Source: Unsplash

I’m sick of other people talking about my body.

Whether that’s remarks from my parents about how much my body weighs, advice from my relatives on how to take care of my body, or comments from strangers about how exotic my body looks — my body is mine.

It should be mine to care for, mine to do with what I want, and mine to love.

My right to have that healthy, loving relationship with my body is undermined every day by others who dictate how I should look and feel, what to do with my body, and what to think about my body.

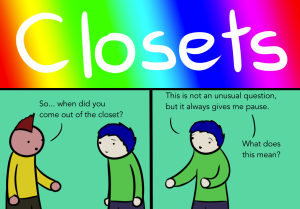

As an East Asian American woman who is also queer, I’m told a lot of things about my body.

What size my body is supposed to be.

Who my body is allowed to fuck (and who it isn’t).

Where my body is supposed to be temporally and spatially.

How my body is supposed to control my feelings.

The ideological tropes around Asian American woman as hyper-heterosexual; as pretty, tiny, and delicate; as good girls and model minorities; as foreign… these all manifest in ways that cut and dig at me internally.

I want to reset the expectations and the boundaries around my body. I want to see changes in how my body is represented. I want to lay claim to all the things I’m allowed do with my body.

I demand a reclamation of my rights to my own body as an Asian American woman.

1. I Have the Right to My Own Personal Space and Having My Boundaries Respected

When I was younger, people would pick me up without my consent. Friends thought I was fun to lift and to throw.

When we are in crowded places, my mom, who is 5 feet tall and petite, often gets physically moved or touched by strangers who are trying to get by or who want to guide her certain directions.

This type of touching is unwanted, patronizing, invasive, and creepy.

I’ve directly experienced this and also heard enough stories from other friends to understand that this type of touching by strangers is commonly experienced by many Asian American women.

Our bodies, no matter their shape and size, are not open and accessible.

This is situated in the larger, darker context of sexual assault and violence in the Asian American community, which often goes unreported.

2. I Have the Right to Access All Forms of Healthcare

I want access to mental healthcare that can understand the specificities of my experiences. The first time I went to a therapist, the woman kept asking me if I felt my parents were strict and controlling.

It was such a reductive way of approaching my needs, and the entire time I felt the need to defend my family from this person.

Simultaneously, in trying to talk to my parents about seeking suitable mental healthcare, they resist therapy as a viable solution – there is a stigma around therapy, that there must be something wrong with someone who needs therapy.

The general perception that Asian Americans don’t struggle with mental health obscures the mental health issues that so many of us face on a daily basis.

In fact, many basic health care needs in the Asian American community go unaddressed, such as the fact that 2 million Asian Americans don’t have insurance. There are often language and cultural barriers to getting quality health care.

There are also damaging cultural assumptions that the medical industry makes about Asian Americans. For example, in relation to reproductive rights, feticide laws target women of color, and in many places, cultural misinformation about the relationship between Asian nations and feticide are at play. In Indiana, the only two women prosecuted for feticide are of Asian descent, even though Asian residents are only 2% of the population.

3. I Have the Right to Better Representation Culturally and Politically

I need to see more people like me in media and politics. Not just people that look like me, but people that can actually speak to the nuances of my experiences.

In both of arenas of media and politics, there is limited representation of Asian American women and their multiple experiences.

There continues to be a dearth of Asian Americans in mainstream media. For example, Asians make up less than 5% of speaking characters in top Hollywood movies.

In terms of politics, even though there are over 18 million Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the US, we are also underrepresented or rendered invisible. Since 1957, there have only been 30 representatives and 7 senators of Asian American descent in Congress. Only 1 Asian American woman has ever been elected to Senate and 9 elected to the House. Just 0.4% of state legislative seats are held by Asian-American women.

I’m not just a fetish or a sidekick. I am not your model minority. I am not a one-dimensional character. I deserve to be seen multi-dimensionally, beyond my “Asian-ness.”

We deserve to be counted. We deserve to be represented. We deserve to have our voices matter publicly and politically.

We are not apolitical or unengaged. Our bodies, our existence is political. We deserve to be counted. We deserve to be represented.

4. I Have the Right to Do What I Want When I Grow Up

One of the worst pieces of television I’ve seen was Anthony Bourdain’s Part’s Unknown episode set in Koreatown. One of the opening lines in the episode was, “For Korean Americans, according to the stereotype anyway, it used to be that you grew up to be a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer… Thanks to some remarkably bad Koreans, though, things are beginning to change.”

