Two people standing outdoors and smiling, looking at a smartphone with a pink cover together.

I always felt assured that the rise of the Internet and digital publishing could only mean more spaces for marginalized voices, not fewer. The Internet is the place where we can share our narratives, because there aren’t the same privileged gatekeepers and decision makers that exist in traditional media.

When queer women needed to carve out a space by us, for us, we created AfterEllen. Now, after fourteen years, AfterEllen no longer exists the way it used to. It doesn’t have an editorial staff, and those in charge of its parent company are mainly heterosexual men.

As the LGBTQIA+ community becomes more intertwined into the larger mainstream media, there are more and more spaces for queer women to create, to publish, to read, and to be heard.

But there are also fewer spaces that are just by and for us – spaces that offer a unique perspective that always uses the lens of the queer woman’s experience to look at pop culture, social justice issues, politics, sports, fashion, and everything else.

The fact is that media by and for queer women (like any other marginalized identity) is crucial. Not only does it ensure a safe space and a sense of community around our shared experiences, but it also allows space for more diversity and exploration of intersectional identities.

If a larger, mainstream publication chooses to feature queer women’s voices, they may need only a handful of stories, or a few regular contributors. But sites like Autostraddle, because of its sole dedication to queer women, are able to offer more intersectional voices – like from the experiences of QTWOC and disabled queer women.

It’s an issue of representation: The more there is, the more well-rounded and inclusive that representation can be.

Queer women’s media, like AfterEllen, can’t exist without us. Whether you’re a supportive ally to the LGBTQIA+ community, or a queer woman yourself, it’s important that as much as we can, we support queer women’s media and those that create it.

So here are six ways you can support queer women’s media so that it continues to thrive.

1. As a Consumer, Support Marginalized Content with Your Money

Because we live in a capitalist economy, if we enjoy something, we need to support it with our money.

Most content – even online – offers options for consumers to offer monetary support. The main problem with online content is that it’s generally been free. As such, users aren’t used to having to pay to access a website or an online magazine. So they want it for free.

But if you’re consuming a lot of content created by and for queer women or another marginalized group, one way to show your support is by backing it with money – if and when and however that might be feasible for you.

Many sites, like Black Girl Dangerous, will allow you to donate, either on a one-off basis or regularly, or to pay for a subscription, which may offer access to extra content or other perks. Curve Magazine, for example, has a physical magazine that you can subscribe to in addition to their free content online.

Some queer women’s media sites also have an online store, like Autostraddle’s store, or offer affiliate links to purchase from third-party stores with a percent of the profit supporting the site.

Queer women’s media, especially if its content is primarily online, may also offer in-person events – like Autostraddle’s A-Camp, which you can pay to sign up for. (A-Camp also offers scholarships for queer women who wouldn’t be able to otherwise attend.)

At the very least, turn your ad-blockers off while visiting these sites, if possible. If these sites are relying on any advertising revenue, keeping your ads blocked isn’t supporting them.

2. If You Can’t Offer Monetary Support, Use Your Social Influence

Not everyone can support queer women’s media using their purchasing power. I grew up with very little money, and I was lucky enough to have Internet access most of the time, along with a library card. When I actually wanted to buy a book or a magazine, I had to make a conscious decision about what I was supporting and how much money I was spending.

Money isn’t the only way consumers can support queer women’s media, though. Talking about it, whether in-person or online, is another way.

Share the content that you’re enjoying in a way that’s safe for you to do so. If you can’t share on Twitter, for example, because you have a public profile and you live in an area where workplace discrimination is legal, then you might share in a safe LGBTQIA+ forum where new members are looking for resources.

By sharing marginalized content, we’re not only opening the creators up to a larger potential audience and more views, but we’re also introducing them to new consumers who may be bringing in more ad revenue, or who may choose to donate or purchase a subscription or a product.

