A group of college graduates in their caps and gowns hold a sign that says, “Hire me!”

Growing up, I remember folks saying that low income people “just needed to get an education” in order to get better-paying jobs, move up in the economy, and survive.

I was raised by a disabled, low-income, single mom in a neighborhood filled with other low-income people – mainly people of color, people with disabilities, and immigrants. Although my mom is the holder of a B.S. and had previously worked in medicine and biology, we were poor.

She’d been disabled her entire life, but the symptoms of some of her disabilities worsened with age, leaving her to choose between working full-time or raising me with the help of disability benefits.

As a child, I was surrounded by low-income people, both those who held college degrees and those who didn’t. And although I never quite believed the myth that poor people just need to go to college for their financial situations to change, it was still a myth that persisted in my life until I was a high school senior applying to college.

My dad – who is also disabled, but not a college graduate – had chosen not to attend Northeastern University in his twenties because his blue-collar parents discouraged him from doing so. He’d worked in everything from printing presses to universities to transportation to personal care assistance, but he always regretted that he didn’t get a college education.

Although he meant well, he helped feed me the myth that a college education was the key to my problems – the solution to not being poor like my parents for the rest of my life.

My dad didn’t want me to count my change to pay bills or need to apply for government assistance, which can be a time-consuming and emotionally draining process.

I was privileged in that I am not technically a first-generation college student. Although my mom had passed away by the time I was applying and my dad was the one assisting me, I had a healthy amount of family support.

My parents had been together when my mom was getting her degree. My mom’s entire side of the family was filled with college graduates; a few went on to get master’s degrees or go to law school. My older cousin Nicole had gone to college and was able to explain a lot of the process to my dad, fortunately, and when he couldn’t get up-to-date answers from her or another family member, he did his own research.

The main point, according to him, was this: I was going to graduate from college and get my master’s degree afterward. This was the most financially and emotionally successful way for me to attain success, and it was what he pushed me toward.

Now I’m the holder of a bachelor’s degree and will earn my master’s in May. Along the way, I’ve learned a lot more about the myths surrounding poverty – and how to get get out of it – that exist, and how these myths are harmful to low-income people.

Here are just a few of the reasons that the “poor people just need to get an education” myth doesn’t work.

1. The College Application Process May Not Be Accessible to Low-Income Students

When I was applying to college, it was my dad who told me it was possible to apply for waivers for the SATs and for the college application fees.

With fees ranging from $60-150 per school, I needed those waivers to afford to apply to a wide range of schools so I could make informed decisions about which college to attend.

Many of my other low-income friends weren’t aware of the waivers, and wound up paying out of pocket for SATs. When I found out they had saved waitressing money to pay for the test and couldn’t afford to retake it for the chance at a higher score, I told them what I knew about how to get a waiver.

My high school guidance counselor never sat students down to tell them about these options. Even though I went to a fairly small school, she was too busy to individually assess student’s problems and help them with the application process. My dad had to fight her just to get information on exactly how many waivers I was eligible for, and what other options existed for low-income students.

The application process can require a lot of time and money that low-income families simply don’t have.

In high school, I didn’t have a car, so I had to carpool with friends to take the SATs and base my test schedule around when they were going. I couldn’t afford an $800 SAT prep course at the local community college, so I studied from borrowed library books and online.

If I’d gotten to the interview stage at an Ivy League college, I don’t know how I would’ve gotten transportation to attend the interview. When I had to print out application materials, I used my high school library and asked friends to help, because I didn’t have the money for a home printer.

I was fortunate that I had friends and family who were able to guide me through the process, to explain to me how I could cut costs during the application process.

Despite the waivers, we still ended up spending over $200 on the applications, which on bad months could be the difference between paying a bill or not.

2. They May Be Unaware of What Financial Aid Is Available for College

The most nerve-wracking part of the application process was knowing that, in the end, the effort would be wasted if I didn’t get into a school with all my costs covered.

My dad couldn’t afford to pay out of pocket for any expenses, not even to give just $1000 to the college each semester. The money simply did not exist.

My top-choice college, which I got into, offered me the fullest financial aid package – mostly made up of grants and scholarships that didn’t need to be paid back. I was thrilled!

The problem was, despite aid covering most of the cost of attendance, there was still about $10,000 that I needed to cover for my freshman year.

When I called the college financial aid representatives, they were only able to offer me a few more thousand dollars, and couldn’t cover the costs completely.

Because I was just turning eighteen at the time, I had no credit and didn’t even qualify for personal loans. I couldn’t use my dad as a co-signer because of his poor credit from a history of trying, and failing, to pay bills on time, which is a fairly common reason for low-income families to have low credit scores.

I had to base my college decision on financial aid just as much – if not more – than which school I wanted to attend or felt was the best fit for my career.