This dichotomy of “good” Asian and “bad” Asian, where goodness is reduced to one’s professional status and “badness” is reduced to not going to medical, law, engineering or business school, erases economic needs faced by the Asian American community and obscures the ways that “good” Asians are leveraged against other people of color.

My options of what I do when I grow up and what I do with my time shouldn’t be limited by my race and shouldn’t be morally categorized based on stereotypes about my race.

5. I Have the Right to Eat Whatever I Want

It’s my decision what to put in my body, and this includes food that others think is smelly, stinky, and weird.

This also includes food that others designate as unhealthy, and also how much food I eat. My relationship between food and my shouldn’t dictated by what others think about or want from my body.

My choices of how I sustain myself are not anyone else’s concern but my own. Period.

6. I Have The Right to Dissent.

Asian American women haven’t historically been seen as fierce and powerful, as dissenters, as rebels. People imagine us as compliant, safe, and quiet. We are cute, decorative bodies that signal peaceful multiculturalism.

Our anger, our rage, our frustration does not belong in this imagination. My ability to express all the ugliness of my emotions is trapped and contained by this.

When I share stories, my emotions, and my vulnerabilities about daily injustices around racism and sexism experienced, they are often dismissed as being too sensitive. Too harsh.

My feelings get deprioritized. Now, I’m trained to prioritize the feelings of others, to swallow down my frustrations, to keep peace.

I deserve to have my experiences and feelings validated and I deserve to have my stories take up space.

7. I Have the Right to Know My Own History

My body and my being belongs to an extensive world history that I don’t know enough about. I wish I knew more about ways I am situated and positioned in a larger historical context. My history should be more than just a story about trade for exotic goods, about what my ancestors could offer the West.

I want to hear these from the perspectives of those who inherit the legacy of this history.

Our current educational system whitewashes and sanitizes history. I want to know about the Asian Americans who helped build this country with their bodies and their labor and their joy. I want to know their stories – their pain, their joy.

This country tends to forget its memories of us, but I want to remember.

8. I Have the Right to Belong without Exception

“Where are you really from?” “Go back to China.”

My right to belong to home and to community is often in contention depending on public perceptions of my “Asian-ness.”

Sometimes, my body is perceived as innocuous and safe. Sometimes, it is perceived as out-of-place. Sometimes, it is perceived as a threat.

Asian American women are often seen as “perpetual foreigners.” While this often annoying everyday interactions where people ask invasive questions about immigration status, ethnicity, and national origin, the larger implications of this logic is when State law and policy that continue to treat Asian Americans as foreign.

The US has a long history of exclusionary immigration policy that responds directly to State anxieties over foreign relations. The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II also continues to be a glossed over and forgotten legacy of US.

The State has made it so that we are only allowed to belong sometimes. We can only belong if we abide by the rules, keep our heads down, work hard, and play nice. If we don’t, we are unpatriotic, disloyal, and dangerous.

I have a right to belong without my belonging constantly being questioned and without my belonging as contingent on our country’s international economic and political affairs.

9. I Have the Right to Not Be Exploited

There is the stereotype that Asians are naturally hard workers — and because this hard work is respected, it often isn’t rewarded. This also works hand-in-hand with stereotypes about Asian women as docile and subordinate.

Asian labor is seen as a cheap commodity. We are the cheap labor for building railroads, working farms, sewing clothes and laundering clothes, assembling technology… countries can import Asians as labor or export work to Asia.

Others think our bodies can be bought for less.

No matter where we work, as Asian American women, our labor is not expendable or low-value.

Labor exploitation specifically impacts Asian American women who recently immigrated, and/or undocumented, as well as Asian woman outside of the US in particular geographic regions and of working and lower class backgrounds. For example, 61% of sweatshops are in Asian countries.

10. I Have the Right to Be Loved Unconditionally

By myself, by my partner(s), by my friends, and by my community.

I do not want love that is contingent upon a future or temporal. It should also never be premised on certain racial or gendered expectations.

I deserve love that’s in the present. This love can transform, shift, change, and evolve, but it should never be ‘waiting’ for something to happen.

***

Ultimately, I have the right to my own body, and I am the only one with the right to my body.

One of my friends often says, “Not here for you,” in response to unwanted sexual remarks about her body. For me, this perfectly encapsulates how I feel about my own body – it’s not here for anyone else but me. Even when I consent for someone else to touch my body, my body is still mine and mine only.

No matter how you present your body, how your express yourself with your body, where you go with your body, how you feel about your body at any particular moment… your body is yours.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Rachel Kuo is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a scholar and educator based in New York City. Her professional background is in designing curriculum and also communications strategy for social justice education initiatives. You can follow her on Twitter @rachelkuo.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more