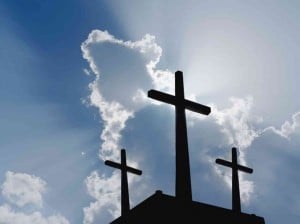

Three crosses in silhouette against a blue sky. Source: NPR

As a kid growing up in a secular Russian-Jewish family in a particularly Christian part of Ohio, I dreaded Christmas.

It was the day all my friends and classmates got dozens of presents from all their family and relatives while I sat at home with no one to hang out with and nowhere to go.

Although my family celebrated our own holidays – Hanukkah, Purim, New Year’s Eve, and others – it was hard not to feel left out of the most wonderful time of the year.

As I got older, I got over my Christmas envy and started to take a lot more pride in my own celebrations, traditions, and rituals. But the experience of growing up as a religious and cultural outsider in my community stuck with me, and now I use it as a lens through which I can understand and analyze Christian privilege.

Like other forms of privilege, Christian privilege is the idea that Christians are afforded unearned benefits in our society that other religious groups and atheists do not receive.

These unearned benefits can be subtle, such as seeing their beliefs portrayed positively in the media, and not-so-subtle, such as being safe from the bullying and violence many non-Christians experience as a result of their beliefs (or lack thereof).

Non-Christians experience marginalization differently depending on their particular identity. Atheists are subject to certain stigmas and prejudices because they do not believe in a deity at all, while Muslims face Islamophobia, which intersects with racism.

Though my own experiences as a Jewish atheist have shaped my understanding of Christian privilege, they are not at all universal.

While examples of Christian privilege abound throughout the year, they can be especially easy to notice during the holiday season.

Here are five ways Christians and Christianity are privileged at this time of year that I’d like to highlight in order to help us understand how we can be more inclusive of people of other or no religions.

1. Christians Are Much More Likely to Have Their Holidays Off Work

Before I get into this, it’s important to note that getting paid time off work at all is a form of class privilege. Many people work jobs that don’t allow or guarantee paid time off for holidays.

Those are the people working long hours to make sure that you get your Black Friday deals and last-minute Christmas turkey from the supermarket, and we shouldn’t leave them out of this discussion.

But those workplaces that do close on holidays tend only to close on the Christian ones.

Christians with class privilege get to spend their holidays with loved ones; the rest of us often don’t, class privilege or not.

2. Christians With Hearing Privilege Encounter Music Celebrating Their Holiday Everywhere They Go This Month

Don’t get me wrong: I love Christmas music. I’m not entirely sure why – maybe it just brings positive memories of winter break and school band concerts and playing in the snow.

For many other non-Christians, though, the prevalence of Christmas music at this time of year is a constant, grating reminder of the fact that our traditions and celebrations remain largely invisible.

You’ll hear plenty of songs about baby Jesus and Santa Claus, but you won’t hear much about ancient wars in Jerusalem or about the seven principles of Kwanzaa.

And, sure, maybe there aren’t nearly as many songs out there about non-Christian holidays (though I’m sure there are more than we realize).

That’s why the ubiquitous Christmas music isn’t necessarily a problem in and of itself, but rather a very visible symptom of the deeper issue: the fact that one particular religion pervades American society so completely.

3. Inclusive Holiday Greetings, Decorations, and Celebrations Are Still Controversial to Many Christians.

Thankfully, we’ve been making a lot of progress as a society when it comes to including non-Christians in winter holiday celebrations and highlighting non-Christian traditions and practices at this time of year.

There are menorahs alongside Christmas trees, Kwanzaa cards in stores along with Christmas cards, and “Happy Holidays” starting to replace “Merry Christmas” as a greeting when we don’t know which particular holiday(s) someone observes.

That’s great, and it makes me happy to see so many changes just in the past few years.

However, the reactions of many Christians, especially politically conservative ones, make it clear that Christian privilege is still very much entrenched.

Each December, right-wing Christian pundits and writers rehash the argument that there’s a “War on Christmas” in the form of secular holiday greetings, inclusive decorations, and insufficiently Christmas-y Starbucks cups.

Like many dominant groups who are slowly losing their privileged status, these Christians see any advance for other groups as an attack on them and their beliefs rather than as a much-needed leveling of the playing field.

But it shouldn’t be “controversial” to say “Happy Holidays” instead of “Merry Christmas,” or to display a menorah alongside a Christmas tree. The fact that it apparently still is shows that Christian privilege, while (hopefully) waning, is still very much a part of our society.

