneath aggression and manipulation, there is always fear, and often trauma. When we open ourselves to this reality, we become open to the possibility of helping other heal from their trauma, aggression, and manipulation — and to seeing and healing from our own as well.

The following mental illnesses are commonly misunderstood and vilified in society – here’s how to think about them with compassion instead.

1. “Psychopathy,” “Sociopathy,” or Anti-Social Personality Disorder

Perhaps no other psychological concept has caught fire in the public imagination as much as the terms “psychopath” and “sociopath.” In popular usage, these words have become associated with everything from schoolyard bullies to Hollywood supervillains to urban myths about demonic serial killers.

According to the hype, psychopaths/sociopaths are predators, wolves in sheep’s clothing that walk among us undetected, just waiting for the chance to lure unsuspecting people into their devilish games.

Given the enormous amount of media attention given to the concept of the psychopath and sociopath, it may come as something of a surprise that neither clinical psychology nor psychiatry have ever adopted either “psychopathy” or “sociopathy” as a valid diagnostic category.

That right —all of those Hollywood fantasies about psycho killers and crazy ex-girlfriends? They’re based on a fantasy, a cultural construct without roots in actual psychological reality.

The closest actual diagnostic term to the popular idea of psychopathy/sociopathy is antisocial personality disorder, a mental illness characterized by difficulty forming personal relationships, violent and impulsive behavior, and an apparent lack of remorse or caring for others. Individuals diagnosed with antisocial personality are often implicated in the criminal justice and carceral systems — from “small-time” assault offenders to serial killers.

Yet antisocial personality doesn’t occur inside a vacuum. Research shows that personality disorder in adulthood is largely correlated with childhood trauma, abuse, and neglect.

People with antisocial traits respond to the external world with the intensity and violence that matches their internal experience of insecurity — the literal feeling of not being physically safe — which has been ingrained into their psyches.

None of this justifies violent behavior, of course. But it helps us to understand that violence is the symptom of a system that is larger than individual people. Unthinking hatred and rejection of those we deem too aggressive to function in mainstream society is not a good enough answer.

We need to stop relying on psychiatric practices like involuntary commitment and on the prison system to clear society’s conscience of the violence it creates.

We have to find better ways of understanding each other and living together.

2. Borderline Personality Disorder

Another psychological disorder closely associated with the cultural notion of psychopathy is borderline personality disorder. This diagnosis is associated with traits of emotional instability and self-loathing, intense feelings of emptiness and longing for intimacy, manipulation of others, and self-injury.

Common cultural tropes associated with borderline personality include the “crazy ex-girlfriend,” “crazy mother,” and pretty much every “crazy woman” stereotype out there.

Not coincidentally, the overwhelming majority of individuals diagnosed with borderline personality are women — which itself is a sign that there is more going on here than meets the eye.

In mental health professional culture, borderline-diagnosed individuals are generally considered the bane of most clinicians — if a client is challenging, for example, or rude, it’s likely that they’ve been dismissively labeled “a borderline” in a clinical team meeting at some point.

This disdain carries over into popular culture, where borderline individuals are often perceived as being “too needy,” “toxic,” and/or “emotionally manipulative.”

What’s usually not discussed about borderline personality is the fact that it’s hugely correlated with experiences of trauma, particularly sexual abuse, and childhood deprivation.

This is where my inner feminist just has to jump in — could the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder be a sexist way of dismissing women (and other people’s) valid responses to traumatic experiences as being “crazy?”

Certainly this wouldn’t be the first instance of psychiatric discourse being used to prop up the patriarchy’s domination of women’s physical and mental realities — there was a time when women who claimed to have been sexually assaulted by their husbands and fathers were commonly diagnosed as “hysterical.”

And when I think of my own childhood, how my own life experiences have contributed to the person I have become today, it certainly makes sense that I would fit the profile of borderline personality disorder (it’s kind of a wonder that no one ever diagnosed me before I found the label myself).

Because here’s the thing — it makes sense to become a liar when you are taught that your truth is bad, worthless, and will get you hurt.

It makes sense to manipulate others into giving you love when you’ve never been able to get it any other way. It makes sense to hate and harm yourself when no one has bothered to tell you that the bad things that happened to you weren’t always your fault.

Sometimes I wonder, where is the “illness” really — is it the people whose psychological and physical suffering causes them to react with rage, fear, and yes, sometimes violence to the traumatizing effects of an oppressive society?

