Young child standing in front of a tattered house with bags and other objects scattered on the porch and the front yard. Another young child is walking into the house.

I’ll never forget the girl in my college sociology class who thought it was the easiest thing in the world.

In a seminar about class, we went around the room to describe which income echelon we thought our families were in.

“Middle class,” said most kids.

“I guess upper-middle class?” asked a girl in Coach sneakers.

“Ah, well… Low-income,” I stated. I was the only one.

Then, our professor asked us each to explain how we thought people end up in the social class they’re in. Coach Sneakers wasn’t hesitant this time: “Because some people work hard, and some people don’t.”

The American Dream is built on the notion that anyone can get ahead – that monetary security, financial comfort, and even the occasional vacation or luxury item are all within reach to any and all citizens.

Holding up this vision is a deeply-rooted belief (which goes back to decades-old ideals of “Social Darwinism” and is often reinforced by our upbringing and education, not to mention the political views of a lot of, um, “leaders”) that the equation for success is quite simple: If we work hard, we will get ahead.

In this framework, the solution to poverty is neatly tied up in a bow made of our own individual bootstraps.

Unfortunately, this is based on one giant, huge, incorrect assumption that the playing field is perfectly leveled – that we live in a society and an economic system that rewards hard work equally.

You probably know that race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, and any other number of identities may change a person’s starting position in the race toward financial and social stability.

But you may not always be able to see the different ways that economic status does, too.

Basically, socioeconomic status exists on an intersectional continuum like so many social systems – and when talking and thinking about poverty, we need to treat it as such.

This is especially crucial for those of us with an interest and investment in social justice. Like many other systemic forms of oppression, the trials and outcomes of people who experience poverty (particularly during childhood) can be invisible and extremely hard to parse out and understand if you haven’t experienced them first-hand.

There are a variety of emotional, physical, and even neurological disadvantages that come along with childhood poverty. Pointing them out and examining their impacts can help us begin to redraw the starting line and dismantle the narrative that poverty can be escaped by climbing harder.

So here are some facts to help you recognize the challenges of escaping poverty.

1. Poverty Is a Complex Cycle of Factors

One of the most important aspects of conceptualizing how poverty impacts people is to understand that it is more than just not having money.

We often think of poverty as monetary status – someone doesn’t have money right now; thus, they are poor – rather than a cycle.

Put more simply, poor people are just like not-poor people, except they have less money right now. But chronic poverty (the kind that impacts families and entire communities) is not the same as being broke, and it’s not the same as being low on funds before your parents deposit your rent money.

What defines poverty isn’t just the fact that someone’s bank account is overdrawn. Poverty is not a temporary status for most individuals and families.

Instead, it’s a cycle that continues to self-perpetuate and worsen over time.

Not everyone who lives in poverty is born poor. Plenty of people experience injuries, changes in their industry, death, divorce, mental illness, chronic illness, medical bills, and any other number of all-too-common bank-breakers that decrease their earnings significantly.

But once you’ve become poor in the US, you tend to stay there and raise your children there. And if you’re born poor, there’s only a 30% chance that you’ll ascend to the middle class (and this number drops significantly depending on your ethnicity).

In fact, one of the biggest indicators of a child’s success isn’t how hard they work as an adult, but how much money their parents made. And upper- and middle-class kids, regardless of their grades or performance, are more likely to make it out of college with a degree than those from low-income families.

That’s because the trappings of systemic poverty are woven into the fabric of daily life, particularly for individuals and families who live in economically depressed areas, whether starting from a young age or not.

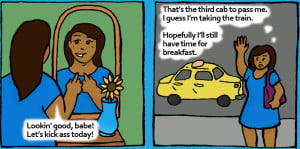

Adults who have recently found themselves living in poverty often struggle with myriad hurdles – like access to transportation and healthcare – which makes it difficult to get on their feet again.

But for those who are born into poor households, the deck is really stacked.

Small (but crucial) pieces of legacy poverty begin impacting a child from day one and create a foundation that is difficult to dismantle as they get older – particularly if they never got the tools to do so.

Here are just a few of the ways that children living in poverty are set back from those in the middle-class when they attempt to better their financial status:

- Access to good schools and instruction

- Access to nutrition, both early in life and as an adult

- Access to future-planning assistance (how do you apply for college if no one in your family has ever done it?)

- Access to internships and other jobs that require time, but don’t pay enough to pay rent

- Career opportunities through parental or familial connections (like alumni networks)

- Access to social safety nets (like parents who can help pay a bill or two)

Lack of access, on multiple fronts, all add up to an uphill battle to increase a person’s lifetime earnings.

There are also very real physical and psychological barriers created or worsened by childhood poverty. Childhood poverty has been found to actually alter brain chemistry and function.

One 2015 study found that up to 20% of the achievement gap between low-income and middle-income children could be attributed to reduced brain surface.

Low-income individuals and families also suffer from interacting with a financial system that penalizes them and profits off of poverty.

Overdraft fees, payday lenders, and student debt all disproportionately impact low-income folks, making it difficult to save money, make necessary purchases without incurring huge penalties, and require the single, biggest action we tell people to take to get ahead: Go to college.

