Content Warnings: Mentions of weight loss (including a reference to vomiting)

A person runs their fingers through their hair with one hand, and the other holds a phone which they stare at with annoyance.

Even when we try our best to be sensitive, our words can cause more harm than good.

Personally, I’m all too familiar with the feeling of putting my foot in my mouth, and I’m constantly trying to learn how to make my words as inclusive as possible. Sometimes though, the only way that can happen is if we’re honest about how certain language is damaging.

One thing that has taught me a lot about sensitivity is my experience with Crohn’s Disease; I was officially diagnosed ten years ago, but I experienced the symptoms for much longer. It took a long time, and many misdiagnoses, before my own gastroenterologist would even consider it as an option – partly because some of my symptoms mimicked those that accompany a condition like endometriosis, which I also have.

Crohn’s Disease, a chronic inflammatory condition, is incurable and often progressive. Symptoms can include significant weight loss, severe abdominal pain that doesn’t go away, vomiting, mineral and vitamin deficiencies due to chronic inflammation of the small intestine, ulcers, fistulas, and abscesses. It can cause inflammation that is extra-intestinal: bone density loss, skin lesions and rashes, and joint and ocular problems are all possible manifestations of the disease.

But being that many of the manifestations of Crohn’s are invisible, it can be difficult to understand the scope of the disease. Being unaware, however, only accounts for so much.

Here are some things you should never say to someone with Crohn’s Disease.

1. ‘But You Look So Good!’

I understand not knowing what to say when someone you care about is sick, and it makes sense to grab for something nice to say about that person when you’re at a loss.

You want to give them a compliment to make up for their obvious suffering, or because you have no idea what else to say. I’ve done this before – and I’m sure I’ll do it again – but sometimes those compliments can be harmful.

Women with Crohn’s Disease have been found in a recent study to have a lower self-image than men with the same disease, and while the relationship is unclear, it doesn’t help that our society places such importance on beauty.

When I worked in the salon industry, I was taken aside by every manager I worked under at some point, to be told either gently or bluntly that I needed to step up my cosmetic game.

Even though I always look for ways to buck convention and societal expectations, I couldn’t ignore how scary my extremely pale skin and malnourished frame looked under the ghastly fluorescent lighting tailored to hair salons, so I gave in.

As it was pointed out to me, I was working in a job where appearance mattered, and mine was starting to frighten clients. With a few swipes of bronzer and mascara, clients voiced their concerns less frequently, and the amount of prying questions died down. After some time, it became habit to apply more makeup when I felt worse, creating a thin layer between me and the outside world.

I’ve seen first-hand how something as innocuous as mascara can undermine a woman’s health: Doctors stop asking me how I’m managing my intractable pain, employers don’t believe I’m in the ER, and friends stop asking me to social functions because they think I’m a flake.

Cosmetics have the ability to disguise many things; with studies showing how much of an impact makeup can have on the public’s perception, it only makes sense that women with Crohn’s Disease or other invisible illnesses feel extra pressure to use it as a shield from the truth.

Aside from cosmetics, society places an obvious importance on weight – and those of us with Crohn’s Disease often deal with severe weight fluctuation.

Over the last decade, I’ve had every primary doctor and specialist equate my rapid weight loss as a positive, because I looked better thin in their opinion. When I last saw my gynecologist, he couldn’t stop ruminating over my significant loss in a few months, insisting I must be doing something different.

The truth? “I’ve been vomiting a lot more.”

Our society perpetuates the bigotry of fatphobia when they assume thinner bodies to be healthier ones. Instead of taking note of my rapid weight loss or gain, instead of taking a look into what is really going on internally, the healthcare industry makes us feel our suffering is more psychosomatic than anything else.

While you may be trying to offer a compliment, a person’s appearance shouldn’t be commented on, and it certainly shouldn’t be a measure of health.

2. ‘Such-and-Such Diet Will Cure You’

If I had a dollar for every time someone told me that a cleanse or diet would eradicate my Crohn’s, I would have a lot of dollars.

My last boss regaled me with the numerous ways that a cleanse, followed by a special, expensive liquid diet (which he happened to be selling) cured others with serious autoimmune diseases. He made it known on a daily basis that he thought I could be doing more about my condition, without asking about my prior history, so I retreated into my earbuds and let my music tune out his oblivious claims.