The people whom we stigmatize, sensationalize, criminalize beyond all hope of receiving appropriate, compassionate mental health care?

Or is it society that is sick?

Is borderline personality a mental “disorder” or just, well, people reacting to the way that anyone would to terrible things? You tell me.

3. Psychosis

In the middle of the 1950s, my grandmother moved from China to a small town in rural Canada. She spoke no English, had no friends and no job, and was cut off from most of her family.

Shortly after arriving, she developed severe psychosis — what is described in psychiatry as a “break from reality” — which stayed with her for the rest of her life.

In her worst moments, she was relentlessly paranoid, impossible to comprehend, and furious at the world.

To this day, the stigma and fear that surround this story continue to haunt my family.So many years later, it remains a fresh, raw wound. In my work as a therapist, I have come to realize that the same aura of shame resonates within many families in which one or more members have experienced psychosis.

Psychosis is generally defined as the experience of hallucination (seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling, or tasting things that aren’t “really there”) and/or delusion (having beliefs that are inconsistent with mainstream understandings of reality, such as the belief that one is God or being contacted by aliens).

A feature of many mental disorders, including schizophrenia, shizophreniform disorder, mania, and others, it is often considered a mark of the severest forms of psychological illness.

Not only is it the kind of “crazy” that is often impossible to conceal, it’s also the kind that is most often socially rejected as frightening, freakish, dangerous, and disgusting.

Psychotic individuals, often misperceived as being abnormally violent by the public and by law enforcement, are actually no more likely to be violent than anyone else. This doesn’t protect them, though, from being disproportionately affected by job and housing discrimination, police brutality, and imprisonment.

It’s not surprising, then, that we don’t often see florid psychosis represented in the same mental health awareness campaigns that champion the destigmatization of depression, anxiety, and other more “common” mental illnesses.

It’s already hard enough to get PR for mental illnesses that make it difficult to feel happy or socialize in groups — it’s next to impossible to garner public sympathy for those that cause people to inhabit alternate realities.

Individuals who experience, or have experienced, psychosis are often written off as “loonies,” “nutjobs,” “basket cases,” and all of the other degrading, pejorative terms for mental illness. I hear this attitude in both casual and professional conversation all the time.

And silently, secretly, I think about my grandmother: A young girl alone, afraid, trapped by poverty, sexism and racism in a foreign country, plagued by horrifying visions and phantom voices. I think about how psychosis is often inherited generationally.

I wonder, how much of her “madness” was caused by the circumstances of her life? By oppression and systemic violence, by the apathy and rejection of those around her?

And I wonder if someday, if I ever have grandchildren, they’ll think of me, their crazy ancestress, with fondness instead of shame.

Loving the Madness

Nothing is simple when it comes to complex mental illness — there are no easy answers, no political slogans, no webcomics or awareness campaigns that can encompass the full and difficult reality of living with a condition that can be terrifying or hurtful to others.

As writer and mother Jade Campbell writes:

“It’s easy to share memes on Facebook say you support mental illnesses, but until you’re there, in the thick of it, you can’t understand what it’s like. Would you accept it if a mental illness incident happened in front of you? Would you feel compassionate, or would you judge?”

Yet the truth is that many of us, and many of those we love, live their lives in fear of their own minds. We live in terror of the idea, the possibility, that we are damaged goods, incapable of brining anything but pain and shame to ourselves and those around us.

I believe that no one “goes crazy” on their own — that we live in a society that is crazy-making in its capacity for trauma, denial, and rejection of its own complicity in the creation of disturbed and violent individuals.

If everyone had access to security and healthcare, if our social systems were more open to diversity of psychological experience and expression, I truly doubt that mental illness as we know it would exist.

This is what we must strive for: a greater understanding of how social oppression and intergenerational trauma breed violence and more trauma. We must come to the realization that everyone exists on a spectrum of mental health and illness, and that no one lives without being affected in some way by the “illness” side of the scale.

We must learn to recognize, and love the madness we find within ourselves so that we might better hold and heal the madness we encounter in the world.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kai Cheng Thom is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Chinese trans woman writer, poet, and performance artist based in Montreal. She also holds a Master’s degree in clinical social work, and is working toward creating accessible, politically conscious mental health care for marginalized youth in her community. You can find out more about her work on her website and at Monster Academy.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more