4. People Who Don’t Observe Christian Holidays Often Find Themselves Pitied by Others

What if I told you that I’m thinking of spending Christmas alone, reading a book? To many people, that sounds sad and pathetic.

“But Christmas is about family!” they say. “You can’t be alone on Christmas!”

But what if Christmas for some of us is just another lazy weekend day – What’s so sad about spending it relaxing on our own?

Reflecting on her Christmases spent alone, atheist activist Greta Christina writes:

“I remember in particular one phone conversation I had on one particular Christmas Day. I was doing the rounds of Christmas phone calls, and one of the people I was talking to asked what I was doing that day.

I said that I was just hanging around reading books and eating leftovers. And they said, in a voice filled with horror and shock, ‘Alone?!? You’re not spending Christmas alone, are you?’

Up until that moment, I’d felt fine about spending Christmas alone. I’d felt more than fine about it. I’d felt positive and happy about it. I’d been looking forward to my Christmas day alone almost as much as I’d been looking forward to my Christmas Eve of food and festivity and boisterous social chaos.

But as soon as I heard, ‘You’re not spending Christmas alone, are you?’, I suddenly felt ashamed.

I actually wound up lying, just to stop the horrified sympathy: I told them I was alone at the moment, but had plans to go visit friends later in the day. This person’s concern – and I do think it was genuine, well-meaning concern – about me not being a big sad loser on Christmas… it was exactly the thing that made me feel like a big sad loser.”

To me, spending Christmas alone isn’t sad. Spending Jewish holidays like Rosh Hashana and Hannukah alone kind of is, but I often have to because, as I mentioned above, we don’t get those days off from work.

Nobody ever asks me if I’m sad to spend those days alone.

5. Many Christians Conflate Other Religious Winter Holidays with Christmas and The Christian “Holiday Season.”

As I mentioned, lately, December holidays besides Christmas have been getting more attention: Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Winter Solstice, and others. Overall, this is great and I’m always happy to see more awareness of non-Christian holidays.

However, some of this awareness has included an awkward lumping-in of these holidays together with Christmas in a way that’s inaccurate. I’ve heard Hanukkah referred to as “the Jewish Christmas.”

But it’s not.

There can be no “Jewish Christmas” because there are no Jewish holidays that celebrate the birth of Jesus (or any other supernatural figure).

Hanukkah celebrates the victory of the Maccabees over the Seleucid Empire’s forces, which had tried to prevent Jews from practicing their religion.

Unlike Christmas, Hanukkah is considered a minor holiday by those who celebrate it. By contrast, the Jewish version of the “holiday season” takes place early in the fall and includes Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year), Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), and the days before and between them. Together, this period is known as the High Holy Days.

Conflating holidays like Hanukkah with Christmas not only erases their actual significance for the people who observe them, but also reinforces Christian privilege.

The message people like me get from this is that Christians are only comfortable with acknowledging our holidays if they can be made to resemble their own.

***

When it comes to dismantling Christian privilege, it’s very important not to get caught up slapping on bandaids rather than healing the wounds. Every December, some school or community or workplace gets ridiculed for “banning” the phrase “Merry Christmas” or mandating that Christmas trees be renamed “holiday trees.” While the furor over these isolated actions is often itself a symptom of Christian privilege and tired War-on-Christmas rhetoric, it’s also true that these solutions are not solutions at all.

Although the holiday season makes Christian privilege a little easier to notice, the real problem goes far beyond nativity scenes and Santa Claus. Christian privilege rests on the idea that Christianity is superior to other faiths and to atheism and humanism.

In the United States, it also rests on the idea that this country was set up “for” Christians and not for others, which is an idea that right-wing Christians commonly espouse despite the fact that religious freedom is one of this country’s founding ideals.

As Ellen Friedrichs explains in her article, ending Christian privilege requires Christians to educate themselves about other religions and about atheism and to become more aware of the ways in which they receive unearned advantages that others don’t.

On a larger scale, it requires defending the separation of church and state and targeting all of the oppressions that intersect with and prop up Christian privilege: sexism, racism, homophobia, and others.

And in order for us to be able to do that, this conversation needs to continue long after the presents are unwrapped and the Christmas lights come down, especially in the face of rising Islamophobia in the US.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Miri Mogilevsky is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a recently graduated with a Masters in Social Work and is starting a career as a counselor in Columbus, Ohio. She loves reading, writing, and learning about psychology, social justice, and sexuality, and is working on her cat photography skills. Miri writes a blog called Brute Reason, rants on Tumblr, and occasionally even tweets @sondosia.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more