Cleanses, “clean eating,” and other popular diets may provide invaluable results for some people, but to suggest food will cure an incurable disease insinuates that we don’t look for alternatives, that we aren’t trying hard enough to treat our symptoms.

Not only can certain foods – some of them main staples of popular diet programs – trigger symptoms to the point of hospitalization, but many of us can’t afford the extra cost of designer organic produce, or we live in a food desert that makes dietary variety inaccessible.

In “My Body Doesn’t Need a Cure: Sizeism, Classism, and the Big Business Hustle of Clean-Eating,” Laura Bogart says: “Our culture has always found ways to problematize poor people and fat people, often conflating the two groups in the terrible stereotypes of the Pepsi-swilling welfare queen, and the Cheetos-munching, Nascar-loving boogeyman who willfully inflates healthcare costs for everyone with his abominable laziness.”

Unfortunately, I’ve become so accustomed to uninvited commentary about food, I’m a bit desensitized. But I still get slightly offended when someone who knows nothing about my medical history offers unsolicited advice.

This discomfort plays a big part in why I don’t eat in public most of the time. Aside from not knowing from one minute to the next what my body will do if I consume something my digestive tract deems foreign, I can’t enjoy my meal without worrying someone will judge.

The irony for me is that just before I was officially diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease, I was eating healthier than ever, with a high-fiber diet and regular exercise. My first instructions after the extended hospital stay was to avoid all of my favorite foods, and replace them with bland, flavorless alternatives. Years later, after trial and error, I’ve found what works for my digestive system, and what doesn’t; each of us with this disease react differently to medications or diet restrictions.

When I surveyed a group of people with Crohn’s Disease about some of the most damaging things said, the suggestion for a new diet was among the most common. One responder, Judy Walters, finds that people want to suggest certain diets as a treatment for Crohn’s, despite the fact that our bodies each react differently: “Crohn’s can’t be controlled by diet, though some people with Crohn’s find avoiding some foods helpful. Crohn’s is an autoimmune disease that affects the entire digestive system.”

Being that Crohn’s symptoms aren’t only limited to the digestive tract, it erases the life-threatening conditions that can accompany the disease when someone suggests that any of it is curable with food.

3. ‘You’re So Lucky’

Before I learned the hard way to listen to my body, I worked a minimum of fifty hours a week, often more than one job. Over the years, my health trials made me redefine my relationship to money. From the day I was able to start earning, I put financial autonomy ahead of all other goals – being codependent never factored into the equation.

Since being diagnosed, I’ve been reminded of my “luck” quite frequently: When I balked at missing weeks of (unpaid) work for a surgery, my doctor told me I was lucky to have a husband who could “pick up the slack,” not taking into account what those weeks cost in the long run.

I’ve been told by co-workers and acquaintances that I’m lucky to be able to lose so much weight so quickly, never mind the always-bloated abdomen and malabsorption of nutrition. But what I get told more than anything is how lucky I am to have a partner who will make money when I cannot.

While I’ve been able to reconcile my relationship to money, and have found what I believe to be a true partnership, I can’t help but feel guilty for being a burden of some kind. So when my inability to earn like before is pointed out, I try to hide my irritation, but it is one of the more sensitive topics those with invisible illnesses encounter.

People with invisible illnesses often deal with financial insecurity: between higher healthcare costs and missing work due to symptom flares, money is always an issue, even if we don’t acknowledge it. Those with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in particular tend to have problems obtaining private insurance, and if they do qualify, the premiums are often unaffordable.

One of the first things my doctors said to me after my diagnosis was, “You’ll never qualify for life insurance again.”

Even when we did get insurance through employers, the monthly amount was always over $400 for two people, and the deductible was so high we paid for most everything out of pocket. Being involved in clinical trials, missing days of work due to illness, and paying astronomical amounts for medication, my insurance coverage meant nothing when I was making very little money.

Money issues aren’t the only cause for anxiety attacks, but they can certainly attribute to it. People with IBD have been found to have greater instances of anxiety and depression following a hospitalization or surgery; to be made to feel like a burden to someone else only increases the likelihood.

