Four dolls stand side-by-side. They appear muscular and “traditionally masculine.”

We need diverse dolls.

That was the message behind toymaker Mattel’s recent decision to give its most iconic product, Barbie, an inclusive makeover – one that would recognize a multiplicity of ethnicities and body types.

Rather than being limited to the impossibly skinny standard of the classic model, children have a number of options, including “petite,” “tall,” and “curvy,” with the latter featuring wider hips and slightly thicker arms. The doll will also be available in seven different skin tones – a la the recent emoji update that expanded the iPhone emoticons from the default white setting.

If Barbie’s creator, Ruth Handler, has said that the doll was intended to show that “[little girls] could be anything [they] wanted to be,” this long-overdue update shows young women you don’t have to be white and thin to imagine yourself in Barbie’s plastic heels.

But while Barbie has gotten a modern update for a new generation of girls, toys marketed to boys continue to lag behind.

As the CBC reports, male Twitter users have wondered where the equivalent changes are for G.I. Joes and Ken dolls, which represent the male physique as cartoonishly ripped and muscular. Many have largely treated the idea of a Dadbod Ken as a joke – a pot-bellied, beer-swilling plastic oaf with poor fashion sense – but they shouldn’t. He’s just the beginning.

The G.I. Joe of today looks very different than he did when the action figure debuted in 1964. When they launched the movable figurine, Hasbro intended the doll’s design to be “realistic,” representing the everyday appearance of the men who served in the military forces.

G.I. Joe was, of course, white and stunningly handsome – with a square jaw and high cheekbones – but the company’s original prototypes “Rocky,” “Skip,” and “Ace” allegedly represented common men doing extraordinary things (so long as you were white).

Fifty years later, there’s nothing ordinary about G.I. Joe. The 2016 model represents the changing expectations of modern masculinity, as well as the pressures we put on today’s young men to conform to an standard of Adonis-like beauty.

The modern G.I. Joe is more akin to the Incredible Hulk than a camouflaged Everyman – so impossibly ripped that he could burst out of his shirt at any moment.

That connection isn’t happenstance: Superheroes like Captain America, Superman, and Thor have likewise become increasingly jacked in recent years. Since Hugh Jackman first played Wolverine in Bryan Singer’s X-Men franchise starter back in 2000, the character’s appearance has changed drastically. The Y2K edition was noticeably slimmer than in 2014’s Days of Future Past, when Wolverine was a walking Men’s Fitness cover. When photos of Ben Affleck’s Batman surfaced online last year, he looked like a professional bodybuilder, not a billionaire CEO.

Often referred to as the “Marvel body,” the increasing association with of unattainably Olympic physiques with manhood can be dangerous for young men – who are going to ever-greater lengths to look like their heroes.

According to a 2012 study published in the Pediatrics journal, 38 percent of the middle- and high-schoolers surveyed were using protein powders and supplements to bulk up. Six percent even confessed to taking steroids to reach their ideal muscle mass.

These statistics correlate with increasing rates of eating disorders among boys. Although estimates suggest that 1 in 10 of those who suffer from a history of disordered eating is male, these statistics are likely underreported: Like the middle schoolers from the Pediatrics study, many of these men don’t want to be skinnier, they want to be bigger.

Two years ago, Harvard researcher Allison Field and her team found that nearly one in five adolescent males were unhappy with their weight – with half of those respondents expressing a fear that they were too thin.

These boys learn from an early age that to be muscular is not only to be strong but to be desirable and respected amongst your peers. In a word association test, a 2015 study from Staffordshire University study found that young men were most likely to link being fit with “feelings of confidence and power in social situations.” Meanwhile, society continues to associate Ken’s hypothetical #Dadbod as a weakness or personal failing – and even a punchline.

What having the diverse dolls movement can do is normalize a plurality of body types among young men by creating G.I. Joes and Ken dolls that reflect more than one type of masculinity. The danger here isn’t just what’s been called “the tyranny of buffness,” it’s the problem with representing a single story: the experiences of everyone else gets erased and devalued.

When it comes to girls’ toys, a number of brands – in addition to Mattel – are already helping to fill that gap. Makies, a UK-based toy company, recently introduced 3D-printed dolls that came equipped with walking sticks and wheelchairs, in order to give children with disabilities toys that represented their lived experiences. Others had hearing aids, visible birthmarks, or guide dogs.

These accessories proved wildly popular with children and their parents: Sales reports indicate that the manufacturer pushed 70,000 units just in the first week alone.

Makies proved that inclusivity is big business, and if Mattel hopes that its diverse Barbies will help fight flagging sales in recent years, little boys should have toys that do the same.

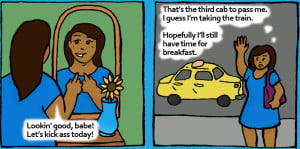

Today, black or Asian Ken dolls remain a rarity – illustrating a very narrow view of the kinds of men that are seen as potential romantic interests for the young women who play with them. Why can’t a hearing-impaired Ken lounge at the Barbie mansion, too? Where’s Stacey’s Pakistani dreamboat?

Hasbro likewise needs a wake-up call when it comes to the action figures it makes for young men. If Ruth Handler suggested that dolls and action figures are meant to offer attainable possibility models to which to aspire, a single white, muscular, straight, cisgender, able-bodied ideal simply isn’t enough.

For companies that allegedly inspire kids to dream, it’s clear that toys for boys continue to lack imagination.

***

To read more from The Daily Dot, check out:

- When mom is lonely: The Tinder for parent friends

- How the furry community rallied when Zarafa Giraffe lost his head

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Nico Lang is a Meryl Streep enthusiast, critic, and essayist. You can read his work on Salon, Rolling Stone, and the Guardian. He’s also the author of “The Young People Who Traverse Dimensions” and the co-editor of the bestselling BOYS anthology series. Follow him on Twitter @Nico_Lang.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more