Source: Unsplash

Up until a few years ago, I had a very specific idea of what rape is.

For the most part, this specific idea was informed by the rape myths that are circulated in a rape culture.

I thought that rape only included vaginal penetration with a penis. I thought it was always physically violent. I thought that if the victim or survivor didn’t say “no,” it wasn’t really rape.

In short, I had a lot of harmful misconceptions about rape.

Society has a tendency to represent only certain narratives around sexual assault. This misrepresentation only adds to the harmful misconceptions we often buy into.

But when my life was touched by a number of queer and feminist activists, I was exposed to a great number of different rape narratives – narratives that weren’t “traditional” or represented in the mainstream.

Not only did it enable me to heal as a victim of rape, but it also enabled me to be more supportive to other people who’ve experienced sexual assault.

What Are Non-Traditional Rape Narratives?

Non-traditional rape narratives are representations of rape that seem unusual, uncommon, or completely impossible.

Traditional rape narratives, on the other hand, are the common stories and experiences we hear about rape and sexual assault.

The problem with traditional rape narratives is not that they’re incorrect or that they never happen. The issue is that they’re incomplete: They show us one experience instead of a range of different experiences.

As a result, we think that non-traditional rape narratives aren’t real, painful, valid, or traumatic. We begin to marginalize a great number of people who’ve had an experience outside of the “norm.”

And that’s not okay.

Some people experience rape in ways that are different to how society represents rape. They deserve to have their experiences acknowledged and validated.

When we marginalize certain experiences around rape, we support the idea that only certain kinds of rape are “real” and deserving of our attention and activism.

And that, my friends, is an extension of rape culture.

With this in mind, let’s look at some of the reasons why non-traditional rape narratives are important.

1. They Challenge Stereotypes of Rape and Survivors/Victims

When we only ever show women as liking clothes, cute animals, and romcoms, we make people think that’s the only way women can be.

When we only ever represent lesbians as butch, society thinks that’s the only way lesbians can be.

And when we only show one kind of rape narrative, society thinks there’s only one way rape can be experienced. We think of survivors and victims of sexual assault as a monolithic group.

Humans are complex. When we oversimplify a group of people, we erase their uniqueness. We erase their humanity.

This is why representation matters in every situation. When we only present one kind of experience – however valid that one experience may be – it might become a harmful stereotype.

Non-traditional rape narratives can challenge those stereotypes and, in doing so, can challenge our one-dimensional views of rape and the people who are harmed by it.

When we realize that there are a number of different ways to experience sexual assault, we remember that those who experience sexual assault are complex.

We all feel differently. We all hurt differently. We all heal differently.

And our diversity of different experiences is what makes us human.

2. They Comfort Others with Non-Traditional Narratives

I was once sexually assaulted by a woman.

Because she was a woman, and because of the circumstances surrounding the rape, my experience was “non-traditional.”

I knew what my perpetrator did was legally and ethically rape, yet I struggled to acknowledge my own pain. Part of the reason for this is that I had no blueprint to show me how to navigate my trauma: I hadn’t heard many stories about people who had been assaulted by women.

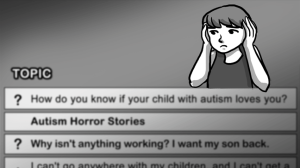

In the news, in fictional works, in the education system, in the legal system, and even in anti-rape communities, we forget to represent those who have been sexually assaulted by people who aren’t men.

I felt like my experience was invalid, and this made it difficult for me to heal.

Struggling to find narratives that were similar to mine, I looked to my old friend – the Internet – to seek out other women who were sexually assaulted by women.

Finding their stories brought me a great deal of comfort and relief. I felt as though I finally found a community where the unique power dynamics of women/women sexual assault were understood. I found people who acknowledged my pain.

I thought to myself, “If their experiences of assault are valid, mine are, too.”

I felt that if they could survive, I could, too.

I felt that if their stories were just as important as others, mine was, too.

And I’m not alone in this. My work with survivors and victims suggests that hearing others’ stories – especially ones that are similar to your own – can be incredibly healing.

Some of us don’t always want to be exposed to stories about abuse and assault – and that’s totally valid. But it’s important that those stories are out there for when we need them.

Representing a number of different, diverse rape narratives can bring immense comfort and healing to those who need it.

If we’re here for all survivors and victims, we need to show them that we care about all of their experiences – not just the experiences that reflect our traditional ideas about rape.

3. They Challenge the Idea That ‘Real Men Don’t Rape’

I love crime shows. They truly are a guilty pleasure of mine.

But often, when rape is represented on these shows, the perpetrators always fit a certain trope.

First of all, they’re always male. Secondly, they’re often unknown to the victims, mentally ill, and from a poor or working-class background.

It’s not just crime shows – even news outlets over-represent rapists who conform to this trope.

There is also the harmful, racist stereotype of black men being particularly sexually unrestrained, violent, and “brutish.”