For me, a person who has held financial independence as an important ideal for most of my life, having to rely on someone else is a humbling experience. I thank my lucky stars every day that I have a supportive partner, but we support each other, and it is far from one-sided.

4. ‘You Should Try Meditation – It’s Mind Over Matter’

I’ve tried many different types of meditation. And while I can certainly see how it can be beneficial, it’s not a cure for intractable pain.

The practice of mindfulness can actually cause chronic pain to amplify, because focusing on the area of discomfort can make it worse, and for some people, the act of being still isn’t possible.

When we say things like “mind over matter,” we add to the narrative that women have been fighting for centuries – that pain is psychosomatic. In a study titled “The Girl Who Cried Pain,” it was found that women are prescribed pain medication less frequently, even though they experience more severe pain, and doctors are more likely to attribute their pain to being in their minds.

Crohn’s Disease is considered an invisible disability, because it can cause debilitating pain and other symptoms that make it difficult to complete daily tasks or social activities. With inspiration porn being plentiful online, the pressure to conquer your physical limitations – to be stronger than the suffering – is pretty immense. But as Karrie Higgins puts it so succinctly in “Dear Abled Friends: I Am Not Your Inspiration”:

“There is literally nothing physically or mentally I can do to make those symptoms go away, so I can inspire you all with my incredible achievements. But I guess—you know—I have no ‘excuse’ because someone else out there with another disability overcame and achieved ‘in spite’ of everything.”

Comparing one person’s health to another’s is one of the main reasons many of us go so long untreated or being misdiagnosed. When I was younger, I kept quiet about a lot of symptoms, because I was afraid of sounding whiny.

My parents told me time and again that it was mind over matter, and they blamed my pain on my inability to change the focus. They, of course, changed their opinions once they each experienced real pain later in life.

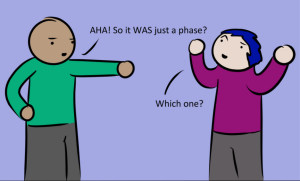

5. ‘You’re Using It as an Excuse’

Like many invisible illnesses, Crohn’s Disease can be very unpredictable, so I understand the confusion at times. One day, I may appear fine; the next, I may not be able to face the public.

I’ve had friends accuse me of being a flake purposely, and bosses insinuate that hospital stays were an attempt at some time off. I can understand how frustrating it can be on the other end, especially when you have no reference point to comprehend the other person’s suffering, but it felt like a slap in the face when co-workers were allowed to leave at any time to take care of their children, no questions asked.

It took me a really long time to be able to talk about my health problems, and part of that reason is because I didn’t want to be viewed as weak.

I was also afraid of missing opportunities, both professionally and socially, if I was honest about what I was going through. It wasn’t an unfounded fear, either – over the years, I’ve lost jobs because of my condition, and have ended a few friendships over people not believing me. Once I open up and tell you what’s going on, I’m putting myself out there, so when someone accuses me of creating the situation, I have very little patience.

When we tell you that we’re unsure if we can make plans, it’s not because we’re looking for something better to do. And if we decline your home cooked food, it isn’t personal, it’s preventative. I know it can seem suspicious when you see us in photos looking relatively well, or if we’re typing up a storm on messenger, but can’t make it to the mailbox. But believe me when I tell you, when we are hiding out, it is for good reason.

If there’s an alternative, we’ve more than likely tried it, and if there is a cure, we sure as hell know about it. When you make someone feel like they are making excuses, it becomes increasingly more difficult to continue the conversation.

***

Many of us are uncomfortable discussing the realities of our disease – there are aspects I’m not sure I’ll ever write about – but the more we talk about it, the easier it becomes to adjust our language.

We live in a society that gives us filters, cropping software, and other tools to make us appear a certain way, so who can fault you for assuming otherwise? It isn’t until we join the ranks of the chronically ill do we realize how our otherwise good-intentions can actually drain an individual, both emotionally and physically.

This applies to all marginalized groups, but if we don’t force ourselves to learn, the oppressive language will only continue.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Diana-Ashley Krach is a full-time freelance writer, author, and journalist whose work can be found on XOJane, Lumen, HelloGiggles, Playboy, Cosmopolitan, DAME, SheKnows, and more. In addition to her personal writing, she has over five years’ experience managing content creation and marketing for companies, covering a wide scope of industries and professions.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more