Now that I’m living in a more stable financial situation, I’ll sometimes choose to donate to crowd-funding campaigns that I believe in, or to purchase products or make donations to creators that I believe in. Where do I find these causes? Often, I find them because someone in my social network shared it and made me aware.

Comment on the work that you’re enjoying. E-mail the creators or the site and let them know how much the work meant to you, or tell them on social media. You have no idea how far a small compliment can go in boosting staff morale. Tell your friends and anyone who you think might appreciate the work, if you’re safe to do so.

Because the more people that know about queer women’s media, the better chance that media has of surviving – and thriving.

3. If You Have the Capacity to Hire Marginalized People, Prioritize That

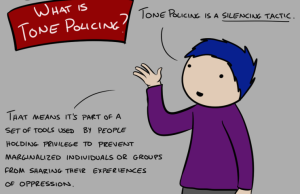

Even in online spaces, where we may think there aren’t as many privileged gatekeepers as there are in traditional media, there can still be barriers to access.

Most media sites have internal staff, such as editors, staff writers, publicists, social media managers, and event coordinators. It’s problematic when sites want to be inclusive in their portrayals of diverse groups, but they don’t have a diverse and inclusive staff.

Because of systemic oppression, it’s traditionally difficult for queer women to break into the media – especially if they have intersecting identities that add another layer of discrimination into the mix.

It’s competitive out there, especially in the media and publishing industries, and queer women (and other marginalized groups) are at an automatic disadvantage. If you have the opportunity to hire queer women, do it – especially those who have multiple intersecting marginalizations.

And please, check your internal bias and privilege if something is telling you that it may be difficult to hire more marginalized people. Because often, the problems we think we see (“Does this person have enough education?”) can be tied back to systemic oppression.

Especially if your staff is going to be writing, editing, managing, acquiring, or decision making about diverse content, it’s even more crucial that you have staff members from marginalized groups who can work with it.

4. If You See Something Harmful, Say Something

As an editor and a writer, I’ve had the capacity to reject or accept submissions and to request edits. There have been several times that I’ve really liked a piece I’ve read, but I felt that it had problematic undertones, such as sex-shaming in a feminist essay. In those moments, I’ve had to make a decision about what to do.

Whether you’re a consumer, a creator, or a gatekeeper and internal staff member, you have the opportunity to say something when you see something problematic. There are situations where your words can really make a change.

As a writer, I was once assigned a piece about “lesbian bed death,” and what queer women do when they experience this. This was for an LGBTQIA+ vertical on a mainstream site. I took it as an opportunity to make sure the piece addressed the fact that “lesbian bed death” is a problematic trope – not a guaranteed experience for all queer women – and then made the focus of the service piece inclusive. I interviewed a diverse selection of queer women, and included information about enthusiastic consent as well.

Similarly, we can choose to speak up when we see that a piece isn’t created with a marginalized group in mind, such as if a white writer creates a work about black women’s experiences.

We can ask the sites we support to allow marginalized communities to speak for themselves and to have members of that community on staff.

5. Hold Yourself Accountable

We all have to accept that, even if we’re marginalized ourselves and consider ourselves purposeful, active allies, we aren’t perfect – and we will make mistakes.

Even if you’re working for a site that publishes a lot of great, inclusive content, you should always hold yourself accountable.

Read through the work you’re publishing and ask yourself if you see any problematic tropes, or if the communities you’re talking about are represented fairly. Having queer women on staff as editors and sensitivity readers is one way to do this for queer women’s content. But if you’re publishing something on intersecting identities, make sure you’re representing that experience authentically and fairly. And the best way to do that is to make sure that the piece is written by a person who has that experience.

After Kylie Jenner posed with a wheelchair for Interview magazine, I was tasked with writing a think piece/op-ed on why this is such a problem. I’m physically disabled, but I’m not a wheelchair user. It was crucial that I centered the voices of wheelchairs users in my piece – that I read their opinions and find out how this had affected them personally.

I asked several colleagues who are wheelchair users to read through my piece and let me know what they thought of it, and we talked about whether it made them uncomfortable to have a non-wheelchair user representing the topic.