In the end, I chose a public state university. They were able not only to cover my cost of attendance, but also offer me money every semester for books and out-of-pocket costs such as food and transportation.

And with textbooks racking up to $500 a semester in costs, I knew this was the only affordable option – I had to take it.

My dad and I still had to find a way to pull together $200 for the housing deposit by May first, but by putting off some less important bills and eating cheap fast food for a month, we managed it.

There are many low-income families who struggle to even raise this amount of money, and we were told by the college financial aid that there were no waivers or aid for low-income students who couldn’t afford the housing deposit.

Low-income students may also not know how to file the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or apply for private scholarships, grants, and loans if they don’t have other family members who recently attended college.

The cost of attendance wasn’t as high, and securing aid wasn’t as complicated during our parents’ generation, so even if low-income students have an older relative who went to college, they may not be able to help.

I knew how to file FAFSA because my cousin Nicole explained it to us, and the online system was fairly easy to use. My dad and I did run into some genuine trouble applying my first year, because he wasn’t aware that the Social Security benefits he received to take care of me because my mom had passed away were supposed to be filed as a source of income.

It wasn’t until he got on the phone with a FAFSA representative that we finally filed correctly and were told that we had an estimated family contribution of $0 per year.

That, at least, felt accurate, and I was weirdly grateful that the system recognized how little money we had to put toward my education.

3. There May Not Be Enough Continued Support for Them to Thrive

Before I started my undergraduate career, I thought getting in and securing financial aid was the hard part and that everything else would “just take care of itself.”

I was completely wrong. For low-income students, it can be hard to get past the first semester, never mind making it to graduation.

I was academically prepared to keep up because my parents had worked hard throughout my life to get me the best education that (free) public schools could offer. This was a privilege for me, and was difficult for them.

We couldn’t afford to move to get me into a better school district, but my mom helped me get school-sanctioned, free tutors as a kid, and my dad got me into the honors program at the best public middle school in our city.

He worked as a cab driver when I lived with him, so he’d pick me up during his work hours to bring me (or we’d take the bus together) to after-school programs in writing, science, and the arts.

In high school, I participated in free opportunities, like taking an internship at the local veterinary clinic and taking college-level classes at the community college.

Socially and financially, however, I struggled. As a low-income student, it can be hard to fit in or feel equal to your peers.

Most of my college supplies were secondhand. I couldn’t afford a mini fridge or a microwave, so my roommate had to supply them.

We didn’t have a car, so I was constantly asking friends for rides to and from campus. My notebooks were from the dollar store, and my decorations were homemade art that I’d made in my free time.

Institutional support for low-income students also varies wildly. At my public university, I somehow didn’t qualify for work study, despite my family’s low income.

I began applying for on-campus jobs the first week of freshman year, but I was turned down for positions like delivering mail to other dorms. I’d go back to my room and cry, knowing I really needed that $10/hour.

There was a campus program for low-income student support, but in order to qualify, you had to be a first-generation student as well as low-income.

Low-income students also often have to think about things like:

Will I continue to get the same amount of financial aid every year? What happens if I’m offered less aid? Will I be able to finish my degree in four years, and if I can’t, can I get financial aid for the final year or semester?

Will I be provided housing, or will I have to move off campus eventually? How affordable is the area my college is in? Will things like housing, food, and entertainment be particularly expensive where I live?

My sophomore year onward, I received more and more financial aid annually as my university offered me more, based on merit. I finished my freshman year with a 4.0 GPA, and each semester, the grants left me with actual spending money, allowing me the “luxury” of things like going off campus, supplying my half of the shared apartment supplies, and buying my friends holiday presents.

I was lucky that we had on-campus housing all four years guaranteed, and my university gave me a scholarship to cover the cost of food when I lived in an on-campus apartment my senior year and needed to cook.

I still stressed for months about affording my share of apartment essentials like pots and pans, but I was fortunate enough to get a paid summer internship that allowed me to pay for those items.

A big reason I was able to afford college and graduate on time was because I had friends and family who helped me out when they could, or I simply got lucky. A lot of it wasn’t due to institutional support for low-income students.

One semester, I wasn’t able to get a grant to cover my textbooks, and my girlfriend had to loan me the money to rent them. Another year, a friend and his mom helped me move out of my dorm room. When I got a flat tire, a friend let me use his AAA Roadside Assistance because I couldn’t afford a membership.

My roommate took me out to dinner for the holidays, and friends gave me rides to and from college until my junior year, when I inherited a very used car from my late grandmother.

4. Unpaid Internships Are Particularly Harmful to Low-Income Students

Working for free already sucks if you have plenty of money, and it sucks even more if you don’t – that is, if you can even afford to handle an unpaid internship at all.

Unpaid work disproportionately affects low-income students because we’re already the most economically vulnerable. We feel pressure to take on these work-for-free opportunities because we need experience along with our education to get a “good job,” but we also often literally can’t afford to take them.