2. Poverty Is an Intersectional Issue

Often, poverty and income inequality (like other topics in the economic sphere) are set aside from “social” issues (like feminism, systemic racism, immigration, criminal justice reform, and the difficulties of the LGBTQIA+ community).

This is a problem because it creates a siloing effect, both in how we view poverty and income inequality and in how to best help those experiencing these issues.

We don’t often look at the ways that poverty intersects with the issues of marginalized groups, and instead, tend to treat it as a separate ailment.

In reality, poverty is caused by much more than just a lack of jobs or expensive housing. For many communities, poverty is a byproduct of other systemic issues.

Mass incarceration is a poverty contributor. Mass deportations are a poverty contributor. And of course, systematic racial and ethnic income gaps in the workplace contribute to poverty.

Everyone has heard the “77 cents to the dollar” figure about the gender wage gap, and perhaps many even know that it’s much larger for Black and Brown folks. But few realize that documented wage gaps also exist for folks who are LGBTQIA+, Native American, new Americans, and disabled, just to name a handful.

Most children will never experience poverty. Approximately one in five children lives below the poverty line, though as many as 40% may be considered “low-income,” based on the cost of living.

However, unsurprisingly, those numbers don’t tell the full story, which is that poverty hits some communities much harder than others.

And though poverty cuts across identities, it demonstrably impacts some identities much more than others.

Black and Latinx kids are more likely to live in poverty than their white peers – and while the number of white children living in poverty has dipped in recent years, the number of children of color has remained steady.

Additionally, Black adults who escape poverty are more likely to backslide at some point in their lives, in large part due to the other oppressions that plague historically Black neighborhoods.

By continuing to divide poverty from other identity intersections, we’re permitted to ignore the very real economic consequences of a legacy of racism, misogyny, ableism, anti-queer and -trans discrimination, and so much more.

3. Stereotypes About How to Get Out of Poverty Have Real Consequences

Unfortunately, despite mountains of evidence (not to mention the lived experience of millions of Americans), you may still have a hard time shaking the idea that the only thing standing between poor people and wealthy people is how hard they’ve worked and how much they wanted to succeed.

And that’s unfortunately very common.

Even more unfortunately, this belief – when held by voters and reinforced by lawmakers eager to please their constituents – has led to troubling and even dangerous policies that perpetuate the cycle of poverty.

For example, a huge portion of the funds from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program – what we typically think of as “welfare” – go toward so-called “welfare to work” programs.

These programs directly tie assistance money to job attainment and retention, and have been demonstrably shown time and again to be ineffective at helping people escape poverty.

Additionally, House Speaker Paul Ryan has doubled down on these programs in his proposal, entitled “A Better Way,” despite numerous reports that the method is ineffective.

These programs are hugely popular policies with lawmakers and voters because they sound like the kind of programs that we have been told works. They appear to make poor people responsible for their choices and force them to get back on their feet.

However, these programs don’t take into account the challenges of economically distressed areas, nor do they tackle systemic wage gaps, skills gaps, or issues like debt, housing costs, and financial literacy.

Instead, they often leave people trapped in a cycle of poverty with no escape – and then blame them for it.

Stereotypes about poverty are also frequently value judgements about poor people, which are also not based in reality.

Many Americans believe that the bulk of assistance dollars goes to poor people who squander them. This is untrue. The majority of welfare dollars go to other programs that have little to no empirical evidence to support their efficacy.

Since the 1996 welfare reform package, though, people are getting less assistance than they used to – despite evidence which shows that direct cash assistance is one of the most effective uses of public dollars.

There’s also a distinct element of racism in how people view those living in poverty and receiving assistance – whether it’s “welfare queens” or “Obama phones,” many white Americans incorrectly assume that people of color make up the bulk of welfare recipients.

That’s also untrue. The majority of food stamp recipients are white.

However, by upholding this racist belief, lawmakers are able to continue to deprive communities of color of what they need while catering to white voters.

***

By perpetuating these stereotypes and failing to address the real, root problems which contribute to poverty, citizens telegraph to lawmakers that ineffective, harmful policies are what will get them reelected, and that they are not interested in tackling issues of marginalization in their communities or the country at large.

However, plenty of people don’t realize how deeply they hold these beliefs, or how much these beliefs inform their understanding of the economy.

We tend to believe these ideas implicitly and without criticism – often, because it feels safer to do so.

After all, if hard work doesn’t relate directly to success, what does that mean for our own path toward success?

But acknowledging that wealth – or even financial stability – is a privilege doesn’t mean that those with means haven’t also worked hard.

Benefitting from largely invisible forces – like parents with college degrees or attending well-funded public schools – doesn’t mean people don’t have to work as hard or that their work means less.

But it does mean that their work tends to go farther and that they’re permitted to fail or stumble without catastrophic outcomes.

Hard work is an important component for success – but it’s certainly not a guaranteed road out of poverty.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Hanna Brooks Olsen is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism, a small human, and a Millennial. Her interests are politics, podcasts, Pac-12 football, feminism, and Oxford commas. She is curious to a fault. Follow her on Twitter @mshannabrooks.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more