After the piece was published, a wheelchair user commented on it, upset that someone outside the community had written it. In this instance, I took the time to reflect on my own privilege and bias, to apologize, and to reconsider how I might write as an ally in the future.

It can be tough to see our own issues, and we’re all raised in a society that enforces systemic oppression and internal biases.

That’s why it’s even more important to constantly challenge ourselves to learn, to read more on marginalized experiences we don’t share (written by those people), to listen to voices and experiences outside our own, and to continuously check our privileges.

6. Amplify Marginalized Voices

After the Pulse shooting, everyone was talking about queer media, representation, and violence. Many of my straight friends were sharing solidarity and talking about what had happened.

That’s extremely important. We need to all consciously think about whose voices we’re amplifying. Are we only sharing privileged voices of professors who have never experienced mental health issues when we talk about content warnings in the classroom? Are we sharing white perspectives on the Black Lives Matter movement?

This comes back to my earlier point about sharing queer women’s content when we can’t support it monetarily. When we share content by marginalized voices, we’re essentially saying to our entire social networks, “Look at this. This is important and worthy of your attention.”

If you consume great media by queer women and other marginalized people, lift them up. Amplify their voices.

If you’re writing on a topic that isn’t part of your own experience, make it clear that you’re writing to other allies about allyship. And that’s a perfect opportunity to link to another person’s original work and encourage readers to go read it.

When I’ve written on the experiences of wheelchair users in the past, I’ve embedded tweets from wheelchair users and linked to essays written by wheelchair users that sum up the experience in a way that I – as someone who doesn’t use one – never could.

Sometimes, especially if you’re in the media or publishing or journalism industry, you might find yourself in a position where you’re asked to write on an experience that isn’t your own.

The most responsible thing to do in this situation is to talk to your supervisor about why this is harmful, and let them know that you think the piece should be written by someone who holds that identity or has that lived experience. If you can suggest a writer for the piece, you’re more likely to get the okay from your editor.

But already, whenever possible, you should also be advocating for the hiring of marginalized people on staff, and use your position of power to recommend multiply marginalized creators for hire.

***

It’s easy enough to say that we support diversity in media and publishing, and to say that we want more inclusive voices. But we all need to do the work to make this happen.

The end of AfterEllen as we knew it is proof that the Internet’s accessibility doesn’t automatically equal more spaces by and for queer women. It’s up to us to show our support for those spaces so that they continue to exist, survive, and thrive.

I was still in middle school when I first found AfterEllen. I was brand new to the queer women’s community. I had no queer friends, and I was coming out – and into my own – for the first time. That space, because it was focused on our experiences, by us and for us, was crucial to me accepting and understanding myself.

And now it’s gone.

In its last year existing, I finally had the opportunity to have two essays published on the site, and it was incredibly gratifying to see my work displayed on a website that I’d pored over as a young teenager. But I also barely read AfterEllen anymore. I definitely didn’t donate money to the site. I shared the occasional article, and I contacted several of their writers to quote in my stories for mainstream publications on queer women’s topics, but what more could I have done?

I felt somewhat at fault when AfterEllen died. I took for granted the fact that it would always exist, that it would always be there when, say, something like the Pulse shooting happened and I needed a safe haven to return to.

I recognize now that just because something is online doesn’t mean it exists permanently. Real people who did this as either their full-time or part-time job, supplemented by people like me who submitted one-off pieces as freelancers, were the ones who ran AfterEllen.

Those people need money to survive.

Queer women need their work supported in order to continuing producing it. And they need our steadfast support to keep doing this important work.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Alaina Leary is a Bostonian currently studying for her MA in publishing at Emerson College. She’s a disabled, queer activist and is on the social media team at We Need Diverse Books. She can often be found re-reading her favorite books and covering everything in glitter. You can find her at www.alainaleary.com or on Instagram and Twitter @alainaskeys.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more