A person with long hair points and laughs at the viewer.

This presidential election brought out a lot of hate from Americans. And I’m not only talking about conservatives.

I’ve heard liberals and conservatives alike talk about how uneducated the other side is, how “old” and out of touch they are, how “crazy” certain politicians are, and even how unattractive they are.

And I get it. When you’re working toward social justice, your priority isn’t to protect people who are already privileged.

But here’s the thing: When we use oppressive rhetoric against people in power, we tacitly condone its use against them and against more marginalized people.

Here are some ways I’ve noticed people further oppression when they try to combat it – and why there’s no room for them in any social justice movement.

1. Mocking the Oppressive Person’s Lack of Education

Since I’m a frequent target of anti-feminist Internet trolls, my friends and other supportive people will often remind me how wrong those trolls are. And I appreciate that a lot. But sometimes, even though it’s very tempting to join in, their criticisms are problematic.

“He can’t even spell,” some will say. Others point out that they have no idea what they’re talking about, citing a job primarily involving manual labor or an ostensible lack of college education.

The problem is, these are often the same people who believe in listening to the voices of people who lack access to education or jobs that are considered prestigious. And you can’t be against classism only when you agree with the person whose class puts them at a disadvantage.

Classism often comes up in critiques of American conservative values, with the redneck stereotype of southern farmers invoked.

The problem with discrediting people’s ideas due to their lack of formal education or their job is that it encourages us to ignore people who are disadvantaged in society, which only serves to keep oppressed people oppressed.

And particularly when spelling and grammar are criticized, we are privileging one upper-class, predominantly white form of English above others, which perpetuates race and class oppression.

We can say somebody has no idea what they’re talking about without attributing their lack of knowledge to their class.

2. Body-Shaming People We Disagree With

Remember that Trump statue that went up in NYC?

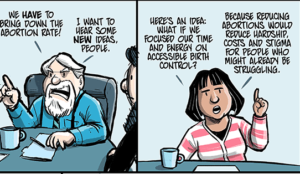

A lot of progressives thought it was funny to humiliate Trump by depicting his body as conventionally unattractive and implying he had a small penis after he suggested otherwise. Political cartoons that are critical of Trump almost always exaggerate his and his supporters’ size.

The problem is that, as with classism, we can’t be against body-shaming only when we like the people being body-shamed.

Was Trump’s talking about his penis size wrong on many levels? Yes. Do we have reason to depict him negatively? Of course.

However, criticizing him by depicting him as fat contributes to the view that being fat is bad. And giving him a small penis contributes to the view that large penises are superior and men should be stereotypically masculine.

Mocking micropenises is a form of violence against certain intersex people, transgender people, and other marginalized people who sometimes have them. The quip “He must just be overcompensating for a small penis” may be typically directed toward cis men, but it brings less privileged groups down with them.

You often hear people criticize the looks of their political or ideological opponents, and that’s just as ugly when it comes from the left as it is when it comes from the right.

3. Sex-Shaming Women We Disagree With

Speaking of bad reasons to criticize Trump, that scandal over Melania’s GQ photoshoot is another prime example.

As Zeba Blay points out in The Huffington Post, some people were contrasting her with the “classy” Michelle Obama. “They went from a Harvard graduate to a stripper,” someone tweeted (also invoking classism) after Trump won the election.

This feeds right into the virgin-whore dichotomy: Michelle dresses conservatively and is therefore “good”; Melania poses provocatively and is therefore “bad.”

If we really want to stand up for women and progressive values, we should be challenging the idea that what a woman does or doesn’t wear says something important about her, not comparing women based on how sexual they appear.

Posing nude for a photoshoot doesn’t set women back, but focusing on a woman’s looks or sexuality rather than what political skills she’ll contribute as First Lady does.

4. Using Ableist Language

When I get verbally attacked by men’s rights activists, people often defend me by calling them “crazy” or “sensitive.” And, as with the criticism of trolls’ grammar, I enjoy feeling supported and almost want to go along with it. But I can’t – because I’ve been called “crazy” and “sensitive” myself.

“Crazy” is used to dismiss someone’s ideas by implying that they have a mental illness. This actively harms people with actual mental illnesses by implying that their condition makes them less credible.

It’s also very common to call politicians with extreme views “crazy,” which not only stigmatizes mental illness but also masks the fact that they’re worse than “crazy.”

“For a long time, the left has had two caricatures of conservatives: that we are either stupid or evil. I take it as a backhanded compliment that they have, to some extent, invented a third category for me: ‘crazy,’” Ted Cruz wrote in his book.

The word “crazy” trivializes the gravity of oppressive policies like Cruz’s and masks their link to structural oppression. And “stupid,” another word often thrown around to describe uninformed political agendas, is also ableist because it implies that people with low IQs should have less of a say in politics.

And then there’s “sensitive.” People often say this about groups like MRAs and Republicans to imply that they’re overly concerned with people who are already privileged. That’s definitely an issue, but “sensitive” is not the right word to describe it.

That is, after all, the same word people use to imply that feminists are upset about gender inequality simply because they’re overly emotional or psychologically damaged.

It also feeds into the stereotype that people who are passionate about a cause have a mental illness. But being passion and emotion aren’t the problem. The problem is being invested in the wrong cause.

Let’s call out that problem, rather than attacking someone for supposedly having poor mental health or a disability.

5. Using People’s Age as a Reason to Dismiss Them

“Our problem is that old men have been running our country.”

“Don’t listen to that grandma.”

I’ve heard many comments like these, which equate progressiveness with youth, from people in social justice circles.

And it is true that different generations view certain issues differently on average. For example, younger people appear a bit more open to LGBTQIA+ rights. And it is certainly important for young people to have representation.

But older people are also disenfranchised in many ways, and criticizing their age is a careless, harmful shortcut used to criticize backwards views.

After Trump’s election, I saw a comment on a discouraged-sounding Facebook post reassuring the poster than soon, the old white men who voted him into office will die out, and more progressive young people will have more control over the government.

While there is a grain of truth to this – more Millennials voted for Clinton than older generations – 37% of Millennials still voted for Trump; and moreover, saying that the world will be a better place once a group of people dies is insulting to that group of people.

There are plenty of older people who have been fighting for equality, and saying that their cohort is the reason we’re in an a bad situation contributes to the stereotype that they’re all behind the times.

***

Sexism, classism, racism, ableism, and all the other -isms that go into these misguided methods of combating oppression are so pervasive that people end up using them even as they’re criticizing them.

It just goes to show that none of us are immune to these ways of thinking, and it’s necessary to constantly ask ourselves if we’re unintentionally buying into them.

I know how hard it can be to defend your own Twitter trolls against classist remarks or defend politicians you despise against ableist accusations. But you can’t be halfway in the fight for equality. Combatting oppression is pretty binary: Either you oppose it in all cases or you’re enabling it.

Because every time we fat-shame Donald Trump or sex-shame Melania, we contribute to a world that allows the shaming of less-privileged people. And that’s not a world I want to live in.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Suzannah Weiss is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a New York-based writer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Salon, Seventeen, Buzzfeed, The Huffington Post, Bustle, and more. She holds degrees in Gender and Sexuality Studies, Modern Culture and Media, and Cognitive Neuroscience from Brown University. You can follow her on Twitter @suzannahweiss.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more