In other words, the perpetrators of rape are usually represented as the most marginalized men in our society.

They’re never any other gender – nor do they fit our ideas of what a “real man” is.

The idea that “real men don’t rape” is a very common, but deeply harmful idea.

It implies that only a certain kind of man commits the act of rape. As a result, we subconsciously think traditionally masculine men (white, middle-to-upper class, straight, cisgender, attractive men) aren’t capable of rape.

Of course, people can be rapists no matter what their a/gender, gender expression, or sexuality.

But it’s hard to remember that when traditional rape narratives represent rapists as being only a certain type of person.

These stereotypes are harmful because they reinforce a lot of myths around who rapes. These myths are often used against black men, mentally ill people, and gender non-conforming folk.

They also invalidate the experiences of those who were assaulted by “real men” and people who aren’t men. Even as someone who is outspoken about her sexual assaults, I often subconsciously doubt whether my experience of being assaulted by a woman is “real” rape – even though I should know better.

It’s important that we represent non-traditional rape narratives because they can challenge these mainstream, stereotypical representations of rapists.

In doing so, they remind us that anyone is potentially capable of rape.

4. They Show Us That There Are Many Ways to React to Assault – And None Are Wrong

People tend to scrutinize the behavior of people who’ve been sexually assaulted.

If we seem “too” traumatized, we’re dismissed as “crazy” and thus unreliable. If we don’t seem traumatized “enough,” people find it hard to believe that we could have actually been harmed.

If we don’t report our assault, people think we’re lying or protecting our rapists. If we do, we can be examined, scrutinized, and interrogated by law enforcement, our families, and our communities.

You get the picture: Rape culture is full of these contradictory attitudes towards people who’ve experienced assault.

We perpetuate the idea that our responses to assault can deem our trauma valid or invalid. We convey the notion that some reactions to assault are right, and others are wrong – or totally impossible.

But by showing a range of different responses to rape, we show society that no reaction to sexual assault is wrong.

One of my favorite pieces on the topic of rape is “Trigger Warning: Breakfast,” in which the author describes making breakfast for her rapist the day after the assault took place.

After being sexually assaulted at the age of twelve, I signed a birthday card for my rapist, which was given to him by my group of friends. I always felt like it somehow invalidated my rape – that it was such a weird reaction, it meant that I wasn’t a “real” victim.

Indeed, both of these responses to being sexually assaulted are non-traditional narratives. We’re told that “real” victims don’t do things like make their rapists breakfast or wish them a happy birthday, but that’s simply untrue.

Reading about others’ non-traditional experiences of sexual assaults comforted me.

It reminded me that my reaction to the assault didn’t make my assault any less valid, traumatic, or wrong. It also showed me that sometimes, we react to assault differently than how society says we should – and that’s okay.

By representing a number of non-traditional rape narratives, we remind society that there are many different ways to react to rape, and none of them are invalid.

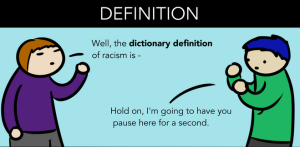

5. They Remind Us of the True Definition of Rape

When we broaden our perception of rape, we can hone in on the definition of rape.

This might seem a bit abstract, so let me explain it.

We know rape myths are incredibly common. Many of us think rape can’t occur between married people, that women can’t commit the act of rape, and that rape is always physically painful – to name a few misconceptions.

The truth is that none of those factors are criteria for defining rape.

Rape is, simply, sexual activity without consent.

It doesn’t require one’s perpetrator to be a stranger. It doesn’t require the survivor to be a virgin or sexually conservative. It doesn’t require the perpetrator to be a man and the survivor to be a woman.

The more we discuss non-traditional rape narratives, the more we emphasize that those “criteria” are actually harmful misconceptions that distract us from the crucial issue of consent.

If we stop asking questions like “What were you wearing? Is he a stranger? Were you drunk? Did you report?” in order to ascertain whether a rape occurred, we can start focusing on questions like, simply, “Was there sexual activity without consent?”

In other words, we focus on the correct meaning of rape – not the oppressive myths that surround sexual assault.

It’s important that we all work towards creating a society where we are all educated on the laws and ethics surrounding rape and consent. This enables sexually active people to be more responsible and ethical themselves.

After all, education is our best tool against ignorance and stigma.

***

We need to call for a change in the way the media represents rape – a way that represents the diversity of rape narratives without implying that one kind of rape is inherently worse than the other.

By understanding and embracing non-traditional rape narratives, we can begin to deconstruct rape culture and move towards a society that values consent and bodily autonomy.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Sian Ferguson is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism and a queer, polyamorous, South African feminist who is currently studying towards a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English and Anthropology. Originally from Cape Town, she now studies at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, where she works as vice-chair of the Gender Action Project. She has been featured as a guest writer on websites such as Women24 and Foxy Box, while also writing for her personal blog. Follow her on Twitter @sianfergs. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more