The only reason I was able to take three unpaid internships during college was because my university offered a scholarship stipend to those who did, and the schedules were flexible enough that I could still work on-campus part time.

Through the scholarship, I ended up making around $15-17 an hour on my internships, which is not the same as working for free. During the summer, I was in no position to take on an unpaid internship even though I wanted to, because I needed income, and it left me only able to apply to summer jobs and paid internships.

Unpaid internships are also an intersectional problem.

Low income students more likely tend to be people of color, children of immigrants, first generation college students, or people with disabilities – people who are already marginalized out of too many opportunities.

I had to turn down great opportunities to work for free in Boston during my college summers, even though I really needed valuable experience and contacts in my field, because it simply wasn’t feasible for me to pay for gas, car repairs, car insurance, my cell phone bill, and to save up for the next year of college without making any money.

What’s worse is that many summer internships are full-time, meaning interns work forty hours a week and aren’t left with much time to make money through a part-time job or freelance work.

5. College Isn’t the Solution for Everyone

People also frequently forget that college isn’t the solution for everyone, and it isn’t a one-size-fits-all experience.

There are many jobs that require a bachelor’s degree that really shouldn’t, because most of the work is learned on the job anyway. There are also plenty of trade opportunities and industries that don’t require a bachelor’s degree (or more) for entry.

And we often don’t talk about the simple fact that low-income students can go to college, graduate, and still struggle to find jobs – and on top of that, they may be in debt from their college experience.

The cost of college is extremely high, and research has found that many colleges actually give more financial aid to wealthier students, leaving low-income students to endure disproportionately more economic hardship.

I also think of my mom, who graduated from college but wasn’t able to keep a full-time job because of her disability.

I’m disabled too, and I know how hard it can be for people with disabilities to get a job, whether it’s because of employment discrimination or a lack of accessible workplaces.

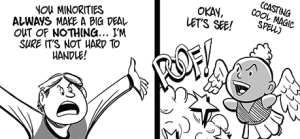

If you graduate from college and you’re a low-income student – especially if you’re multiply marginalized – a cycle of subtle discrimination can keep you struggling to find work or be paid fairly.

People of color, especially women of color, are paid less than their equally qualified counterparts for the same work. LGBTQIA+ people (especially those who are transgender) face employment discrimination that may be so hidden that it’s impossible to legally fight, as well as elevated unemployment rates.

When we talk about the diversity in academia and many college education-required industries, we have to talk about these barriers. Because they seriously limit low-income people, especially those who are multiply marginalized.

***

In 2015, I finished my bachelor’s degree. It was a stressful experience, especially financially – every semester worrying, How will I get to college next year? Will I have enough financial aid to make it through my remaining years? How will I explain to my roommates if I can’t chip in for my part of our dorm essentials?

Even as I was close to graduating, the cycle continued again because I’d applied for master’s degree programs.

This time, the stress felt very timely. My dad suffered a serious traumatic brain injury in a car accident a couple years ago, and I knew he wouldn’t be able to take care of me under his roof for much longer with his health conditions and economic situation. I knew I couldn’t rely on him for a permanent place to live after graduating from college.

The hardest part, sometimes, is the idea that because you’ve got higher education, you’re supposed to be successful and economically thriving. But that often just isn’t the case.

You can graduate from college in a timely manner, take several internships, even get a master’s or other graduate degree, and still struggle to find a paying job, or any job at all.

I was always under the impression that the higher education you had, the easier it was to find work – and well-paying, economically stable work, at that. Unfortunately, that isn’t true, and many people with PhDs are on food stamps and other government benefits because they’re underpaid and underemployed.

The “poor people just need an education” myth as a function of classism works for many reasons.

For one, it places the responsibility on low-income people to “fix their situation” or “better themselves,” instead of on the systemic oppression that keeps people trapped in a cycle of poverty – especially if they’re multiply marginalized.

It also works alongside the bootstraps myth to make people feel as though all their successes are a direct result of hard work and education, and allows them to ignore their own privilege, which in turn allows them to ignore the oppression of others.

It’s a lot easier to believe that poor people can just easily apply to college, get in, graduate, and have all their problems solved than it is to deal with the difficult reality of underemployment, discrimination, systemic oppression, rising student debt, unpaid internships, and underpaid employees.

But all diversity outreach initiatives need to have this myth, and everything that comes with it, in mind.

Because college isn’t the answer for everyone– and even those who want to attend often struggle with the process for reasons out of their control.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Alaina Leary is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Bostonian currently studying for her MA in publishing at Emerson College. She’s a disabled, queer activist and is on the social media team at We Need Diverse Books. She can often be found re-reading her favorite books and covering everything in glitter. You can find her at www.alainaleary.com or on Instagram and Twitter @alainaskeys.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more